I’ve only very recently started referring to Dylan as my son. For the first 18 years or so of his life I called him ‘my boy’; until the age of around 11 he was ‘my little boy’ and more recently he’s been ‘my big boy’. Of course I understood that for some purposes I needed to use the category ‘son’ – in official documents which asked me to identify our relationship to each other for example – but I preferred not to use the s word if possible.

I’ve only very recently started referring to Dylan as my son. For the first 18 years or so of his life I called him ‘my boy’; until the age of around 11 he was ‘my little boy’ and more recently he’s been ‘my big boy’. Of course I understood that for some purposes I needed to use the category ‘son’ – in official documents which asked me to identify our relationship to each other for example – but I preferred not to use the s word if possible.

The word ‘son’ describes a socially constructed role. The meaning of the role may vary over time and across cultural groups but in each society there is agreement about what the role involves. Our understanding of ‘son’ (and other social roles) is reinforced through powerful socialisation agents such as the family, school, religion and the media. So while nobody has ever explained the role of ‘daughter’ to me, I have developed a pretty clear idea of what this entails in the society and community in which I live.

I’m frequently struck by the use of the words son and daughter by families and midwives at the moment of delivery: ‘Congratulations you have a son’ or ‘We’ve got a daughter’. There’s a voice in my head which counters: ‘No you have a baby boy or girl who may, in time, take on the social role of son or daughter’.

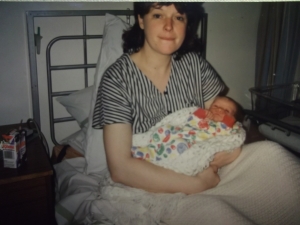

I may argue that a newborn baby isn’t yet a son or daughter, but would I describe the woman who has just given birth as the child’s mother? Mothering is also, after all, a socially constructed role; there is agreement within society about what it involves (that it is a nurturing and educative role) and about perceived transgressions of the role (such as the abandonment of a child). As girls are socialised to the role of ‘mother’ long before they have children of their own, there is a sense in which they are prepared for motherhood before the delivery of their children, unlike the newborn baby who has no awareness of the social roles within the society it has been born into.

I may argue that a newborn baby isn’t yet a son or daughter, but would I describe the woman who has just given birth as the child’s mother? Mothering is also, after all, a socially constructed role; there is agreement within society about what it involves (that it is a nurturing and educative role) and about perceived transgressions of the role (such as the abandonment of a child). As girls are socialised to the role of ‘mother’ long before they have children of their own, there is a sense in which they are prepared for motherhood before the delivery of their children, unlike the newborn baby who has no awareness of the social roles within the society it has been born into.

So what are the implications of this for autism? I would suggest that for someone who is not only autistic but who has a communication and learning disability (‘intellectual disability’ in the US), social roles may not necessarily be clear at all.

Autism and Gender

Sociologists have suggested that the socialisation of children to gender roles begins soon after birth. When my children were born I was determined that I would intervene in some aspects of this process. While I didn’t want to isolate my children from their peer group or from some established norms, I did aim to challenge gendered responses to childhood and education. Both my children were given gender-neutral toys when they were young, were spoken to in gender-free language, and were encouraged to make choices on the basis of their interests rather than according to beliefs about what was ‘gender-appropriate’.

Challenging established practices around gender isn’t easy as I quickly discovered. When my daughter was born she was instantly wrapped in a pink blanket by the nurses. I asked whether it would be possible to find an alternative colour, thinking I may as well start as I meant to go on. The nurses reacted with astonishment but, after attempts to distract me from the request failed, produced a green blanket. They were clearly, however, not comfortable with this; all the other babies in the ward were wrapped in either pink or blue waffle blankets. By the time someone took this early photograph of my daughter, a nurse had tried to re-establish the pink.

Challenging established practices around gender isn’t easy as I quickly discovered. When my daughter was born she was instantly wrapped in a pink blanket by the nurses. I asked whether it would be possible to find an alternative colour, thinking I may as well start as I meant to go on. The nurses reacted with astonishment but, after attempts to distract me from the request failed, produced a green blanket. They were clearly, however, not comfortable with this; all the other babies in the ward were wrapped in either pink or blue waffle blankets. By the time someone took this early photograph of my daughter, a nurse had tried to re-establish the pink.

This was the first of many incidents I encountered while bringing my daughter up to be free of what I considered stereotypes for girls. My ‘little boy’, meanwhile, was growing up marvellously free of any conception of gender whatsoever, quite effortlessly and with absolutely no input from me. Dylan is now aware of biological sex difference – an awareness which I think developed around the time he started needing to shave – but for many years I don’t think he thought of himself as ‘a boy’ particularly. Dylan certainly wasn’t aware of the roles which society thinks of as ‘appropriate’ for boys and girls; he would dress in, behave and interact with whatever interested him, regardless of social conventions around gender. For many years, therefore, I thought of Dylan as ‘gender free’; for me this freedom has been one of the celebratory aspects of living with autism.

I remember an incident when Dylan was young, perhaps nine years old. My mum and I had taken the children to York for the day, an ambitious outing by train which had left us all tired and Dylan a little fretful at the end. Visiting York Minster in the late afternoon there were signs that it was becoming too much for Dylan and we decided to go to a tearoom hoping this would re-orientate him. As sometimes happens, we made the decision five minutes too late; Dylan was already moving into meltdown as we entered the cafe. We happened, that day, to be assigned a magical waitress; a young woman who may or may not have had personal experience of children and/or children with autism. What she had in abundance, though, was an ability to understand and to communicate without language; she noticed Dylan looking at her beads so took these off and gave them to him. The beads were wooden and rough-hewn, threaded on elastic and looped around her wrist. They seemed to calm Dylan like juju beads.

That afternoon tea and cake turned from a potential meltdown into one of the high spots of the day in terms of our sense of well-being. As we left the cafe, heading for the train home, I tipped the waitress and returned her beads. ‘No’ she said: ‘I would like the little man to have these.’ And so she wrapped her beads around Dylan’s wrist and for months afterwards he wore them, and sometimes I did, and we talked about the York waitress until the elastic snapped and we lost them.

Disney Princesses

As well as letting Dylan wear beads I have, over the years, bought toys and resources for him which were clearly aimed at girls rather than boys. I have previously written about Dylan’s love of Disney, a passion which for a long time has been his main interest. At birthdays and Christmas, wanting to give Dylan something that would capture his attention, I have been driven by whichever Disney movie is his current favourite. This has often meant searches for items based on films which are gender-marked female and which feature a princess narrative.

As well as letting Dylan wear beads I have, over the years, bought toys and resources for him which were clearly aimed at girls rather than boys. I have previously written about Dylan’s love of Disney, a passion which for a long time has been his main interest. At birthdays and Christmas, wanting to give Dylan something that would capture his attention, I have been driven by whichever Disney movie is his current favourite. This has often meant searches for items based on films which are gender-marked female and which feature a princess narrative.

One of Dylan’s enduring interests has been Sleeping Beauty. He seems to be attracted by a number of ingredients in this film including the presence of fairies (flying people have long been exciting and seem to underlie his current love of Peter Pan). One scene in particular makes Dylan squeal with pleasure; there is a fight between the fairies as to whether to decorate Aurora’s dress, and later her cake, pink or blue; using their magic wands to alternate the colour, the fairies squabble: ‘make it pink!’ ‘make it blue!’ ‘make it pink!’ ‘make it blue!’ These scenes seem to me to symbolise the gender issue brilliantly- though Dylan probably likes them because of the colours and the cake.

How much influence might these Disney princesses have on children in general and on autistic children in particular? A recent review of the Disney film Frozen in The Guardian Film Blog notes that Disney’s writers are producing increasingly independent and ‘less compliant’ lead female characters. However Anna Smith, the reviewer, bemoans the animators’ continuing use of ‘tiny nipped-in waists, no hips, long legs, skinny arms, pert breasts, small feet and eyes three times the size of the male characters’. While congratulating Disney on the strong female characters at the centre of Frozen (an adaptation of The Snow Queen), and recent female heroes such as Merida in Brave, Smith argues: ‘when so many girls look up to Disney’s princesses as role models, surely it’s time for a rethink of the animation formula.’

How much influence might these Disney princesses have on children in general and on autistic children in particular? A recent review of the Disney film Frozen in The Guardian Film Blog notes that Disney’s writers are producing increasingly independent and ‘less compliant’ lead female characters. However Anna Smith, the reviewer, bemoans the animators’ continuing use of ‘tiny nipped-in waists, no hips, long legs, skinny arms, pert breasts, small feet and eyes three times the size of the male characters’. While congratulating Disney on the strong female characters at the centre of Frozen (an adaptation of The Snow Queen), and recent female heroes such as Merida in Brave, Smith argues: ‘when so many girls look up to Disney’s princesses as role models, surely it’s time for a rethink of the animation formula.’

If girls look up to Disney princesses as role models, what can autistic boys (and girls) possibly make of them? In my earlier post I suggested that Dylan had engaged in social and emotional learning through his interest in Disney. His favourite films, I argued, had helped him to understand social relationships within a family and to recognise different emotions. Does the learning which I described Dylan as engaging in through Disney films extend to learning these stereotypical gender roles? Or even, given Dylan’s love of films with princesses, to him identifying with non-traditional gender roles?

If girls look up to Disney princesses as role models, what can autistic boys (and girls) possibly make of them? In my earlier post I suggested that Dylan had engaged in social and emotional learning through his interest in Disney. His favourite films, I argued, had helped him to understand social relationships within a family and to recognise different emotions. Does the learning which I described Dylan as engaging in through Disney films extend to learning these stereotypical gender roles? Or even, given Dylan’s love of films with princesses, to him identifying with non-traditional gender roles?

During Dylan’s Sleeping Beauty passion I bought him a Princess Palace for Christmas. I thought it would be his heart’s delight but I have to confess that he showed little interest in it and I later donated it to a school fair, virtually unused. Also of only limited interest (though I can’t bring myself to throw it away) is the Snow White musical globe I bought for Dylan at age 13. As I make these reflections I realise that Dylan’s love of Disney films has not particularly translated to an interest in linked resources or toys. Whatever Dylan has learned from Disney, I don’t think it is about gender. Or is it?

During Dylan’s Sleeping Beauty passion I bought him a Princess Palace for Christmas. I thought it would be his heart’s delight but I have to confess that he showed little interest in it and I later donated it to a school fair, virtually unused. Also of only limited interest (though I can’t bring myself to throw it away) is the Snow White musical globe I bought for Dylan at age 13. As I make these reflections I realise that Dylan’s love of Disney films has not particularly translated to an interest in linked resources or toys. Whatever Dylan has learned from Disney, I don’t think it is about gender. Or is it?

Mannequins and Mothers

My sense is that ‘my big boy’ is starting to develop some recognition of social roles; Dylan has recently named a character (Geppetto in Pinocchio) as a ‘daddy’ and he sometimes recognises representations of mothers in storybooks. Dylan has been naming me by my social role (‘moo-ey’) for some time now and perhaps has some idea of the meaning of this label (i.e. that other people also have a mummy). In the first couple of years of Dylan’s life, though, he wasn’t exposed to this role-naming at all.

My sense is that ‘my big boy’ is starting to develop some recognition of social roles; Dylan has recently named a character (Geppetto in Pinocchio) as a ‘daddy’ and he sometimes recognises representations of mothers in storybooks. Dylan has been naming me by my social role (‘moo-ey’) for some time now and perhaps has some idea of the meaning of this label (i.e. that other people also have a mummy). In the first couple of years of Dylan’s life, though, he wasn’t exposed to this role-naming at all.

I was one of those parents who wanted my children to call me by my name rather than by my role. Sure I was the mother of my children, but I wasn’t only that; my identity as a person went beyond my mothering and, knowing how powerful language is, I wanted that to be acknowledged in what my children called me. My children would, of course, know that I was their mother – but they didn’t have to call me mother. So when Dylan was born I called myself Lizzie. Dylan’s autism diagnosis at 23 months changed all that. I decided that I needed to simplify language and concepts and so I started to call myself ‘mummy’ instead. This matched the language Dylan was encountering in his picture books, the media and in society in general. My daughter, just five months old at the time of Dylan’s diagnosis, inevitably shared in this re-naming.

Because of the severity of Dylan’s autism and communication ‘impairment’ it would be many years before Dylan spoke my new name. When he did he was around nine years old; an entry in Dylan’s home-school liaison book reported that he had hugged and said ‘mummy’ to a dressmaker’s mannequin that someone had positioned in the school foyer. ‘That’s a compliment for you’ Dylan’s class teacher had written in the book: ‘she’s very petite and no more than a size 6’ .

Because of the severity of Dylan’s autism and communication ‘impairment’ it would be many years before Dylan spoke my new name. When he did he was around nine years old; an entry in Dylan’s home-school liaison book reported that he had hugged and said ‘mummy’ to a dressmaker’s mannequin that someone had positioned in the school foyer. ‘That’s a compliment for you’ Dylan’s class teacher had written in the book: ‘she’s very petite and no more than a size 6’ .

I am, I hasten to add, not a size 6. If Dylan intended to compare the mannequin to me that day it was not because it reminded him of me specifically, but because of the social role he perceived the mannequin to represent. Given the resemblance between the dimensions of mannequins and Disney princesses, I have to concede the possibility that Dylan may have learned more from Disney about gender and social role than he has from me 😉

Images:

The film images are via Disney and the photographs of Dylan and me were taken by my mother; the other photos are mine.