Dylan in Durham earlier this month…

The trip to Durham might have been successful in all sorts of ways but it didn’t satiate Dylan’s desire for a holiday. We had only been back 24 hours when the questions about ‘cottage’, ‘ sea’ and ‘boat’ started up again. Dylan enjoyed our city break but it wasn’t the holiday he knows, in his sinew and bone, he has not yet had this year and which he is not going to let me forget.

Are you sure we can’t make him a countdown chart to our Summer holiday? I asked the staff at his care home. I have booked a holiday on the Isle of Man, which I have an idea might be Dylan heaven: an overnight hotel en route, a ferry boat crossing, holiday cottage, sea all around us and trains, trams and funiculars. But that isn’t until the end of July. I don’t think we can give him a three month countdown chart, the team leader reflected. Having a picture of the holiday such a long way off could be difficult for Dylan.

So Dylan has continued with just his weekly programme. When he’s asked ‘cottage’ or ‘sea’ or ‘boat’ we’ve said: not this week, Dylan, or later, or sometimes (in desperation) soon Dylan. Of course, none of these are easy, or I suspect meaningful, for Dylan. Time, as I have frequently noted, is one of the most difficult concepts for Dylan to grasp. If you add to this our inability to explain to Dylan the practicalities of work and money, and that we cannot take holidays whenever we want to, then we have a potentially frustrating situation. Dylan is communicating beautifully with us and waiting patiently for a response, but it must feel as if all he is hearing is ‘No’.

The future is a cork board

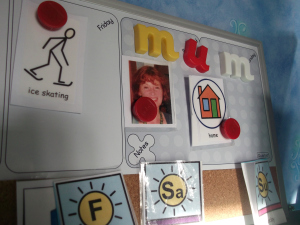

Cork board with countdown chart added

One of our routines, when I return Dylan to his residential setting after his weekend at home, is to go through his weekly programme. Dylan’s programme is fastened to his whiteboard and we talk about everything he will do in the week, ending with my arriving to collect him the following weekend. Dylan points to the pictures and I name them, sometimes signing and sometimes pausing to see whether Dylan is able to name them himself.

When I was talking Dylan through his week a couple of weekends ago, however, his finger didn’t stop pointing when we got to my arrival the following Saturday – instead, he gestured at the cork board to the right of his whiteboard. He walked over to it, stabbing at it with his finger and looking at me quizzically. I’m not sure what you want, Dylan. I said. The member of staff who was with us pointed out that the cork board is where Dylan pins his countdown charts when he has them. He was asking what would happen after next week. So Dylan does have a sense of future time, albeit in a representational way: the future is a cork board.

The shop that sells the sea

So I drove away thinking about our summer holiday and how best to support Dylan with this. I calculated that if I speeded up a bit with my marking I could take a couple of days off work later in the month. Added to a weekend, this would give Dylan four or five days at the coast. That would do it, surely? So later that week I booked a few days on the Yorkshire coast; while we won’t need a boat to get there, it is by the sea and we will be staying in a cottage.

So I drove away thinking about our summer holiday and how best to support Dylan with this. I calculated that if I speeded up a bit with my marking I could take a couple of days off work later in the month. Added to a weekend, this would give Dylan four or five days at the coast. That would do it, surely? So later that week I booked a few days on the Yorkshire coast; while we won’t need a boat to get there, it is by the sea and we will be staying in a cottage.

That afternoon I received Dylan’s weekly update; this is a summary of Dylan’s week with a particular focus on any ‘incidents’. The email opened : Hi Liz, He’s had a really good week this week no incidents so far he has been trying to get into travel agents while in [nearby town] but he was directed away. Trying to get into travel agents! How I laughed. I have never taken Dylan into a travel agents and to my knowledge he has never been in one. And yet he had figured out – presumably from the visual clues in the window – that this is a shop that sells the sea. How clever! Visual intelligence. Initiative. Creativity. Communication. And Dylan’s steel will and determination…

Managing time

I replied to the email to say I’d fixed something up for later this month. The staff were also thinking of ways to respond to Dylan’s requests; his key worker had volunteered to investigate the possibility of taking Dylan on an overnight trip to the coast in June. With countdown charts to the breaks in May and June, Dylan should hopefully find it easier to manage time.

When I saw Dylan last weekend he had the chart with him and seemed to be enjoying crossing off the days. Back at his care home he requested tape to fasten the chart to his cork board, next to his weekly programme (as in the photo above). Dylan didn’t seem as anxious about his schedule when I left and needed less reassurance than the previous week about the ‘sea’ and ‘cottage’ (I am trying to play down the issue of a ‘boat’). When I telephoned for an update last night I was told Dylan has been calm and happy all week and that the chart seems to have helped.

The red book

Perhaps, as Dylan’s understanding of time develops, he will need new strategies for managing it? Something which seemed to help Dylan in the past was his filofax. Although this didn’t have countdown charts and schedules in it, Dylan used it as an ‘object of reference’ for the management of time. He was aware, for example, that it contained the key information and cards he needs to access the activities he enjoys. He carried his filofax everywhere and would bring it to us if he wanted to request an activity. The filofax seemed to be such an important part of Dylan’s life, and so precious to him, that I was horrified when he destroyed it one night when he was anxious and upset about something which the support staff, on that occasion, were unable to fathom.

Perhaps, as Dylan’s understanding of time develops, he will need new strategies for managing it? Something which seemed to help Dylan in the past was his filofax. Although this didn’t have countdown charts and schedules in it, Dylan used it as an ‘object of reference’ for the management of time. He was aware, for example, that it contained the key information and cards he needs to access the activities he enjoys. He carried his filofax everywhere and would bring it to us if he wanted to request an activity. The filofax seemed to be such an important part of Dylan’s life, and so precious to him, that I was horrified when he destroyed it one night when he was anxious and upset about something which the support staff, on that occasion, were unable to fathom.

Since then, we have used a notebook to keep records and pass messages between home and care home. Dylan knows these notebooks have replaced his filofax and he keeps them in the same place, but he has never had quite the same attachment to them. Last weekend I noticed we had filled the last page of his current book so I suggested to Dylan that we go to the store to get a new one. We went to a large Office Supplies shop where Dylan bought his filofax three years ago. As I picked up various notebooks Dylan pushed my hand back towards the shelf in his ‘put it back, I’m not interested’ gesture. This continued all the way up the aisle. Then Dylan escorted me to the filofax section where, after consideration, he picked one out. I suggested some alternatives but he wasn’t having it; Dylan hugged the red book to his chest as if to stop me from taking it from him.

Anxious Times

Dylan stood the empty frame in its usual place when he came home…

I hesitated about buying the filofax for Dylan because it was upsetting when he destroyed the other one – not just for those who care for Dylan, but for Dylan himself. Dylan only ever destroys things which matter to him; he seems to self-regulate, at times of high anxiety, by channelling his emotion through meaningful objects. So although we have made various ‘ripping’ resources available to Dylan, it is his favourite books and DVDs he tears when he is anxious. This means the aftermath of these events is upsetting for Dylan as he realises the loss of things which were important to him.

Dylan tearing possessions to self-regulate could be seen as a positive development in that he used to tear people’s ears when he was anxious, something which he now does only rarely. As the cycle of destroy-replace became increasingly entrenched, however, it no longer felt like a practical strategy. Recently, I’ve been experimenting with not replacing the things which Dylan rips. This has been partly effective in that Dylan hasn’t been tearing books and DVDs as he used to. What it has meant, however, is that his focus sometimes switches to other things.

I was devastated, a few weeks ago, to hear that Dylan had torn the photo of his Gran during an incident. Like filofaxgate, it was the sort of event that was difficult to fathom. Why? Dylan loved that photograph. He kept it by his bed, took it on overnight trips and carried it with him at times of emotional need (or at least that’s how I perceived it). It was, as far as I was concerned, the most precious of his possessions (greater than even his filofax had been) and therefore immune from danger at times of distress. Well, I turned out to be wrong about that. When I told my daughter she was upset (for Dylan) and cross (with me). She reminded me that the photograph had belonged to her, originally. Don’t give Dylan photos of my Gran if you don’t have copies of them, she said.

Changing Times

The ‘duplicate’ of the one Dylan chose…

So the following weekend, when I found Dylan with a photograph of mum he had snaffled from my room, I took it from him: That picture of your Gran belongs to mummy, I said. The next day I went through old albums. I didn’t have the time or energy to make copies right now (a project for retirement maybe) but I found some ‘duplicates’ – photos where another was taken soon after, so there is hardly a difference between the shots. I made an album of these, and some other photos, and showed them to Dylan. Would he like to choose one to keep, I asked?

I was surprised by Dylan’s choice. It is an aerial shot of me and Dylan on a beach in Dorset, taken in 2007. We are absorbed in the pebbles and too far away for Dylan and I to be ‘subjects’ in the photo (unlike the photo of his Gran, which was a portrait shot). Presumably he chose this picture because it reminds him of a happy time? I liked the fact that Dylan replaced the photo of his Gran with something quite different. There is a sense in which it represents him moving on, perhaps; finding new ways of using the past to help manage the present.

About Time

When I collected Dylan last weekend he wasn’t wearing his trademark Breton hat. I was shocked. Dylan is never without that hat; it stays fixed to his head when he is out of the house and he is very good at looking after it. Where is your hat, Dylan? I asked. He hasn’t ripped it, has he? I asked the member of staff who was with him. She didn’t know. In fact she hadn’t noticed that Dylan didn’t have it. But now I had mentioned it, Dylan was on it: lost it, he said, lost it. Then: find it, find it.

When I collected Dylan last weekend he wasn’t wearing his trademark Breton hat. I was shocked. Dylan is never without that hat; it stays fixed to his head when he is out of the house and he is very good at looking after it. Where is your hat, Dylan? I asked. He hasn’t ripped it, has he? I asked the member of staff who was with him. She didn’t know. In fact she hadn’t noticed that Dylan didn’t have it. But now I had mentioned it, Dylan was on it: lost it, he said, lost it. Then: find it, find it.

We checked Dylan’s drawers and cupboards and the cars and rooms of other residents. I drove to the pub where Dylan had been for lunch the previous day. The hat could not be found. Why don’t you wear a different hat for now, I said to Dylan, giving him a choice of three caps from his cupboard. He chose a green one. I’ll sort it out for you I promise, I said to Dylan. I was telling the support worker that I had brought the lost hat back from Brittany and that Dylan had bought his first Breton cap in St Malo when we were on holiday in 2013, when I noticed Dylan looking at me as if he was listening to the conversation (as I think he quite often does). Hey Dylan, I said, perhaps we should go to Brittany next year and get you another hat? Boat, Sea, Cottage I thought to myself as I said this. Dylan rolled his eyes as if to say About time.

It’s a while since I posted an update on Dylan’s progress. Reflecting today I am mostly struck by how well things are going. Christmas isn’t an easy time if you are autistic but Dylan seems to have taken it in his stride this year and coped with the changes in routine which a holiday brings. I suspect that is testament to Dylan’s increasing maturity as well as to our growing understanding of what helps Dylan to manage times of challenge and stress.

It’s a while since I posted an update on Dylan’s progress. Reflecting today I am mostly struck by how well things are going. Christmas isn’t an easy time if you are autistic but Dylan seems to have taken it in his stride this year and coped with the changes in routine which a holiday brings. I suspect that is testament to Dylan’s increasing maturity as well as to our growing understanding of what helps Dylan to manage times of challenge and stress. Dylan seems to have coped with the loss of E, the key worker who settled him into his residential setting and who he had come to love. There were a few incidents in the immediate aftermath of E leaving (to take up a new post) and I was a bit concerned about Dylan. Dylan has experienced the loss of a number of key people from his life over the years, something which has caused him huge sadness and grief. “Mummy will always be here for you”. I sometimes tell Dylan when I think he is grieving. It can’t always be true, I know, but it seems to help.

Dylan seems to have coped with the loss of E, the key worker who settled him into his residential setting and who he had come to love. There were a few incidents in the immediate aftermath of E leaving (to take up a new post) and I was a bit concerned about Dylan. Dylan has experienced the loss of a number of key people from his life over the years, something which has caused him huge sadness and grief. “Mummy will always be here for you”. I sometimes tell Dylan when I think he is grieving. It can’t always be true, I know, but it seems to help. As well as using methods for coping with anxiety that have been suggested to him, Dylan seems to be adopting strategies of his own. He has always been very attached to a photograph of my mum which he keeps by his bed at his residential setting and brings home at weekends. Recently, Dylan has been carrying the photograph with him on day trips as well.

As well as using methods for coping with anxiety that have been suggested to him, Dylan seems to be adopting strategies of his own. He has always been very attached to a photograph of my mum which he keeps by his bed at his residential setting and brings home at weekends. Recently, Dylan has been carrying the photograph with him on day trips as well. I miss my mum as well, of course. Supporting Dylan with his grief helps me to manage my own, especially at times when we are vulnerable, such as Christmas. Dylan carrying the photograph of his Gran around with him enables me to talk about her in a way I might not without such an object of reference for grief. “Your Gran used to like to come here for Christmas Eve, didn’t she?” I said to Dylan as we walked around Castleton village, as we do every year, on the night before Christmas. It’s one of her traditions which I’ve kept going in the belief that continuity helps Dylan to develop a sense of his own life history and place in the world.

I miss my mum as well, of course. Supporting Dylan with his grief helps me to manage my own, especially at times when we are vulnerable, such as Christmas. Dylan carrying the photograph of his Gran around with him enables me to talk about her in a way I might not without such an object of reference for grief. “Your Gran used to like to come here for Christmas Eve, didn’t she?” I said to Dylan as we walked around Castleton village, as we do every year, on the night before Christmas. It’s one of her traditions which I’ve kept going in the belief that continuity helps Dylan to develop a sense of his own life history and place in the world. The concert takes place in the early evening so when we arrive at the cave in the late afternoon the gate is barred and I manage to explain to Dylan that we can’t go in as it is closed for Christmas. When we arrived this year, however, it was to the hum and bustle of an earlier-than-usual concert about to start. The cave was lit like a ship and inside people were seated as the band tuned up. Curious, Dylan pulled on my arm. “You won’t like it Dylan”, I said. “There will be music. And babies.” Dylan continued to pull me over to the gate. The doorman explained there were no tickets anyway: it had sold out in November and two tickets that had been returned that day had been reallocated within five minutes. Dylan, of course, didn’t understand this. He pulled on my arm. “Let’s go, Dylan”, I said. But we were going nowhere – Dylan wanted to go in. I would just have to let things unfold, I decided, and deal with whatever happened.

The concert takes place in the early evening so when we arrive at the cave in the late afternoon the gate is barred and I manage to explain to Dylan that we can’t go in as it is closed for Christmas. When we arrived this year, however, it was to the hum and bustle of an earlier-than-usual concert about to start. The cave was lit like a ship and inside people were seated as the band tuned up. Curious, Dylan pulled on my arm. “You won’t like it Dylan”, I said. “There will be music. And babies.” Dylan continued to pull me over to the gate. The doorman explained there were no tickets anyway: it had sold out in November and two tickets that had been returned that day had been reallocated within five minutes. Dylan, of course, didn’t understand this. He pulled on my arm. “Let’s go, Dylan”, I said. But we were going nowhere – Dylan wanted to go in. I would just have to let things unfold, I decided, and deal with whatever happened. We were given the nod just as the concert was about to begin. This was probably helpful in that we were able to find seats in the far reaches of the cave, beyond the last row of seats. Dylan doesn’t like mince pies but he’d taken the one he was offered and now proceeded (to my amazement) to eat it. The next surprise was that Dylan didn’t cover his ears when the band started up. Another surprise when he started clapping, spontaneously, at the end of the first carol. And then, glory be if he isn’t swaying to the music, stamping his feet and flashing his best grin at me. And so we spent Christmas Eve in a cave – or at least an astonishing 50 minutes of it, leaving only just before the end, when Dylan decided he had heard enough. I was thrilled by the experience, not just for Dylan, but myself: I got to go to a carol concert this year 🙂

We were given the nod just as the concert was about to begin. This was probably helpful in that we were able to find seats in the far reaches of the cave, beyond the last row of seats. Dylan doesn’t like mince pies but he’d taken the one he was offered and now proceeded (to my amazement) to eat it. The next surprise was that Dylan didn’t cover his ears when the band started up. Another surprise when he started clapping, spontaneously, at the end of the first carol. And then, glory be if he isn’t swaying to the music, stamping his feet and flashing his best grin at me. And so we spent Christmas Eve in a cave – or at least an astonishing 50 minutes of it, leaving only just before the end, when Dylan decided he had heard enough. I was thrilled by the experience, not just for Dylan, but myself: I got to go to a carol concert this year 🙂 This was the highlight of my Christmas but there have been other things to enjoy too. Dylan and I spent Christmas Day, as ever, out in the Peak District with a picnic. This year I had chosen Stanage Edge, hankering after a high place. As Dylan’s visual programmes are produced in advance, I have to make decisions about how Dylan and I will spend our time a week before the activity. When I opted for Christmas Day on Stanage Edge, what I didn’t know was that Storm Barbara was due to make landfall and would be passing through the Peak District.

This was the highlight of my Christmas but there have been other things to enjoy too. Dylan and I spent Christmas Day, as ever, out in the Peak District with a picnic. This year I had chosen Stanage Edge, hankering after a high place. As Dylan’s visual programmes are produced in advance, I have to make decisions about how Dylan and I will spend our time a week before the activity. When I opted for Christmas Day on Stanage Edge, what I didn’t know was that Storm Barbara was due to make landfall and would be passing through the Peak District. Our walk that morning would best be described as ‘challenging’; we inched our way along the edge, battered by high winds. At some point I became anxious that we could be blown over the top so spent most of my energy trying to draw Dylan inland through the marsh and bog I would normally steer him round. “Picnic”, Dylan asked hopefully. If it’s on the schedule, not even a storm can blow Dylan off course…

Our walk that morning would best be described as ‘challenging’; we inched our way along the edge, battered by high winds. At some point I became anxious that we could be blown over the top so spent most of my energy trying to draw Dylan inland through the marsh and bog I would normally steer him round. “Picnic”, Dylan asked hopefully. If it’s on the schedule, not even a storm can blow Dylan off course… It’s not Dylan who is kicking and screaming, this time, but me: all the way into the 21st century. As you might have gathered I am not keen on the digital world. While colleagues book out laptops for seminars I am still using the laminator and asking the technician for string and stickle bricks. ‘When you answer the item on your module evaluation questionnaire about my use of technology’, I tell students, ‘please remember that twisting cotton into a ball of twine is technology – it’s just been around a bit longer’.

It’s not Dylan who is kicking and screaming, this time, but me: all the way into the 21st century. As you might have gathered I am not keen on the digital world. While colleagues book out laptops for seminars I am still using the laminator and asking the technician for string and stickle bricks. ‘When you answer the item on your module evaluation questionnaire about my use of technology’, I tell students, ‘please remember that twisting cotton into a ball of twine is technology – it’s just been around a bit longer’. I might have a heart of string and a head that thinks in pen and ink but there’s nothing like parenting to challenge me – and being the peripatetic mother of an autistic adult, I am discovering, can lead to some unexpected places.

I might have a heart of string and a head that thinks in pen and ink but there’s nothing like parenting to challenge me – and being the peripatetic mother of an autistic adult, I am discovering, can lead to some unexpected places. I did buy one, though not for me. The extra capacity and portability would be ideal for Dylan I decided: I could have his old iPad. So yesterday I rigged up a maybe-system for transferring Dylan’s content to the new iPad mini. My main worry was accidentally deleting the copy of Ariel’s Beginnings I had gone to such lengths to

I did buy one, though not for me. The extra capacity and portability would be ideal for Dylan I decided: I could have his old iPad. So yesterday I rigged up a maybe-system for transferring Dylan’s content to the new iPad mini. My main worry was accidentally deleting the copy of Ariel’s Beginnings I had gone to such lengths to

This is not the post I had intended to make this week but, as is often the case, something happened. Ears: I’ve mentioned these before as Dylan has a habit of trying to remove them (other people’s not his own) when he is anxious. I hadn’t realised until this week, however, how useful ears can be.

This is not the post I had intended to make this week but, as is often the case, something happened. Ears: I’ve mentioned these before as Dylan has a habit of trying to remove them (other people’s not his own) when he is anxious. I hadn’t realised until this week, however, how useful ears can be. I cannot begin to describe how painful this is. There is something very delicate about the back of the ear where the fleshy part meets the skull. I try to keep my humour by calling myself Van Barrett and enjoying the opportunity the ear attacks afford for being creative with a scarf (bandage-style around my head). Sometimes the behaviour disappears for a while. Recently, for example, I have felt brave enough to wear earrings again and to not bother with a scarf. A couple of nights ago, however, I sustained a bad attack. Recording it in Dylan’s log before I went to bed, I noted it had been nearly a month since the previous incident. I have no idea why Dylan pulls ears but am increasingly of the view that there is no single trigger. I continue to think sugar may be implicated in this and I know that Dylan had some ‘banned’ items earlier in the week. I’m also persuaded, however, that the behaviour is a response to anxiety which, for Dylan, can have multiple causes.

I cannot begin to describe how painful this is. There is something very delicate about the back of the ear where the fleshy part meets the skull. I try to keep my humour by calling myself Van Barrett and enjoying the opportunity the ear attacks afford for being creative with a scarf (bandage-style around my head). Sometimes the behaviour disappears for a while. Recently, for example, I have felt brave enough to wear earrings again and to not bother with a scarf. A couple of nights ago, however, I sustained a bad attack. Recording it in Dylan’s log before I went to bed, I noted it had been nearly a month since the previous incident. I have no idea why Dylan pulls ears but am increasingly of the view that there is no single trigger. I continue to think sugar may be implicated in this and I know that Dylan had some ‘banned’ items earlier in the week. I’m also persuaded, however, that the behaviour is a response to anxiety which, for Dylan, can have multiple causes. In some ways I wasn’t surprised by the incident. At last, I thought to myself, here it comes: the reaction. For the last two weeks Dylan has been transitioning into the residential home where he is to live. The transition plan is gentle but has still involved Dylan being away from home overnight more than he is used to. Dylan’s time has been divided between his day centre and residential home and as staff from both settings have joined up, people have appeared out of context. On days when Dylan has been at the residential setting, his usual routine has been interrupted. However much care you take, and whatever support you put in place, this is an unsettling time.

In some ways I wasn’t surprised by the incident. At last, I thought to myself, here it comes: the reaction. For the last two weeks Dylan has been transitioning into the residential home where he is to live. The transition plan is gentle but has still involved Dylan being away from home overnight more than he is used to. Dylan’s time has been divided between his day centre and residential home and as staff from both settings have joined up, people have appeared out of context. On days when Dylan has been at the residential setting, his usual routine has been interrupted. However much care you take, and whatever support you put in place, this is an unsettling time. Speaking of signs, these may have something to do with the ear attack. Signs (and symbols even more so) are important to Dylan. One of the things I did last year, at the height of Dylan’s anxiety, was to set up a weekly board at home. Although he had managed without one previously I thought it might help Dylan make sense of life which, at that point, followed a complex pattern. It was probably one of the best practical things I’ve done for Dylan. Since then we have established a bedtime routine of talking through what will happen the next day using the symbols. When Dylan removes the next day’s symbols from his board, it is a sign that he has understood the shape of tomorrow. When Dylan started attending his day centre full time and had clearer routines, he was able to put the symbols for the week on the board himself on Sunday evenings. This not only helped Dylan make sense of his week, it created a sense of participation and ownership.

Speaking of signs, these may have something to do with the ear attack. Signs (and symbols even more so) are important to Dylan. One of the things I did last year, at the height of Dylan’s anxiety, was to set up a weekly board at home. Although he had managed without one previously I thought it might help Dylan make sense of life which, at that point, followed a complex pattern. It was probably one of the best practical things I’ve done for Dylan. Since then we have established a bedtime routine of talking through what will happen the next day using the symbols. When Dylan removes the next day’s symbols from his board, it is a sign that he has understood the shape of tomorrow. When Dylan started attending his day centre full time and had clearer routines, he was able to put the symbols for the week on the board himself on Sunday evenings. This not only helped Dylan make sense of his week, it created a sense of participation and ownership. Because of their importance in Dylan’s life I encouraged Dylan to take his symbols when he went to his new home for the first time a couple of weeks ago. That week Dylan was travelling between settings. Although he is usually very careful with his things, somehow the symbols went missing. I have hunted through pockets and bags and asked at Dylan’s day centre and residential home but they appear to have vanished completely. As well as symbols and pictures of activities I wasn’t sure Dylan recognised the symbol for, there were laminated photos of key people and places in Dylan’s life. Where, I wondered, was my photograph now? At least I will be smiling, still, I told myself.

Because of their importance in Dylan’s life I encouraged Dylan to take his symbols when he went to his new home for the first time a couple of weeks ago. That week Dylan was travelling between settings. Although he is usually very careful with his things, somehow the symbols went missing. I have hunted through pockets and bags and asked at Dylan’s day centre and residential home but they appear to have vanished completely. As well as symbols and pictures of activities I wasn’t sure Dylan recognised the symbol for, there were laminated photos of key people and places in Dylan’s life. Where, I wondered, was my photograph now? At least I will be smiling, still, I told myself.

me to something entirely incidental. Recently I have been irritated by my spectacles which have felt increasingly uncomfortable. Twice I have visited my optician to complain that they are badly fitted and require adjustment. Both times the receptionists have politely fiddled with them for me in an effort to oblige. Last week when I complained again, however, the receptionist told me that she really could not see what the problem was: they were correctly fitted. Perhaps, she suggested, I just had to get used to them?

me to something entirely incidental. Recently I have been irritated by my spectacles which have felt increasingly uncomfortable. Twice I have visited my optician to complain that they are badly fitted and require adjustment. Both times the receptionists have politely fiddled with them for me in an effort to oblige. Last week when I complained again, however, the receptionist told me that she really could not see what the problem was: they were correctly fitted. Perhaps, she suggested, I just had to get used to them?