In my last post I reflected on the challenge of caring for a vulnerable adult who lacks the capacity to understand lockdown. Dylan’s intellectual disability and autism mean that even in ‘normal’ times he engages in what could be considered socially inappropriate behaviour; in the context of a public health crisis, a lack of regard for social norms such as distancing can result in challenging rule breaks. In this post, I celebrate the fact that Dylan breaks the rules and rejoice in the unexpected places this can lead…

22nd March, 2020 (Mothering Sunday, UK, Ireland)

To tell this story I have to go back to Mother’s Day which this year fell on the Sunday after the start of lockdown. Dylan and I had been celebrating his 26th birthday in Durham the previous weekend but returned to the news that we were to stay at home other than to take exercise, shop for food, travel for essential work or provide care to vulnerable people. The trips and activities which had been scheduled for the week, and which Dylan was expecting to happen, could not go ahead.

To tell this story I have to go back to Mother’s Day which this year fell on the Sunday after the start of lockdown. Dylan and I had been celebrating his 26th birthday in Durham the previous weekend but returned to the news that we were to stay at home other than to take exercise, shop for food, travel for essential work or provide care to vulnerable people. The trips and activities which had been scheduled for the week, and which Dylan was expecting to happen, could not go ahead.

While staff at Dylan’s home threw themselves into designing lockdown activities for the residents, I tried to think of alternative activities for the up-coming weekend. As I would be providing care to a vulnerable person I could still see Dylan, but our planned outing to Renishaw Hall was out of the question. This is an annual routine which helps me with Mothering Sunday, a day I have found difficult since my mother died in May 2006. I enjoy receiving cards and gifts from my children but it doesn’t lessen the pain of not being able to see my own mother. In some ways it makes her absence more acute, now I am un-mothered.

Reservoir

Government guidelines allowed me to take Dylan for exercise somewhere local. I decided the best replacement for our cancelled trip was a reservoir walk, something Dylan enjoys and for which there are multiple options . As I considered their relative merits, however, I realised that Dylan tends to associate reservoirs with pubs. Agden and the Old Horns. Langsett and The Waggon & Horses. Underbank and the Mustard Pot. Redmires and The Three Merry Lads. Dale Dike and The Strines Inn. This could be problematic.

Government guidelines allowed me to take Dylan for exercise somewhere local. I decided the best replacement for our cancelled trip was a reservoir walk, something Dylan enjoys and for which there are multiple options . As I considered their relative merits, however, I realised that Dylan tends to associate reservoirs with pubs. Agden and the Old Horns. Langsett and The Waggon & Horses. Underbank and the Mustard Pot. Redmires and The Three Merry Lads. Dale Dike and The Strines Inn. This could be problematic.

I set off driving along the road between Dylan’s residential setting and my home, along which the reservoirs are scattered. ‘Renishaw is closed today, Dylan’ I told him. ‘Let’s walk around a reservoir instead.’ I was still wondering which one when, at a bend in the road, I remembered Broomhead. It isn’t a reservoir we visit, really. We walked around it three summers ago for the first time in years. There are no routines associated with it and there is no pub nearby. It also tends to be quieter than other reservoirs. Perfect for lockdown then.

I eyed Dylan through the rear-view mirror as I parked up. He was thinking about something I could tell, his face a blend of surprise and alert. Dylan and I set off walking anti-clockwise along the reservoir’s south bank. When we reached the cross-wall at the reservoir end, where I expected Dylan to turn left and head back by the north bank, he chose to walk on. Here, Broomhead Reservoir trickles into Morehall Reservoir like a tear. As we more often walk around Morehall, I assumed Dylan was hankering after a familiar landscape. There was probably enough time for us to walk around both reservoirs. ‘Alright Dylan’, I said.

But to my surprise Dylan made a wedge-shaped turn and doubled back on himself to the road which runs between the reservoirs, separating their two tears. He must be crossing to the opposite bank to walk our usual clockwise direction around Morehall, I thought to myself. I quite liked the idea of walking a figure of 8. But rather than make a right turn when we got to the other bank, Dylan turned left. So, he did want to walk around Broomhead? I looked at Dylan. He had a glint in his eye. There was, I suddenly realised, something looming up ahead.

Matriarch

As Dylan strode purposefully up the road I thought of her. How could I not? This is where my sister used to live, in a waterside house, off to the right, tucked in under ancient trees. Perhaps she still did? I hadn’t had any contact with my sister since our mother died . Across those 14 years, the weight of silence had become too heavy to carry and too much to break.

As Dylan strode purposefully up the road I thought of her. How could I not? This is where my sister used to live, in a waterside house, off to the right, tucked in under ancient trees. Perhaps she still did? I hadn’t had any contact with my sister since our mother died . Across those 14 years, the weight of silence had become too heavy to carry and too much to break.

Why? I don’t remember. The wrong word at the wrong time. A mistaken look. A misjudged silence. ‘Something and nothing’, as my mother used to say to us when we squabbled as children. The only thing I’m sure of, looking back, is that grief undoes people. It pulls the ground from under them. And it takes people in different ways at different rates. And in those desperate days we can say and do unthinking things. It is a painful unravelling. A wild reeling. A terrible scrabbling while the earth tilts.

After, as the estranged days became weeks then months then years, I wished there was someone to help fix things. Someone who would have understood it was because we were hurting. Someone who could have supported us through our stubborn silence. Someone who would have helped us to heal. What do you do when that person has gone? I didn’t realise, while she was alive, how responsible she was for holding the family together.

Dylan Remembering

When Dylan and I walked this way, three summers before, I had been aware of his gaze on the house beneath the ancient trees. Perhaps he gestured at it in the questioning way he has. I don’t know because I had turned my face to the ground, tightened my hold on Dylan’s arm, hurried him along. I remember feeling overwhelmed and anxious. What if she saw us?

When Dylan and I walked this way, three summers before, I had been aware of his gaze on the house beneath the ancient trees. Perhaps he gestured at it in the questioning way he has. I don’t know because I had turned my face to the ground, tightened my hold on Dylan’s arm, hurried him along. I remember feeling overwhelmed and anxious. What if she saw us?

Today, Dylan is ahead of me, gathering pace. As we draw level with the house in the woods I call his name softly, hold out my arm. Dylan ignores me and I call him again, more urgently: ‘Dylan! Dylan!’. But there is no stopping him this time. He is heading towards the house that he remembers. He is striding up the path at the side of the house, following the route he has always known. I call him more sharply: ‘Dylan! Come back Dylan!’ But he has crossed the back yard and is heading for the door.

What is he remembering? Family gatherings on Boxing Day. Cakes and biscuits and orange juice. An exercise bike in an upstairs room. A fire. Men with beards. His Gran. Watching films in a room with a big glass window. Escaping unnoticed upstairs while the big people talk and laugh. Riding pillion with me on his uncle’s motorbike along the private track (probably especially that). Who knows what Dylan remembers of those days.

I pick up pace. I must hoick Dylan back to the reservoir path. I need to restore the day to normal. I want to shout but don’t want to attract attention. ‘No, Dylan, no!’ I hiss at him. But it is too late. He is opening the door. Walking in. Not even knocking! Now he is in the house. I am outside, utterly at sea. Surely, it will swallow me? I poke my head around the door pleading: ‘Dylan come back.’ But he is on his knees in a corner, browsing DVDs. ‘I’m so sorry’ I say, as my sister and her husband appear. ‘I’m so sorry’. She takes me by my hands, looks into my eyes. ‘It’s alright’, she says. ‘It’s alright. Don’t worry.’

Healing Dylan

After 14 years it took Dylan to bring this reconciliation about. Only Dylan could have done this. It needed someone driven by feelings and desires – uninhibited by real or imagined hurts and slights, ungoverned by social rules or convention. After all these years of wondering whether a family wound could ever be healed and worrying that none of us would fix things, it was Dylan who made it better.

Bless Dylan. How I love that, in the end, it was this young man – whose autism and intellectual disability famously confer deficits of imagination, social understanding, empathy, cognitive capacity and communication – who brought this about. Blessings on my passionate, strong-willed, opportunistic son.

Breaking the Rules

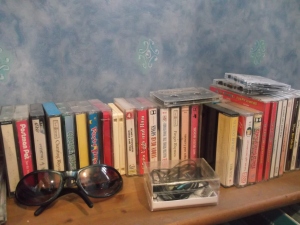

As the first weekend we would be in lockdown happened to coincide with Mother’s Day, Government briefings had particularly noted that the rules meant no contact with families. After 14 years of having had no contact, Dylan and I stayed a couple of hours with my sister and her husband. We spent the time chatting and drinking tea. Dylan gazed at an architectural drawing of the Natural History Museum and lobbied for chocolate biscuits. By the time we left he had explored every room in the house and helped himself to four DVDs. On our way out of the door, unprompted, Dylan extended his arm to his aunt and uncle in turn, shook them by the hand. ‘We’ve broken every rule in the book today’, I observed.

As the first weekend we would be in lockdown happened to coincide with Mother’s Day, Government briefings had particularly noted that the rules meant no contact with families. After 14 years of having had no contact, Dylan and I stayed a couple of hours with my sister and her husband. We spent the time chatting and drinking tea. Dylan gazed at an architectural drawing of the Natural History Museum and lobbied for chocolate biscuits. By the time we left he had explored every room in the house and helped himself to four DVDs. On our way out of the door, unprompted, Dylan extended his arm to his aunt and uncle in turn, shook them by the hand. ‘We’ve broken every rule in the book today’, I observed.

As Dylan and I made our way back to the car I was conscious of a slackening inside, a different relaxed. The light was warm and honey-coloured. We stopped once or twice and took photographs. Later, when I looked at the pictures on my phone, I was struck by the relief in my face. I texted my sister. ‘I am smiling at the news on the radio not to see family today.’ ‘I think we can just about make an exception in this case’ she replied. We marvelled at the circumstances that had reunited us and at the serendipity of it being Mother’s Day. ‘Mum will be smiling on us’, my sister reflected.

Since Mother’s Day, my sister and I have observed lockdown. We hope to meet again soon!

I’m always amazed by the way Dylan intuitively grasps new technologies. Even with his learning disability he is a Digi kid, understanding (unlike his mother) that devices need to be swiped not clicked.

I’m always amazed by the way Dylan intuitively grasps new technologies. Even with his learning disability he is a Digi kid, understanding (unlike his mother) that devices need to be swiped not clicked. My ex-husband remarried recently and my daughter and her half-sister were bridesmaids. Swiping through my iPhone photos the weekend after the wedding, Dylan froze, his finger hovering mid-air over a photo of the three of them (sent by my daughter via WhatsApp): ‘Daddy! Daddy!’ he shouted. I didn’t know what to say. I don’t have photos of my ex-husband around the house and Dylan hasn’t had more than fleeting contact with him since we divorced 15 years ago. I thought my heart would break.

My ex-husband remarried recently and my daughter and her half-sister were bridesmaids. Swiping through my iPhone photos the weekend after the wedding, Dylan froze, his finger hovering mid-air over a photo of the three of them (sent by my daughter via WhatsApp): ‘Daddy! Daddy!’ he shouted. I didn’t know what to say. I don’t have photos of my ex-husband around the house and Dylan hasn’t had more than fleeting contact with him since we divorced 15 years ago. I thought my heart would break. I think I knew really. I just didn’t want to admit it. I’ve written before about the way Dylan finds emotional release through music. How he loves Sting’s Fields of Gold (which his Daddy used to dance him around the room to). How he can’t bear to listen to U2s All That You Can’t Leave Behind (the soundtrack to my divorce). And now I remember the way Dylan would look at me with questions in his eyes when his Daddy called to collect just his sister at weekends and holidays.

I think I knew really. I just didn’t want to admit it. I’ve written before about the way Dylan finds emotional release through music. How he loves Sting’s Fields of Gold (which his Daddy used to dance him around the room to). How he can’t bear to listen to U2s All That You Can’t Leave Behind (the soundtrack to my divorce). And now I remember the way Dylan would look at me with questions in his eyes when his Daddy called to collect just his sister at weekends and holidays. I might not have realised how hard being a parent is but Dylan’s biological father had been clear about this. He was not prepared to co-parent another child he told me (he had two from a previous marriage and had not found parenthood easy). If I continued with the pregnancy, I’d be on my own.

I might not have realised how hard being a parent is but Dylan’s biological father had been clear about this. He was not prepared to co-parent another child he told me (he had two from a previous marriage and had not found parenthood easy). If I continued with the pregnancy, I’d be on my own. The photo of my daughter and her half-sister at their dad’s wedding arrived on the day Dylan and I headed south for our annual summer holiday. This year I had booked a cottage on the coast, selected for its proximity to the things which Dylan loves: beaches, steam trains, country walks, rivers, castles and cathedrals. I didn’t subconsciously choose it (did I?) because it lay within spitting distance of the college where his biological father and I had worked.

The photo of my daughter and her half-sister at their dad’s wedding arrived on the day Dylan and I headed south for our annual summer holiday. This year I had booked a cottage on the coast, selected for its proximity to the things which Dylan loves: beaches, steam trains, country walks, rivers, castles and cathedrals. I didn’t subconsciously choose it (did I?) because it lay within spitting distance of the college where his biological father and I had worked. So Dylan and I spent a half hour strolling around the college grounds in the blossomy hum of summer. There were a few new buildings but the place felt eerily familiar. “That is where mummy used to work” I told Dylan, pointing at a red brick house. “And here”, I added, “is where your daddy’s office was”. I photographed Dylan standing by the building, looking like his father.

So Dylan and I spent a half hour strolling around the college grounds in the blossomy hum of summer. There were a few new buildings but the place felt eerily familiar. “That is where mummy used to work” I told Dylan, pointing at a red brick house. “And here”, I added, “is where your daddy’s office was”. I photographed Dylan standing by the building, looking like his father.

Dylan missed being born on Mother’s Day, in 1994, by 21 minutes. “Hurry up”, the midwife said to me towards the end of my 72 hour labour “or you won’t get a mother’s day baby.” I wanted it to be over but I didn’t give a fig about Mother’s Day. In more than 30 years, I’d given my mother no more than a handful of cards to mark the day. I wasn’t the sort of person who cared about such things.

Dylan missed being born on Mother’s Day, in 1994, by 21 minutes. “Hurry up”, the midwife said to me towards the end of my 72 hour labour “or you won’t get a mother’s day baby.” I wanted it to be over but I didn’t give a fig about Mother’s Day. In more than 30 years, I’d given my mother no more than a handful of cards to mark the day. I wasn’t the sort of person who cared about such things. Dylan and I drove to Brighton on Mother’s Day to celebrate his 24th birthday. We hadn’t been back since we left when Dylan was six months old but this year things fell auspiciously for a return visit to the town where he was born.

Dylan and I drove to Brighton on Mother’s Day to celebrate his 24th birthday. We hadn’t been back since we left when Dylan was six months old but this year things fell auspiciously for a return visit to the town where he was born. What I hadn’t bargained for was my mother. I didn’t connect her with the trip at all but as soon as we arrived I was ambushed by memories. Although she and I hadn’t been particularly close, mum stayed in Brighton with me after Dylan was born. This wasn’t planned; she had only meant to visit while her first grandchild made its arrival. But I didn’t have a clue how to look after the baby and when she realised this mum asked for leave from her job in a school so she could stay on for a couple of weeks.

What I hadn’t bargained for was my mother. I didn’t connect her with the trip at all but as soon as we arrived I was ambushed by memories. Although she and I hadn’t been particularly close, mum stayed in Brighton with me after Dylan was born. This wasn’t planned; she had only meant to visit while her first grandchild made its arrival. But I didn’t have a clue how to look after the baby and when she realised this mum asked for leave from her job in a school so she could stay on for a couple of weeks. I had taken ‘Baby’s First Photo Album’ to Brighton hoping it might help me to explain to Dylan that we had once lived there. I’m not sure Dylan understands that he is the baby in the photographs or, indeed, that he was once a baby himself. Babies hold a special terror for Dylan; he hates the sound of them crying and is made very anxious by their presence. So Dylan has not really been interested in looking at photo records of his early life. Knowing Dylan’s interest in matching images, however, I thought he might pay attention if I could recreate the photographs while we were there.

I had taken ‘Baby’s First Photo Album’ to Brighton hoping it might help me to explain to Dylan that we had once lived there. I’m not sure Dylan understands that he is the baby in the photographs or, indeed, that he was once a baby himself. Babies hold a special terror for Dylan; he hates the sound of them crying and is made very anxious by their presence. So Dylan has not really been interested in looking at photo records of his early life. Knowing Dylan’s interest in matching images, however, I thought he might pay attention if I could recreate the photographs while we were there. “I have become my mother” I said to my friend R over coffee next day. I’d suggested meeting a poet friend and his partner for a walk while Dylan and I were in town. It was a cold, wet day and we’d retreated to a cafe for coffee and cake. “I wear my hair longer than she kept hers but otherwise we look the same, right down to our coats of green”. OK, mine is lime and hers was emerald. But even so…

“I have become my mother” I said to my friend R over coffee next day. I’d suggested meeting a poet friend and his partner for a walk while Dylan and I were in town. It was a cold, wet day and we’d retreated to a cafe for coffee and cake. “I wear my hair longer than she kept hers but otherwise we look the same, right down to our coats of green”. OK, mine is lime and hers was emerald. But even so… “Smile, Dylan” I said. “Let mummy take just one more”. Dylan grimaced at me in the rain. I put my arms together and rocked them. “When you were a baby”, I said, “this is where mummy and Dylan lived. Mummy and Dylan the baby lived here in this house”. I pointed up at my top floor flat. It looked shabbier than I remembered but just as lovely. “We were very happy here”, I told Dylan. “And your Gran stayed with us and helped mummy to look after you.” Dylan tugged at me. It was past lunch time…

“Smile, Dylan” I said. “Let mummy take just one more”. Dylan grimaced at me in the rain. I put my arms together and rocked them. “When you were a baby”, I said, “this is where mummy and Dylan lived. Mummy and Dylan the baby lived here in this house”. I pointed up at my top floor flat. It looked shabbier than I remembered but just as lovely. “We were very happy here”, I told Dylan. “And your Gran stayed with us and helped mummy to look after you.” Dylan tugged at me. It was past lunch time… Caring for Dylan is as natural, now, as breathing. My mum taught me how to look after a new born baby and I learned, from Dylan, how to take care of my autistic son. Our six months in Brighton, 24 years ago, seemed suddenly unreal; I had been in a bubble then, my eyes fixed on a thin blue line between sea and sky. Today, I couldn’t even see the horizon. I wanted to cry but I said “Dylan, let’s buy an umbrella then go and find E.”

Caring for Dylan is as natural, now, as breathing. My mum taught me how to look after a new born baby and I learned, from Dylan, how to take care of my autistic son. Our six months in Brighton, 24 years ago, seemed suddenly unreal; I had been in a bubble then, my eyes fixed on a thin blue line between sea and sky. Today, I couldn’t even see the horizon. I wanted to cry but I said “Dylan, let’s buy an umbrella then go and find E.” The next morning is the bluest of blues. After breakfast we walk down to the beach. The thin line at the edge of the world is so clear I imagine the ships could tumble off. I watch Dylan throw stones into the sea. He concentrates hard on this for 40 minutes, testing the arc of his arm against the waves. I read some poems, try to make out the avenue where we lived, away in the distance. I think of mum and Dylan and feel part of a chain, a piece of their history.

The next morning is the bluest of blues. After breakfast we walk down to the beach. The thin line at the edge of the world is so clear I imagine the ships could tumble off. I watch Dylan throw stones into the sea. He concentrates hard on this for 40 minutes, testing the arc of his arm against the waves. I read some poems, try to make out the avenue where we lived, away in the distance. I think of mum and Dylan and feel part of a chain, a piece of their history.

Although Dylan has been walking the valley virtually all his life, since we lived close by he has developed fixed routines. Occasionally Dylan will adjust his route or add something new. Recently, for example, he decided we have to climb some steps and add a spur to the outward journey; I think this is so we can pass by three cottages Dylan has developed an interest in. I’m usually pleased when Dylan decides to change his routine but today I wasn’t sure his proposed adjustment could be considered a ‘development’.

Although Dylan has been walking the valley virtually all his life, since we lived close by he has developed fixed routines. Occasionally Dylan will adjust his route or add something new. Recently, for example, he decided we have to climb some steps and add a spur to the outward journey; I think this is so we can pass by three cottages Dylan has developed an interest in. I’m usually pleased when Dylan decides to change his routine but today I wasn’t sure his proposed adjustment could be considered a ‘development’.