In my last post, Selfie Sabotage, I reported that Dylan seemed anxious about people taking photographs by camera or mobile phone. This is now written into Dylan’s care plan so he is no longer exposed to photography at the care home or while he is with me. Although this has involved a change in practice, I have found it surprisingly easy to put my phone away while I’m with Dylan. Last week I took Dylan to Marske-by-the-Sea for his summer holiday. As well as spending time on the beach we visited places I would previously have photographed but which I didn’t even consider getting my camera out for. It’s reassuring to me that habits can be quickly and painlessly changed when necessary.

In my last post, Selfie Sabotage, I reported that Dylan seemed anxious about people taking photographs by camera or mobile phone. This is now written into Dylan’s care plan so he is no longer exposed to photography at the care home or while he is with me. Although this has involved a change in practice, I have found it surprisingly easy to put my phone away while I’m with Dylan. Last week I took Dylan to Marske-by-the-Sea for his summer holiday. As well as spending time on the beach we visited places I would previously have photographed but which I didn’t even consider getting my camera out for. It’s reassuring to me that habits can be quickly and painlessly changed when necessary.

My impression is that the ban on photographs has made Dylan more comfortable and I’m pleased I spotted that this was an issue for him. Something that struck me last week, however, is that anxiety about photographs could, in time, be replaced by something else. Because I wasn’t able to take photographs, I made written notes about our trips and the places we visited instead. By the end of the week Dylan was shouting ‘pen, pen’ at me every time I got my notebook out.

Turkle and Technology

I was minded of Dylan’s phone-phobia recently while reading a Jonathan Franzen essay on Sherry Turkle (a ‘technology skeptic who was once a believer’). Children, Turkle writes, ‘can’t get their parents’ attention away from their phones’. The decline in interaction within a family, Turkle suggests, inflicts social, emotional and psychological damage on children, specifically ‘the development of trust and self-esteem’ and ‘the capacity for empathy, friendship and intimacy’. Parents need to ‘step up to their responsibilities as mentors’, Turkle argues, and practice the patient art of conversation with their children rather than demonstrating parental love (as Franzen puts it) ‘by snapping lots of pictures and posting them on Facebook’.

I was minded of Dylan’s phone-phobia recently while reading a Jonathan Franzen essay on Sherry Turkle (a ‘technology skeptic who was once a believer’). Children, Turkle writes, ‘can’t get their parents’ attention away from their phones’. The decline in interaction within a family, Turkle suggests, inflicts social, emotional and psychological damage on children, specifically ‘the development of trust and self-esteem’ and ‘the capacity for empathy, friendship and intimacy’. Parents need to ‘step up to their responsibilities as mentors’, Turkle argues, and practice the patient art of conversation with their children rather than demonstrating parental love (as Franzen puts it) ‘by snapping lots of pictures and posting them on Facebook’.

Turkle’s points about the impact of technology on child development could perhaps also apply to Dylan. If patience is a necessary quality when engaging a child in conversation, this is even more the case when communicating with someone who is non-verbal. Although Dylan is an adult in terms of chronological age, cognitively he is around five years of age (according to best attempts to assess this). Certainly, I would identify the development of empathy, trust and self-esteem as relevant to his nurturing and care.

If there is any chance at all that exposing Dylan to technology could be limiting his opportunities for development then of course I should follow Turkle’s advice. But perhaps Dylan intuitively knows this? His protests about my phone were maybe because he wants my undivided attention – in which case, having to wait while I write in my notebook might be just as irritating to him as waiting for me to take a photo. Reading Franzen’s essay brought to mind another technology-related issue that I’ve had to deal with in relation to Dylan’s care recently. Rather than Dylan being the one protesting about the technology (as with phones and cameras) however, in this instance I have been the one doing the sabotaging.

Dylan’s iPad

Dylan has been using an iPad for years, primarily to access CDs and films he has purchased and downloaded and which he can watch offline. Previously, Dylan had portable DVD and CD players for this purpose but the iPad proved a better option practically and for promoting independence. Although initially intended for use during journeys and holidays, Dylan became increasingly attached to his iPad and built it into his daily routine, often preferring it to his TV or over other activities.

Dylan has been using an iPad for years, primarily to access CDs and films he has purchased and downloaded and which he can watch offline. Previously, Dylan had portable DVD and CD players for this purpose but the iPad proved a better option practically and for promoting independence. Although initially intended for use during journeys and holidays, Dylan became increasingly attached to his iPad and built it into his daily routine, often preferring it to his TV or over other activities.

Recently, however, a problem emerged. On a number of occasions, Dylan managed to ‘lose’ the music he had purchased. This happened every three months or so, always while Dylan was at his care home. Staff didn’t notice Dylan’s music had disappeared but they did report ‘challenging incidents’ for which there was ‘no apparent trigger’. Dylan would, however, show me that his music was missing when he came on a home visit and I would then have to set about fixing the problem. This was more complicated than Dylan merely ‘hiding’ the purchases (for which there are retrieval instructions) and required Apple technicians recovering the music so that it could be re-downloaded to Dylan’s iPad. The technicians were always professional, efficient and impressively competent but the process was time-consuming and frustrating.

After the third fix, I asked if care home staff could provide more support to Dylan while he was using his iPad and suggested that they check it regularly, particularly if Dylan seemed frustrated or upset. When Dylan presented me with the problem again, just a week later, I decided a different solution was required. Fair enough to fix something once or twice, but Dylan’s iPad seemed to have become a source of stress rather than a resource. How had this problem developed and why was it happening more regularly? I checked the stats to see how long Dylan had been spending on his iPad. Quietly aghast, I opened my secret drawer – the one where Dylan doesn’t know to look – and slipped the iPad inside.

Intellectual Disability and Technology

It is very hard to remove something from an adult, even when they lack the capacity to make decisions and need someone to act in their best interests. Dylan had been using an iPad for years and it had a key role in his life. I was aware that in removing it I could create more problems than I solved. The iPad, however, was itself the source of some of the difficulties which Dylan was encountering.

It is very hard to remove something from an adult, even when they lack the capacity to make decisions and need someone to act in their best interests. Dylan had been using an iPad for years and it had a key role in his life. I was aware that in removing it I could create more problems than I solved. The iPad, however, was itself the source of some of the difficulties which Dylan was encountering.

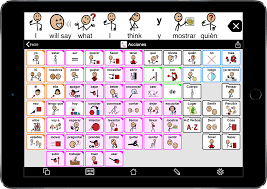

Tech companies do not have intellectually disabled adults at the forefront of their mind during research and design and, as consequence, even the most intuitive apps and products are not always accessible, particularly to those adults who do not use speech to communicate (i.e. who are not literate and who cannot process spoken language). Although there are some great pre-school and pre-linguistic resources on the market, Intellectually disabled adults are not pre-linguistic children, they are adults who do not (and probably are not going to develop) spoken and/or written language.

Like the school curriculum, technology is language-based and thus inaccessible to people who do not use language to communicate. It is sometimes possible to adjust a setting on a device so that it uses visual information. For example, Dylan is perfectly able to choose between the album covers of his music downloads. Apple’s default setting, however, is to display his music alphabetically, by artist/CD name. Dylan cannot read the text so he has no idea where to click. If his iPad defaulted to the text-based rather than visual setting (which it did, with every upgrade) Dylan would become disoriented and distressed.

This has always been an issue for Dylan, but the problem seems to have become more acute since January when Apple rolled out a major upgrade to their music streaming service. Of course, what Apple want is for people to use their Music streaming service rather than purchase albums as Dylan does. However, Dylan is not able to use the streaming service because it is language-based. He needs his pre-purchased music, visually displayed. When it isn’t available to him in accessible format, Dylan tends to press keys and click icons and hit whatever message (language-based, which he can’t read) appears on the screen. I assume that it is at these times that Dylan manages to alter his settings and services.

The Apple Scruffs (my affectionate name for the wonderful telephone support guys) are happy to support me to recover Dylan’s music as often as he needs, but clearly it would be better if he wasn’t able to lose it in the first place. One of the Scruffs advised that I send some feedback to Apple, suggesting that they put an option for preventing the removal of downloaded music on Parental Controls. I never had a response to that request – presumably it isn’t a priority as Apple want to encourage the use of their subscription streaming service rather than downloaded purchases. So, as things stand, Dylan has hundreds of pounds worth of films and music which he has bought via iTunes, but which he cannot use. These will, of course, remain his personal purchases and at some time in the future, hopefully, he will be re-united with his iPad and able to enjoy these again. At least, that’s what I’m telling myself …

Support and Technology

What the recent problem with the iPad has demonstrated is that, given the built-in obstacles in the technology, Dylan requires support to use it. Dylan generally recognises when he needs support with something language-based and will request this. However, the personal usage data suggests that Dylan had been spending significant amounts of time on his iPad. The reality is that if staff are not available (or able) to support Dylan with the technology, rather than a resource it becomes a source of frustration and anger, leading both the technology and Dylan to breakdown.

What the recent problem with the iPad has demonstrated is that, given the built-in obstacles in the technology, Dylan requires support to use it. Dylan generally recognises when he needs support with something language-based and will request this. However, the personal usage data suggests that Dylan had been spending significant amounts of time on his iPad. The reality is that if staff are not available (or able) to support Dylan with the technology, rather than a resource it becomes a source of frustration and anger, leading both the technology and Dylan to breakdown.

When I confiscated Dylan’s iPad I was aware this would be difficult for him. I told Dylan the iPad was ‘broken’ (which Dylan knew because he had shown me that the music had disappeared). This time, I told him, it had to ‘go to the shop’ to be fixed, but for how long would he accept that story? Confiscating the iPad would also be challenging for support staff. Not only would they have to field Dylan’s questions and manage any incidents arising from my removal of the iPad, they would need to find something else to occupy Dylan’s time. Turkle might approve of what I had done, but I wasn’t sure the care staff would.

I held my breath as I explained to the team leader that I was returning Dylan to the home without his iPad. To my surprise, she reacted positively; she’d had a hunch, she said, that many of the ‘incidents’ involving Dylan were caused by his frustration with his iPad. Perhaps removing it would reduce Dylan’s stress and mean there were fewer incidents of ‘challenging behaviour’?

Dylan and Technology

At the time of writing (11 weeks after I confiscated the iPad) there is some evidence to suggest that the iPad had become a source of distress for Dylan rather than a support; certainly there has been a reduction in the total number of incidents when Dylan has become upset at the care home. I’ve been most struck, however, by the ease with which Dylan has accepted the change. Just as I quickly got used to life without my camera phone, so Dylan has adapted to life without his iPad. He asked about it a few times in the early days but hasn’t mentioned it (at least to me) for weeks.

At the time of writing (11 weeks after I confiscated the iPad) there is some evidence to suggest that the iPad had become a source of distress for Dylan rather than a support; certainly there has been a reduction in the total number of incidents when Dylan has become upset at the care home. I’ve been most struck, however, by the ease with which Dylan has accepted the change. Just as I quickly got used to life without my camera phone, so Dylan has adapted to life without his iPad. He asked about it a few times in the early days but hasn’t mentioned it (at least to me) for weeks.

Going on holiday last week presented me with a dilemma, however. Dylan would need access to his music and films while we were away. Should I produce his iPad (music restored)? If I did, Dylan would expect to keep it on our return from holiday and the cycle would begin again: staff not available to supervise – Dylan spending too much time on his iPad – music lost – Dylan frustrated – challenging behaviour – me back on the phone to the Apple scruffs. Nothing about that felt positive. So instead, I bought a portable DVD/CD player for Dylan to take on holiday with a selection of discs. Old technology it may be, but it worked a treat.

In terms of new technology, the dream for the future is that tech companies give more thought to designing (or adapting) products so that they are accessible to adults who are non-verbal with intellectual disability. Perhaps that’s a pipe dream. In the meantime, it surely isn’t too much to ask that all disabled adults in care receive the support they need to access technology safely and effectively?

Notes:

The photos of Sherry Turkle and the iphone are free stock images. The other photos are of Dylan’s iPad and were taken by me. The final photo is the view from a window of our holiday cottage in Marske-by-the-Sea, taken opportunistically one morning while Dylan was still sleeping.

Johnathan Franzen, ‘Capitalism in Hyperdrive (on Sherry Turkle)’, pp 67-74, in The End of the End of the Earth: Essays (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018)

It didn’t take long, following Dylan’s autism diagnosis, for me to realise that visual images – photographs, symbols, videos – would play a central role in his life. One of my earliest memories of that time is of walking around the village where we lived, photographing places we visited to add to the communication book I was making. It was 1996 and Dylan had just turned two. Digital photography and mobile phones had not yet landed. I shot rolls and rolls of film in those early years and (with an industrial camera which made my shoulder ache) produced numerous home videos – not to record, celebrate or share our lives, as is the case today, but as teaching resources for Dylan’s home education programme and communication aids to support our family life.

It didn’t take long, following Dylan’s autism diagnosis, for me to realise that visual images – photographs, symbols, videos – would play a central role in his life. One of my earliest memories of that time is of walking around the village where we lived, photographing places we visited to add to the communication book I was making. It was 1996 and Dylan had just turned two. Digital photography and mobile phones had not yet landed. I shot rolls and rolls of film in those early years and (with an industrial camera which made my shoulder ache) produced numerous home videos – not to record, celebrate or share our lives, as is the case today, but as teaching resources for Dylan’s home education programme and communication aids to support our family life. Such visual supports are helpful for any child who receives an autism diagnosis but for Dylan, who has remained non-verbal, they are essential. The visual world is Dylan’s language, his ‘mother tongue’. At 28 years old, Dylan has a vast visual vocabulary, supported by thousands of photographs taken over the course of his life. Dylan processes, organises and records visual information at astonishing speed. He can scan an environment and log it visually within minutes. When Dylan is given his visual programme for the day, his eyes flick quickly through the images, absorbing the information. If he encounters an unfamiliar symbol or photograph, he scrutinises it intently, looking for clues, before asking for more information or (sometimes) becoming anxious about what he doesn’t understand.

Such visual supports are helpful for any child who receives an autism diagnosis but for Dylan, who has remained non-verbal, they are essential. The visual world is Dylan’s language, his ‘mother tongue’. At 28 years old, Dylan has a vast visual vocabulary, supported by thousands of photographs taken over the course of his life. Dylan processes, organises and records visual information at astonishing speed. He can scan an environment and log it visually within minutes. When Dylan is given his visual programme for the day, his eyes flick quickly through the images, absorbing the information. If he encounters an unfamiliar symbol or photograph, he scrutinises it intently, looking for clues, before asking for more information or (sometimes) becoming anxious about what he doesn’t understand. The photos developed from hundreds of rolls of analogue film have, of course, been superseded by digital images stored on various devices: computers, lap tops, iPads, iPhone and USB sticks. These technological developments may not have been made with disabled people in mind but they have helped to meet Dylan’s needs as a non-verbal autistic man with an intellectual disability. In particular, phone-based photography has given Dylan access to a portable archive which he uses for a range of purposes. Dylan browses the photos on my phone to communicate, for personal pleasure and for reassurance. Sometimes, multiple functions are served at once; while having a drink in a pub, for example, Dylan will scroll through the images on my phone while I read, the pleasure and reassurance he finds in this activity punctuated by conversations about selected images.

The photos developed from hundreds of rolls of analogue film have, of course, been superseded by digital images stored on various devices: computers, lap tops, iPads, iPhone and USB sticks. These technological developments may not have been made with disabled people in mind but they have helped to meet Dylan’s needs as a non-verbal autistic man with an intellectual disability. In particular, phone-based photography has given Dylan access to a portable archive which he uses for a range of purposes. Dylan browses the photos on my phone to communicate, for personal pleasure and for reassurance. Sometimes, multiple functions are served at once; while having a drink in a pub, for example, Dylan will scroll through the images on my phone while I read, the pleasure and reassurance he finds in this activity punctuated by conversations about selected images. My mobile phone is packed with photos, the vast majority involving Dylan in some way. They are records of places we have visited, mostly landscape but sometimes featuring one or both of us (sometimes ‘selfies’ but more often not) generally taken by me but a few by Dylan, my daughter or friends. The gallery is added to on a weekly basis, when Dylan comes for home visits, and more often during holidays and trips. But here’s a thing. The most recent photo of Dylan on my phone is a selfie of us at Cleethorpes, taken on New Year’s Day. Dylan has made numerous home visits, since then, and we have been on overnight trips and spent a week in Wales. But, except for one landscape shot taken in Wales on 21st April, there is no record on my phone of these visits.

My mobile phone is packed with photos, the vast majority involving Dylan in some way. They are records of places we have visited, mostly landscape but sometimes featuring one or both of us (sometimes ‘selfies’ but more often not) generally taken by me but a few by Dylan, my daughter or friends. The gallery is added to on a weekly basis, when Dylan comes for home visits, and more often during holidays and trips. But here’s a thing. The most recent photo of Dylan on my phone is a selfie of us at Cleethorpes, taken on New Year’s Day. Dylan has made numerous home visits, since then, and we have been on overnight trips and spent a week in Wales. But, except for one landscape shot taken in Wales on 21st April, there is no record on my phone of these visits. The photo in Wales (on the left) was taken to see if Dylan would allow me to use my camera phone after months of him objecting. How many months? At least five, maybe more. I can’t pinpoint exactly when it started. I wish I could because then I might be able to work out why. Looking back at the photos of Dylan on my phone immediately before New Year’s Day, he seems to be smiling and happy. There are fewer than in previous years, perhaps. Now, as I search my online records, I see that on 26th December I reflected to friends that Dylan seemed to ‘have become camera shy’ and reported that I’d shaved him in case he disliked his full beard. So, Dylan was already feeling uncomfortable about phone photographs in December?

The photo in Wales (on the left) was taken to see if Dylan would allow me to use my camera phone after months of him objecting. How many months? At least five, maybe more. I can’t pinpoint exactly when it started. I wish I could because then I might be able to work out why. Looking back at the photos of Dylan on my phone immediately before New Year’s Day, he seems to be smiling and happy. There are fewer than in previous years, perhaps. Now, as I search my online records, I see that on 26th December I reflected to friends that Dylan seemed to ‘have become camera shy’ and reported that I’d shaved him in case he disliked his full beard. So, Dylan was already feeling uncomfortable about phone photographs in December?  And now I think about it, perhaps that could explain the day I had to report an ‘incident’ during a home visit (such a rare occurrence that the care home manager commented to me that she was surprised to see the report). Dylan and I were completing a familiar and much-loved walk when he became distressed and started jumping wildly (one of Dylan’s anxiety behaviours) at the edge of a steep path. It was a difficult situation for me to manage and I was badly shaken, especially as I didn’t know what had triggered it. But now I remember that I had taken my phone out to photograph the valley. According to my diary that was 17th October. Could Dylan really have been anxious about photos as long ago as that? How much discomfort might I have put him through before he managed to communicate this to me?

And now I think about it, perhaps that could explain the day I had to report an ‘incident’ during a home visit (such a rare occurrence that the care home manager commented to me that she was surprised to see the report). Dylan and I were completing a familiar and much-loved walk when he became distressed and started jumping wildly (one of Dylan’s anxiety behaviours) at the edge of a steep path. It was a difficult situation for me to manage and I was badly shaken, especially as I didn’t know what had triggered it. But now I remember that I had taken my phone out to photograph the valley. According to my diary that was 17th October. Could Dylan really have been anxious about photos as long ago as that? How much discomfort might I have put him through before he managed to communicate this to me? Now, because I’m alert to Dylan’s discomfort, he only has to say ‘no, no’ and wave his hand. I thought that I had always asked Dylan for his consent before taking his picture, but I realise now that I probably did this in the same way that I ask my dad or daughter for permission to photograph them. Dylan needs to be given more opportunity to communicate consent or refusal than a neurotypical person because he doesn’t have access to the usual strategies, such as spoken language. Obviously, since Dylan has refused to be photographed I’ve stopped sharing pictures online and I’ve been giving some thought to archival material (such as on this blog) and reflecting on ethical and other implications. However, I’m not convinced that whatever is underlying this is quite as straightforward for Dylan…

Now, because I’m alert to Dylan’s discomfort, he only has to say ‘no, no’ and wave his hand. I thought that I had always asked Dylan for his consent before taking his picture, but I realise now that I probably did this in the same way that I ask my dad or daughter for permission to photograph them. Dylan needs to be given more opportunity to communicate consent or refusal than a neurotypical person because he doesn’t have access to the usual strategies, such as spoken language. Obviously, since Dylan has refused to be photographed I’ve stopped sharing pictures online and I’ve been giving some thought to archival material (such as on this blog) and reflecting on ethical and other implications. However, I’m not convinced that whatever is underlying this is quite as straightforward for Dylan… Dylan’s current objection to photography goes beyond my taking his picture; he objects to my taking any photographs at all. There are only 16 shots In my mobile phone gallery since I photographed the two of us on New Year’s Day. With the exception of the photo in Wales, they were all taken when Dylan wasn’t with me. Even if I reassure Dylan that I am not going to take a picture of him, he still says ‘no, no’ and waves his hands if I get my phone out. Sometimes he tries to grab the phone from me and once or twice he has become distressed enough for this to threaten to lead to the jumping which signals anxiety.

Dylan’s current objection to photography goes beyond my taking his picture; he objects to my taking any photographs at all. There are only 16 shots In my mobile phone gallery since I photographed the two of us on New Year’s Day. With the exception of the photo in Wales, they were all taken when Dylan wasn’t with me. Even if I reassure Dylan that I am not going to take a picture of him, he still says ‘no, no’ and waves his hands if I get my phone out. Sometimes he tries to grab the phone from me and once or twice he has become distressed enough for this to threaten to lead to the jumping which signals anxiety.  Obviously, this is a risk I have not been prepared to take for the sake of a photo of, for example, Devil’s Bridge at Pontarfynach. Our visit there at Easter was the highlight of Dylan’s holiday. Dylan was utterly transfixed by the chaos of water and stone and he lingered at the Punchbowl and viewing platforms on Jacob’s Ladder as long as I would let him. Previously, Dylan would have wanted me to photograph this magical place so that he could return to images of it whenever he wanted. ‘Do you want me to take a photograph of the water for you, Dylan?’ ‘No, no, no’. Of course, I could not risk Dylan jumping into the Mynach Falls. Serendipitously, on this occasion, a print of Devil’s Bridge was hanging in our holiday cottage and every evening Dylan would stand before it, entranced. Since we returned from our holiday I have bought a copy of the print (Clever Girl) and a sister piece (Spring) by the same artist, Chloe Rodenhurst, so that Dylan can continue to enjoy the visual world that speaks so eloquently to him (if no longer via photographs).

Obviously, this is a risk I have not been prepared to take for the sake of a photo of, for example, Devil’s Bridge at Pontarfynach. Our visit there at Easter was the highlight of Dylan’s holiday. Dylan was utterly transfixed by the chaos of water and stone and he lingered at the Punchbowl and viewing platforms on Jacob’s Ladder as long as I would let him. Previously, Dylan would have wanted me to photograph this magical place so that he could return to images of it whenever he wanted. ‘Do you want me to take a photograph of the water for you, Dylan?’ ‘No, no, no’. Of course, I could not risk Dylan jumping into the Mynach Falls. Serendipitously, on this occasion, a print of Devil’s Bridge was hanging in our holiday cottage and every evening Dylan would stand before it, entranced. Since we returned from our holiday I have bought a copy of the print (Clever Girl) and a sister piece (Spring) by the same artist, Chloe Rodenhurst, so that Dylan can continue to enjoy the visual world that speaks so eloquently to him (if no longer via photographs). I might not have risked photographing the Mynach Falls but I did conduct an experiment that week. One of the theories I’ve developed is that Dylan dislikes me using my phone rather than the phone camera. Could he be trying to sabotage my conversations with his sister? Maybe he doesn’t like the effect of speaker phone on language. Or perhaps Dylan resents any time I spend on my phone (checking for news and email) and wants my attention to himself. Quite right too. Or (a wilder hypothesis) could he have developed anxiety about my phone as a result of a specific incident? Dylan may, for example, have made a connection between my mobile phone and a Lateral Flow Test he had to take for Disney on Ice (due to a problem with the notification). That was in December which might fit with the Christmas/New Year dates (but wouldn’t explain the October incident I’ve recalled while writing this blog). To test whether Dylan’s protest is about my phone or my photography, I took my old digital camera on our trip to Wales.

I might not have risked photographing the Mynach Falls but I did conduct an experiment that week. One of the theories I’ve developed is that Dylan dislikes me using my phone rather than the phone camera. Could he be trying to sabotage my conversations with his sister? Maybe he doesn’t like the effect of speaker phone on language. Or perhaps Dylan resents any time I spend on my phone (checking for news and email) and wants my attention to himself. Quite right too. Or (a wilder hypothesis) could he have developed anxiety about my phone as a result of a specific incident? Dylan may, for example, have made a connection between my mobile phone and a Lateral Flow Test he had to take for Disney on Ice (due to a problem with the notification). That was in December which might fit with the Christmas/New Year dates (but wouldn’t explain the October incident I’ve recalled while writing this blog). To test whether Dylan’s protest is about my phone or my photography, I took my old digital camera on our trip to Wales. I was able to take 14 photographs that week, including one of Dylan under the Jubilee Arch at Hafod (which I won’t share). I would say that Dylan wasn’t super relaxed but he gave consent and seemed happy enough. It was for this reason I attempted to take a photo with my mobile phone on 21st April. Having used my Fujifilm all week, how would Dylan react to the iPhone? I took the shot but Dylan wasn’t at all happy about it and, given the terrain, I put my phone away. What do I surmise from this? It may be the phone, rather than the phone camera, which makes Dylan anxious, but I need more evidence. If it is the phone, then I have a not-insignificant problem. I need to be able to use my mobile in emergencies and for navigation. I should be able to take calls from friends and family if they need me. I have to be able to use digital apps (railcards for example) when we are in the community. And, importantly, I need to be able to record medical and other incidents for Dylan’s records.

I was able to take 14 photographs that week, including one of Dylan under the Jubilee Arch at Hafod (which I won’t share). I would say that Dylan wasn’t super relaxed but he gave consent and seemed happy enough. It was for this reason I attempted to take a photo with my mobile phone on 21st April. Having used my Fujifilm all week, how would Dylan react to the iPhone? I took the shot but Dylan wasn’t at all happy about it and, given the terrain, I put my phone away. What do I surmise from this? It may be the phone, rather than the phone camera, which makes Dylan anxious, but I need more evidence. If it is the phone, then I have a not-insignificant problem. I need to be able to use my mobile in emergencies and for navigation. I should be able to take calls from friends and family if they need me. I have to be able to use digital apps (railcards for example) when we are in the community. And, importantly, I need to be able to record medical and other incidents for Dylan’s records.  Recently, for example, Dylan sustained a cut on the head which I asked him if I could photograph with my phone. Dylan refused and the cut had to be photographed without Dylan’s consent by the care home. While not ideal, there will be other incidents and injuries, particularly given Dylan’s epilepsy, which need to be recorded in this way. I’m told that care home staff photograph Dylan using a variety of devices, including iPhones, but I don’t know whether this is with Dylan’s consent or if he has ever protested about it. Is it only my phone that Dylan objects to? I need more information. Meantime, I am trying to stay alert and open enough to hear what it is Dylan is trying to communicate and work out why. I’d be glad to hear from anyone who has experienced anything similar or has new ideas and fresh eyes.

Recently, for example, Dylan sustained a cut on the head which I asked him if I could photograph with my phone. Dylan refused and the cut had to be photographed without Dylan’s consent by the care home. While not ideal, there will be other incidents and injuries, particularly given Dylan’s epilepsy, which need to be recorded in this way. I’m told that care home staff photograph Dylan using a variety of devices, including iPhones, but I don’t know whether this is with Dylan’s consent or if he has ever protested about it. Is it only my phone that Dylan objects to? I need more information. Meantime, I am trying to stay alert and open enough to hear what it is Dylan is trying to communicate and work out why. I’d be glad to hear from anyone who has experienced anything similar or has new ideas and fresh eyes.  I had the idea to take Dylan to the Isle of Man after reading that it was the basis for the Thomas the Tank Engine stories. The Isle of Man forms the Diocese of ‘Sodor and Man’ and the island’s Bishop is known as ‘Bishop of Sodor and Man’. There is, however, no island of Sodor; the name is Old Norse and refers to the Scottish Hebrides which were once part of ‘The Kingdom of Mann and the Isles’ but over which the Bishop no longer has authority. The Reverend W Awdry modelled his fictional Island of Sodor on the Isle of Man, inspired by holidays he spent there as a child.

I had the idea to take Dylan to the Isle of Man after reading that it was the basis for the Thomas the Tank Engine stories. The Isle of Man forms the Diocese of ‘Sodor and Man’ and the island’s Bishop is known as ‘Bishop of Sodor and Man’. There is, however, no island of Sodor; the name is Old Norse and refers to the Scottish Hebrides which were once part of ‘The Kingdom of Mann and the Isles’ but over which the Bishop no longer has authority. The Reverend W Awdry modelled his fictional Island of Sodor on the Isle of Man, inspired by holidays he spent there as a child.

For many academics, now (before the marking comes in) is the ideal time to get away to a conference. As well as providing feedback on work in progress, conferences are a chance to network with colleagues from other institutions.

For many academics, now (before the marking comes in) is the ideal time to get away to a conference. As well as providing feedback on work in progress, conferences are a chance to network with colleagues from other institutions. Developing enough self-awareness to recognise conferences make me uncomfortable was helpful but it took years for me to admit that I didn’t enjoy them, even after I’d stopped going. Then, a couple of years ago, I was asked to give a presentation at a National Autistic Society (NAS) conference. This presented me with a dilemma. I had been asked to contribute a parent’s perspective of supporting a young person with autism and intellectual disability (i.e. Dylan) into adult services. This was a story I felt passionate about sharing; the experiences of ‘non-verbal’ autistic children and adults with a co-morbid diagnosis of intellectual disability are so often overlooked and I was delighted that the conference organisers were making space to represent a narrative from this group.

Developing enough self-awareness to recognise conferences make me uncomfortable was helpful but it took years for me to admit that I didn’t enjoy them, even after I’d stopped going. Then, a couple of years ago, I was asked to give a presentation at a National Autistic Society (NAS) conference. This presented me with a dilemma. I had been asked to contribute a parent’s perspective of supporting a young person with autism and intellectual disability (i.e. Dylan) into adult services. This was a story I felt passionate about sharing; the experiences of ‘non-verbal’ autistic children and adults with a co-morbid diagnosis of intellectual disability are so often overlooked and I was delighted that the conference organisers were making space to represent a narrative from this group. So I went to the conference and, happily, all was well. I think this was because of the company of a couple of people I felt comfortable with and the privileged access I enjoyed, as a speaker, to a sort of ‘green room’. I made heavy use of the room, retreating there with my plate of food at mealtimes and in-between sessions. I was conscious, during the conference, that I would probably not have found the event so comfortable were I attending as a delegate. The NAS had introduced some thoughtful practices (such as the red badges) but these could not counter the usual challenges.

So I went to the conference and, happily, all was well. I think this was because of the company of a couple of people I felt comfortable with and the privileged access I enjoyed, as a speaker, to a sort of ‘green room’. I made heavy use of the room, retreating there with my plate of food at mealtimes and in-between sessions. I was conscious, during the conference, that I would probably not have found the event so comfortable were I attending as a delegate. The NAS had introduced some thoughtful practices (such as the red badges) but these could not counter the usual challenges. Soon after I returned from the conference a friend told me how, meeting a new group of people for the first time, she had taken the hand of a man to shake it in greeting. But, she cringed, it turned out he wasn’t actually offering his hand: “imagine how embarrassed I felt”, she said to me. I could, I reassured her; I had been equally embarrassed not to take a hand that was offered to me at an event at the NAS conference. The hand I failed to shake belonged to someone who identifies as autistic and (I realised later when she confronted me about it) it had mattered to her that I hadn’t returned that handshake. “I hadn’t meant to offend”, I told my friend. “Like you, I just misread the signals.”

Soon after I returned from the conference a friend told me how, meeting a new group of people for the first time, she had taken the hand of a man to shake it in greeting. But, she cringed, it turned out he wasn’t actually offering his hand: “imagine how embarrassed I felt”, she said to me. I could, I reassured her; I had been equally embarrassed not to take a hand that was offered to me at an event at the NAS conference. The hand I failed to shake belonged to someone who identifies as autistic and (I realised later when she confronted me about it) it had mattered to her that I hadn’t returned that handshake. “I hadn’t meant to offend”, I told my friend. “Like you, I just misread the signals.” What I quickly realised at the conference, however, was that autistic delegates were made very uncomfortable (understandably) by presentations which adopted a medical approach to autism and by the use of terminology which is not that preferred by the ‘autistic community’. One presenter came in for a particularly rough ride. He was presenting research from a project which drew on development psychology and which was not framed within the discourse of a social model of disability. A number of articulate autistic delegates challenged the project’s attempt to scientifically classify different ‘autisms’ and the medical language which the presenter used. While I understood the objections of autistic delegates, I didn’t share the view that the presentation should not have been included in the Conference programme; on the contrary, I welcomed the challenge and an opportunity to think differently.

What I quickly realised at the conference, however, was that autistic delegates were made very uncomfortable (understandably) by presentations which adopted a medical approach to autism and by the use of terminology which is not that preferred by the ‘autistic community’. One presenter came in for a particularly rough ride. He was presenting research from a project which drew on development psychology and which was not framed within the discourse of a social model of disability. A number of articulate autistic delegates challenged the project’s attempt to scientifically classify different ‘autisms’ and the medical language which the presenter used. While I understood the objections of autistic delegates, I didn’t share the view that the presentation should not have been included in the Conference programme; on the contrary, I welcomed the challenge and an opportunity to think differently. One of the best sessions I went to focused on language; a panel of ‘experts’ made position statements before a general question and answer session with the audience. The discussion was useful with deep attention paid to choices about person first and identity first language. The knotty issue of whether autism could ever be an ‘identity’ for someone with intellectual disability and who ‘lacks capacity’, however, was not tackled. Nor was there a single mention of the difficulty posed by ‘learning disability’ as opposed to ‘intellectual disability’. As is perhaps clear from my own language choice, I prefer the term ‘intellectual disability’. This is because I find it a more exact way to describe Dylan, who is perfectly capable of learning and who is learning all the time; the fact that Dylan has not learned the same things as other people of his age is because he has a cognitive ‘impairment’ – a disability of the intellect – and not because he is unable to learn.

One of the best sessions I went to focused on language; a panel of ‘experts’ made position statements before a general question and answer session with the audience. The discussion was useful with deep attention paid to choices about person first and identity first language. The knotty issue of whether autism could ever be an ‘identity’ for someone with intellectual disability and who ‘lacks capacity’, however, was not tackled. Nor was there a single mention of the difficulty posed by ‘learning disability’ as opposed to ‘intellectual disability’. As is perhaps clear from my own language choice, I prefer the term ‘intellectual disability’. This is because I find it a more exact way to describe Dylan, who is perfectly capable of learning and who is learning all the time; the fact that Dylan has not learned the same things as other people of his age is because he has a cognitive ‘impairment’ – a disability of the intellect – and not because he is unable to learn. I intended to write this piece immediately after the conference; I have no idea why it has taken me so long to write, except that I find these issues challenging and my position is still evolving. I’ve no doubt that the piece I am finishing today is a very different one to the one I would have written two years ago. What hasn’t changed, however, is the main impression I came away from the conference with: that little attention is paid to those like Dylan who have intellectual disability as well as autism. Great leaps forward have been made for many autistic people in recent years, largely because of their own efforts and the fantastic contribution they have made to campaigning organisations, such as the National Autistic Society, through self-advocacy. Part of me is heartened by this but I am also worried that the different interests of those who can’t self-advocate are lost in this process.

I intended to write this piece immediately after the conference; I have no idea why it has taken me so long to write, except that I find these issues challenging and my position is still evolving. I’ve no doubt that the piece I am finishing today is a very different one to the one I would have written two years ago. What hasn’t changed, however, is the main impression I came away from the conference with: that little attention is paid to those like Dylan who have intellectual disability as well as autism. Great leaps forward have been made for many autistic people in recent years, largely because of their own efforts and the fantastic contribution they have made to campaigning organisations, such as the National Autistic Society, through self-advocacy. Part of me is heartened by this but I am also worried that the different interests of those who can’t self-advocate are lost in this process. Dylan turned 23 this month. To celebrate his birthday I took him to Chester for a short break. A trip to the zoo and an overnight stay in a ‘moon hotel’ was followed by a day walking the city walls and looking at the river, canals and cathedral. These are things which Dylan loves and we had a marvellous time.

Dylan turned 23 this month. To celebrate his birthday I took him to Chester for a short break. A trip to the zoo and an overnight stay in a ‘moon hotel’ was followed by a day walking the city walls and looking at the river, canals and cathedral. These are things which Dylan loves and we had a marvellous time. I didn’t have a particular gift in mind for Dylan this year so I looked around a ‘gifts and novelties’ section of a department store for inspiration. As well as the car, I picked out a ‘Gentleman’s Hardware’ picnic box which Dylan seems to be enjoying. He often takes a packed lunch on his trips out so this is something he’ll get lots of use out of. While I was in the store, my attention was also caught by a box of ‘Emotes’…

I didn’t have a particular gift in mind for Dylan this year so I looked around a ‘gifts and novelties’ section of a department store for inspiration. As well as the car, I picked out a ‘Gentleman’s Hardware’ picnic box which Dylan seems to be enjoying. He often takes a packed lunch on his trips out so this is something he’ll get lots of use out of. While I was in the store, my attention was also caught by a box of ‘Emotes’… Because Dylan uses symbols to communicate I’m always on the look out for visual resources and the Emotes looked interesting. Essentially, the product is an emoticon glossary, presented as a card index: one side of the card has a picture of an emoticon and the reverse side carries a definition and explanation of use. A fun present for a social media junkie. I flicked through the cards in the box, embarrassed (by how much I had misunderstood) and amused (pile of poo? really?).

Because Dylan uses symbols to communicate I’m always on the look out for visual resources and the Emotes looked interesting. Essentially, the product is an emoticon glossary, presented as a card index: one side of the card has a picture of an emoticon and the reverse side carries a definition and explanation of use. A fun present for a social media junkie. I flicked through the cards in the box, embarrassed (by how much I had misunderstood) and amused (pile of poo? really?). I don’t text very much or use social media language. I understand happy and sad faces, and I include them in messages sometimes, but that’s about my limit. I’m too scared of making a faux pas after spending years thinking that ‘lol’ meant ‘lots of love’ and wondering why people I hardly knew kept sending it to me. Now, I try and avoid inserting funny faces into my emails and texts.

I don’t text very much or use social media language. I understand happy and sad faces, and I include them in messages sometimes, but that’s about my limit. I’m too scared of making a faux pas after spending years thinking that ‘lol’ meant ‘lots of love’ and wondering why people I hardly knew kept sending it to me. Now, I try and avoid inserting funny faces into my emails and texts. But while I could clearly learn things from the cards, it wasn’t really myself I was thinking about. Could the emotes help Dylan to understand his emotional life and communicate his feelings, I wondered? Some of the Emotes are the same as makaton signs so would be reassuringly familiar, but there were symbols that might develop nuance and range. Here is worried for example, an emotion which I think Dylan experiences quite frequently:

But while I could clearly learn things from the cards, it wasn’t really myself I was thinking about. Could the emotes help Dylan to understand his emotional life and communicate his feelings, I wondered? Some of the Emotes are the same as makaton signs so would be reassuringly familiar, but there were symbols that might develop nuance and range. Here is worried for example, an emotion which I think Dylan experiences quite frequently:

And there’s even a blank to create your own emote. I like the idea of leaving it empty, actually; having an option for not feeling anything strikes me as pretty useful. While the box includes some inappropriate cards (a gun), others would almost certainly amuse (that pile of poo) or excite Dylan (piece of cake). The set cost £12.00. I decided to buy one – not to gift wrap (Dylan would probably think that a disappointing present) but to introduce as part of the on-going attempt to support Dylan’s communication.

And there’s even a blank to create your own emote. I like the idea of leaving it empty, actually; having an option for not feeling anything strikes me as pretty useful. While the box includes some inappropriate cards (a gun), others would almost certainly amuse (that pile of poo) or excite Dylan (piece of cake). The set cost £12.00. I decided to buy one – not to gift wrap (Dylan would probably think that a disappointing present) but to introduce as part of the on-going attempt to support Dylan’s communication. I don’t think that, so far, they’ve been of much interest to Dylan. When I showed them to him on his birthday he had a giggle at the pile of poo and put the picture of a piece of cake in the plastic stand. Fair enough – this was the bit of his day he was most looking forward to. Dylan also enjoyed the ‘fist bump’ card and quickly grasped this as a greeting or alternative for ‘good job’. Two weeks later, Dylan is still fist-bumping me. The cake is still in the stand, however, and Dylan shows no interest in changing it or in looking at the other symbols. ‘Never say never’, is my mantra, however; Dylan may pick them up one day.

I don’t think that, so far, they’ve been of much interest to Dylan. When I showed them to him on his birthday he had a giggle at the pile of poo and put the picture of a piece of cake in the plastic stand. Fair enough – this was the bit of his day he was most looking forward to. Dylan also enjoyed the ‘fist bump’ card and quickly grasped this as a greeting or alternative for ‘good job’. Two weeks later, Dylan is still fist-bumping me. The cake is still in the stand, however, and Dylan shows no interest in changing it or in looking at the other symbols. ‘Never say never’, is my mantra, however; Dylan may pick them up one day. I do think Emotes are a potentially useful resource for people (children or adults) who struggle to understand socio-emotional communication. And you don’t need to have an autism diagnosis to be in that category lol 🙂

I do think Emotes are a potentially useful resource for people (children or adults) who struggle to understand socio-emotional communication. And you don’t need to have an autism diagnosis to be in that category lol 🙂

So last week Dylan had Facetime scheduled on his programme on Tuesday and Thursday after his evening meal. The icon looked like one of those warning signs for road traffic cameras I thought to myself. I doubted I would be up to speed: I wasn’t even sure I’d created the accounts correctly. If something unexpected happened would I be able to sort it, I wondered? Or would techno-anxiety get the better of me?

So last week Dylan had Facetime scheduled on his programme on Tuesday and Thursday after his evening meal. The icon looked like one of those warning signs for road traffic cameras I thought to myself. I doubted I would be up to speed: I wasn’t even sure I’d created the accounts correctly. If something unexpected happened would I be able to sort it, I wondered? Or would techno-anxiety get the better of me?

As Dylan didn’t understand what the Facetime symbol on his programme meant he didn’t have the fear I had but nor did he know what to expect. For our first session Dylan was in the corridor outside his room as if unsure where to locate this new activity on his mental map. I wasn’t surprised – even with some awareness of what would happen I’d wondered where in the house to sit for our Facetime call.

As Dylan didn’t understand what the Facetime symbol on his programme meant he didn’t have the fear I had but nor did he know what to expect. For our first session Dylan was in the corridor outside his room as if unsure where to locate this new activity on his mental map. I wasn’t surprised – even with some awareness of what would happen I’d wondered where in the house to sit for our Facetime call. Dylan had a second Facetime session scheduled for Thursday. After our first session I had emailed staff to say that I thought it had gone well but I would understand if Dylan didn’t want to do it again. I then tried to be as good as my word by not looking forward to our Thursday evening arrangement too much in case it didn’t happen.

Dylan had a second Facetime session scheduled for Thursday. After our first session I had emailed staff to say that I thought it had gone well but I would understand if Dylan didn’t want to do it again. I then tried to be as good as my word by not looking forward to our Thursday evening arrangement too much in case it didn’t happen.

It’s not Dylan who is kicking and screaming, this time, but me: all the way into the 21st century. As you might have gathered I am not keen on the digital world. While colleagues book out laptops for seminars I am still using the laminator and asking the technician for string and stickle bricks. ‘When you answer the item on your module evaluation questionnaire about my use of technology’, I tell students, ‘please remember that twisting cotton into a ball of twine is technology – it’s just been around a bit longer’.

It’s not Dylan who is kicking and screaming, this time, but me: all the way into the 21st century. As you might have gathered I am not keen on the digital world. While colleagues book out laptops for seminars I am still using the laminator and asking the technician for string and stickle bricks. ‘When you answer the item on your module evaluation questionnaire about my use of technology’, I tell students, ‘please remember that twisting cotton into a ball of twine is technology – it’s just been around a bit longer’. I might have a heart of string and a head that thinks in pen and ink but there’s nothing like parenting to challenge me – and being the peripatetic mother of an autistic adult, I am discovering, can lead to some unexpected places.

I might have a heart of string and a head that thinks in pen and ink but there’s nothing like parenting to challenge me – and being the peripatetic mother of an autistic adult, I am discovering, can lead to some unexpected places. I did buy one, though not for me. The extra capacity and portability would be ideal for Dylan I decided: I could have his old iPad. So yesterday I rigged up a maybe-system for transferring Dylan’s content to the new iPad mini. My main worry was accidentally deleting the copy of Ariel’s Beginnings I had gone to such lengths to

I did buy one, though not for me. The extra capacity and portability would be ideal for Dylan I decided: I could have his old iPad. So yesterday I rigged up a maybe-system for transferring Dylan’s content to the new iPad mini. My main worry was accidentally deleting the copy of Ariel’s Beginnings I had gone to such lengths to

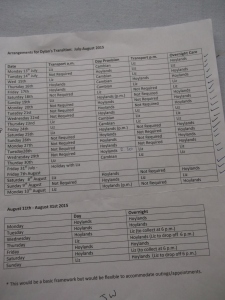

What I am calling phoney time arose through fortune as much as planning. The first stroke of luck was that after Dylan’s residential placement had been approved his day centre requested a month’s notice. Had this not been the case Dylan’s social care-funded day centre placement would have ended one day and his health care-funded residential placement started the next. Clearly this would not have been great from Dylan’s perspective (or from anyone’s except the funders) but this is standard practice and difficult to challenge. The 28 day notice period, however, provided a fortunate opportunity for a programme of interim activities involving home and both providers.

What I am calling phoney time arose through fortune as much as planning. The first stroke of luck was that after Dylan’s residential placement had been approved his day centre requested a month’s notice. Had this not been the case Dylan’s social care-funded day centre placement would have ended one day and his health care-funded residential placement started the next. Clearly this would not have been great from Dylan’s perspective (or from anyone’s except the funders) but this is standard practice and difficult to challenge. The 28 day notice period, however, provided a fortunate opportunity for a programme of interim activities involving home and both providers. Dylan and I had a holiday booked for the fourth week of Dylan’s residential placement. This was not something I had expected earlier in the year; Dylan’s increasingly ‘challenging behaviour’ meant I had resigned myself to not being able to take him away this summer. Dylan loves his holidays so accepting that I could no longer support him by myself had been hard. But isn’t it just the way of things that the minute I made this decision my friend Julie asked whether we would like to rent a holiday cottage with her and daughter Ella 🙂

Dylan and I had a holiday booked for the fourth week of Dylan’s residential placement. This was not something I had expected earlier in the year; Dylan’s increasingly ‘challenging behaviour’ meant I had resigned myself to not being able to take him away this summer. Dylan loves his holidays so accepting that I could no longer support him by myself had been hard. But isn’t it just the way of things that the minute I made this decision my friend Julie asked whether we would like to rent a holiday cottage with her and daughter Ella 🙂 Before we left for our week by the sea it was agreed that when we returned Dylan would be based full time at his new home. Although we were still within the 28 day notice period it was also decided that joint staffing would end and the new setting assume responsibility for Dylan’s care. In this way our holiday would signal the end of the first phase of transition.

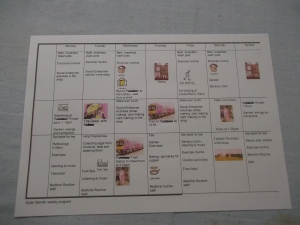

Before we left for our week by the sea it was agreed that when we returned Dylan would be based full time at his new home. Although we were still within the 28 day notice period it was also decided that joint staffing would end and the new setting assume responsibility for Dylan’s care. In this way our holiday would signal the end of the first phase of transition. I’m quite sure this isn’t because Dylan is unhappy in his new home. On the contrary he appears to be having a fine time. Dylan’s programme has been full and varied with the familiar activities he loves as well as new challenges and experiences. He is always happy to return after he has spent time with me and he seems to be settling into his room and to the routines of the home. As well as getting used to new support workers, Dylan is responding well to a communication system which promises to make a positive contribution to his life. Apart from a minor incident on our return from holiday, he has been calm and happy.

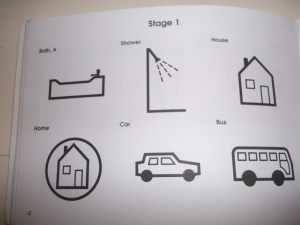

I’m quite sure this isn’t because Dylan is unhappy in his new home. On the contrary he appears to be having a fine time. Dylan’s programme has been full and varied with the familiar activities he loves as well as new challenges and experiences. He is always happy to return after he has spent time with me and he seems to be settling into his room and to the routines of the home. As well as getting used to new support workers, Dylan is responding well to a communication system which promises to make a positive contribution to his life. Apart from a minor incident on our return from holiday, he has been calm and happy. Although a visual timetable helps Dylan make sense of his life in concrete terms (where he will be and what he will be doing) it cannot communicate more abstract concepts. ‘Home’ is a complex idea. It is more than the house where you spend your time; it is the place where you feel safe and loved. The circle around the house in the symbol system which Dylan uses is an attempt to communicate the emotional freight of a building, i.e. that this particular house is the one where you belong. This is not something that can easily be explained however; it is through lived experience that Dylan will come to understand this in his heart.

Although a visual timetable helps Dylan make sense of his life in concrete terms (where he will be and what he will be doing) it cannot communicate more abstract concepts. ‘Home’ is a complex idea. It is more than the house where you spend your time; it is the place where you feel safe and loved. The circle around the house in the symbol system which Dylan uses is an attempt to communicate the emotional freight of a building, i.e. that this particular house is the one where you belong. This is not something that can easily be explained however; it is through lived experience that Dylan will come to understand this in his heart. There is still one more piece I want to write before the end of phoney August. After that I will consider Dylan and I to have crossed the line and I will start a daily diary. Those posts will be different to the ones I have been writing in the last two years and will focus less on Dylan and more on the experience of separation from a parent’s perspective.

There is still one more piece I want to write before the end of phoney August. After that I will consider Dylan and I to have crossed the line and I will start a daily diary. Those posts will be different to the ones I have been writing in the last two years and will focus less on Dylan and more on the experience of separation from a parent’s perspective.