I’m happy to report that Dylan has continued seizure-free. This suggests the medication he has been prescribed is a good starting point for managing the epilepsy. Equally, the absence of episodes could be linked to the fact that Dylan has been able to resume some of his regular activities. Certainly, he seems to be less stressed than he was a year ago. In this blog I share some Christmas updates and reflect on the continuing impact of coronavirus on Dylan.

Canaries

Coal miners carried caged canaries into underground tunnels as the birds would alert them to the presence of noxious gases. I think of Dylan as a sort of ‘pit canary’ for the environments we have to negotiate in our daily lives. If a place or situation triggers ‘behaviours’ in him then It might suggest that there is something stressful about the circumstances which could potentially unsettle any of us.

Coal miners carried caged canaries into underground tunnels as the birds would alert them to the presence of noxious gases. I think of Dylan as a sort of ‘pit canary’ for the environments we have to negotiate in our daily lives. If a place or situation triggers ‘behaviours’ in him then It might suggest that there is something stressful about the circumstances which could potentially unsettle any of us.

Dylan has no ‘filter’ so if he finds an environment uncomfortable or threatening he will express his feelings through behaviours ranging from mild (jumping and pacing), to moderate (smashing or ripping) or extreme (hurting himself or others). Those of us who are not autistic and learning disabled know that it is not acceptable to bite someone or smash crockery but it doesn’t mean we experience the world as any less stressful than Dylan. I’d hazard I’m not alone in having felt like smashing a few plates over the last couple of years.

Living in the age of pandemic will be taking a toll on all of us. Observing Dylan’s unfiltered physical and emotional reactions to the environment leads me to reflect on the impact of managing our stress and anxiety through internalising rather than externalising behaviours. Perhaps someone should set up jumping, tearing and plate-smashing arenas where we can self-regulate as Dylan does.

Testing Times

Speaking of Arenas, I was relieved to be able to take Dylan to his beloved Disney-on-Ice at Sheffield Arena last month. It’s become an annual Christmas tradition for Dylan and one that he missed terribly in 2020 when it was cancelled due to Covid-19. I optimistically bought tickets for this year’s show and crossed my skates that it would go ahead.

Speaking of Arenas, I was relieved to be able to take Dylan to his beloved Disney-on-Ice at Sheffield Arena last month. It’s become an annual Christmas tradition for Dylan and one that he missed terribly in 2020 when it was cancelled due to Covid-19. I optimistically bought tickets for this year’s show and crossed my skates that it would go ahead.

On the run-up to the performance all seemed well so we included it on Dylan’s programme and allowed him to feel the anticipation he experiences so intensely. To my dismay, just days before Dylan was due to attend the show, new regulations meant that all ticket holders would have to provide proof of C-19 vaccination or a negative Lateral Flow Test (LFT). Dylan has refused all attempts at vaccination and we had never attempted to test him for C-19, assuming he would not consent to a process which is physically invasive and can be experienced as distressing. I was beside myself. What to do? I dreaded the meltdown that would ensue if I told Dylan that Disney-on-Ice was ‘closed’ after all.

I received daily texts from the venue reminding ticket-holders of the requirement to provide proof of Covid-19 status and including additional guidelines such as the need for an LFT to have been reported and notified to a mobile phone. A test kit showing a negative result would not be acceptable. Part of me was concerned that this new world was one from which Dylan (and those like him) would be excluded. Having spent the last few months returning to his regular activities, would Dylan now find himself locked out of some of the things he likes to do because his disability means he can’t provide the necessary documentation? The other part of me was determined to get him in.

The only option seemed to be to persuade Dylan to cooperate with an LFT. So, a week before the event I got Dylan to watch me testing myself and to copy everything I did. To my surprise he was quite comfortable swabbing the back of his throat – more reluctant to insert the swab in his nose but able to do enough to get a valid reading. This was an exciting breakthrough. If we could test Dylan regularly this would not only open up opportunities for activities but enable informed decisions about managing Dylan’s health care.

On the day of the performance I was nervous about whether Dylan would be willing to take a test for a second time but he cooperated beautifully. This was not the end of my anxiety about getting Dylan into Disney-on-Ice that evening, however. Having reported Dylan’s negative result in the afternoon, it had still not been notified to my phone by the time of the show. I tried reporting again, and the care home submitted an additional report, but still nothing. I was a bag of nerves, checking my phone and thinking how terrible it would be if having encouraged Dylan to cooperate with the testing process he was denied admission. To my huge relief, however, Covid-19 status wasn’t checked at the gates that evening.

Notification of Dylan’s test result was finally delivered to my phone five hours after I reported. I guess on a Friday night the system was log-jammed with people like us, needing proof of a negative LFT. The stress and anxiety I experienced getting Dylan into the Arena were worth it, however. Dylan spent the performance on the edge of his seat, clapping enthusiastically (in appropriate places) especially for his beloved Ariel and the clock and candlestick in Beauty and the Beast. It was lovely to see him so happy. It’s great that we can now test Dylan regularly and the experience has reminded me not to assume that Dylan won’t do something until I’ve tried everything, including authentic motivators such as admission to Disney-on-Ice.

Back to the Moon

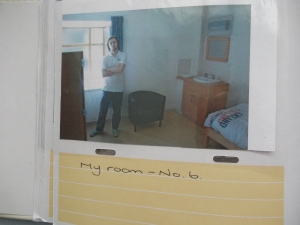

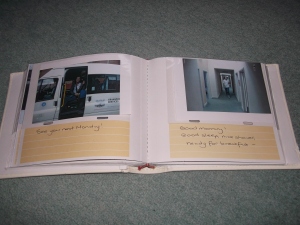

Dylan has continued to enjoy the resumption of his overnight stays at the moon (aka Premier Inn). One of the benefits of my having retired is that I now have the flexibility to support Dylan during the week as well as at weekends. This means I can look for the cheapest night on offer at his beloved ‘moon hotels’ instead of having to pay high rates at peak times. The savings are so dramatic I’ve decided it is perfectly reasonable for Dylan to make a trip to a moon once a month.

In November Dylan thoroughly enjoyed an overnight stay at the Premier Inn in Cleethorpes. We have visited the resort regularly as it’s the closest coast to our home city but we have never stayed overnight. On previous day trips, Dylan has pushed and pulled and cajoled me to the Premier Inn so that he can stand and gaze at it. He was needless to say in high excitement that this time he got to go inside (with a pumpkin lantern and Doctor Who).

In November Dylan thoroughly enjoyed an overnight stay at the Premier Inn in Cleethorpes. We have visited the resort regularly as it’s the closest coast to our home city but we have never stayed overnight. On previous day trips, Dylan has pushed and pulled and cajoled me to the Premier Inn so that he can stand and gaze at it. He was needless to say in high excitement that this time he got to go inside (with a pumpkin lantern and Doctor Who).

For December I had booked a stay in one of the Premier Inns in Chester, to coincide with a visit to see the Christmas Lanterns at Chester Zoo. Storm Arwen scuppered our plans, however, with the Zoo having to close its gates in order to clear the debris and the Pass over the Pennines too treacherous to risk. I figured Dylan would cope with the cancellation of the Zoo trip but not with the disappointment of no moon. In a moment of inspiration I booked a night at our local Premier Inn as replacement. It’s a high-rise hotel which we drive-by every week and which Dylan has rubbernecked for years: ‘moon, moon’ he shouts. The storm might have interrupted travel but it wouldn’t stop us walking three miles …

Dylan and I had a marvellous night. I had asked to be allocated a room on the top floor. Dylan was mesmerised by the view and enjoyed picking out familiar places. We spent an evening being tourists in our home city, riding the Christmas carousel and dining out. What I learned from this is that the highlight of our trips for Dylan is staying at a moon hotel – he’s as happy three miles as 103 miles away from home. Still, I re-booked the Chester Lanterns after the storm had passed: two moons in December for Dylan!

First Christmas

After Dylan helped me decorate our Christmas tree one weekend it occurred to me he would probably enjoy decorating his own flat. Any 27-year old spending their first Christmas in their own place would surely love that. Jay, who coordinates the social enterprise at Dylan’s residential home, supported Dylan to choose a tree and make his own decorations and trimmings for the walls. Dylan’s flat looks fabulous. I especially like the paper chains. This is the sort of thing about Dylan’s life which makes me smile.

Dylan came home for the Christmas holiday. I decided not to take him to visit my Dad, who isn’t well, but we saw my sister and enjoyed winter walks, good food and favourite films.

Another Covid Year

As the year turns, my concern for the future is not so much the threat of the virus to Dylan as its impact on his quality of life. Dylan is young and fit and if he does contract C-19 there is every reason to believe he would cope with the infection. The current regulations around testing and isolation, however, are causing chronic staff shortages in the care sector, including at Dylan’s setting. This is a situation which poses a range of challenges and risks for staff and residents, especially in the context of adults with intellectual disability and autism.

By way of illustration, some of the consequences of staff shortages for Dylan include the cancellation of trips and activities; inability to support with some personal care routines (such as shaving); reduction of supervision at key times of day; and the need for Dylan to spend additional nights with me. Fortunately, I am able to support with this (again, thanks to my having retired) but it’s not a satisfactory or sustainable solution to caring for a vulnerable adult with complex needs. Dylan and other adults like him require high levels of staffing in order to maintain the routines and activities which promote their health and well-being, particularly in relation to managing anxiety. I fear that the current situation leaves Dylan vulnerable to stress and therefore at risk of further epileptic episodes.

I suspect the issue of staffing in care homes is going to be a key challenge in 2022. While the regulations around the management of C-19 is creating the current crisis in staffing, the reality is that it has always been difficult to recruit and retain care workers. If the present situation leads to a review of employment pay and conditions in the care sector, then that will be a silver lining from yet another Covid cloud. Here’s hoping for better times ahead.

Thank you for following our blog in 2021

Health and Happiness in 2022

Dylan is in the habit of greeting people with a hand shake while out and about in the community. He doesn’t take the hand of every passing stranger, and he doesn’t do this every time he goes out, but if he sees someone he likes the look of he will extend a hand.

Dylan is in the habit of greeting people with a hand shake while out and about in the community. He doesn’t take the hand of every passing stranger, and he doesn’t do this every time he goes out, but if he sees someone he likes the look of he will extend a hand. After the trip to Bakewell I suggested to staff at Dylan’s care home that he wear gloves on trips out. That should reassure the public, I thought. More importantly, someone pointed out to me, it would protect Dylan. While Dylan wouldn’t choose to put gloves on, he is quite happy to wear a pair if he is given them. That’s a lucky thing, I thought to myself.

After the trip to Bakewell I suggested to staff at Dylan’s care home that he wear gloves on trips out. That should reassure the public, I thought. More importantly, someone pointed out to me, it would protect Dylan. While Dylan wouldn’t choose to put gloves on, he is quite happy to wear a pair if he is given them. That’s a lucky thing, I thought to myself. As February gave way to March I turned my attention to plans for Dylan’s birthday. As well as a weekly programme Dylan has a monthly countdown chart and for weeks Dylan had been ‘asking’ when his birthday would appear. Dylan had been promised a trip, by train, to his beloved Durham and an overnight stay in his hotel chain of choice (Premier Inn). I had already booked the tickets and accommodation and on weekend visits home Dylan would check the documents were still on my desk and ask ‘Deeham? Bur?’

As February gave way to March I turned my attention to plans for Dylan’s birthday. As well as a weekly programme Dylan has a monthly countdown chart and for weeks Dylan had been ‘asking’ when his birthday would appear. Dylan had been promised a trip, by train, to his beloved Durham and an overnight stay in his hotel chain of choice (Premier Inn). I had already booked the tickets and accommodation and on weekend visits home Dylan would check the documents were still on my desk and ask ‘Deeham? Bur?’ I wondered if I could persuade Dylan to wear a face mask. I trialled two versions: dust masks from the local hardware store and medical masks from Dylan’s care home. Not only would Dylan not accept either of them, he wouldn’t let me wear one either. This may be because the

I wondered if I could persuade Dylan to wear a face mask. I trialled two versions: dust masks from the local hardware store and medical masks from Dylan’s care home. Not only would Dylan not accept either of them, he wouldn’t let me wear one either. This may be because the  My anxieties about the journey proved unfounded and we arrived without incident. As well as an emergency kit I had packed candles and matches as the first activity on Dylan’s programme was to buy a birthday cake. We called at a supermarket on our way to the hotel. Dylan chose a Peppa Pig cake (I would never have got that right if I’d bought it in advance).

My anxieties about the journey proved unfounded and we arrived without incident. As well as an emergency kit I had packed candles and matches as the first activity on Dylan’s programme was to buy a birthday cake. We called at a supermarket on our way to the hotel. Dylan chose a Peppa Pig cake (I would never have got that right if I’d bought it in advance). Dylan re-traced a familiar route through the city but there were changes since our last visit. Dylan’s favourite café had been re-branded and now sells Thai food. Dylan had been talking about the potato with butter and cheese he was planning to order for his lunch since we planned the trip and I felt my sharp intake of breath as I steeled myself for Dylan’s reaction. And is it the magic of being 26 that means Dylan can shrug this off, accept my proposal of the Cathedral café for lunch instead?

Dylan re-traced a familiar route through the city but there were changes since our last visit. Dylan’s favourite café had been re-branded and now sells Thai food. Dylan had been talking about the potato with butter and cheese he was planning to order for his lunch since we planned the trip and I felt my sharp intake of breath as I steeled myself for Dylan’s reaction. And is it the magic of being 26 that means Dylan can shrug this off, accept my proposal of the Cathedral café for lunch instead? After years of renovation, the Cathedral tower had re-opened. Dylan chose to climb the 325 steps to the roof where he edged gingerly around the railings saying ‘whoops’. Inside, the university orchestra were rehearsing for a performance of Bruckner’s 4th Symphony. After our trip up the tower, Dylan and I sat for a while. A birthday blessing.

After years of renovation, the Cathedral tower had re-opened. Dylan chose to climb the 325 steps to the roof where he edged gingerly around the railings saying ‘whoops’. Inside, the university orchestra were rehearsing for a performance of Bruckner’s 4th Symphony. After our trip up the tower, Dylan and I sat for a while. A birthday blessing. The next day, over breakfast, I checked the local attractions. Apart from the Castle, everything appeared to be open as normal. I suggested to Dylan that we take a walk around Wharton Park which we hadn’t visited before. From the Battery above the railway station we watched people waiting for the Plymouth train. I tried to count the peals of bells ringing out across the city. We walked down Sidegate to Crook Hall where the maze had thickened since our last visit. Dylan checked all the dead-ends before heading to the café for lunch.

The next day, over breakfast, I checked the local attractions. Apart from the Castle, everything appeared to be open as normal. I suggested to Dylan that we take a walk around Wharton Park which we hadn’t visited before. From the Battery above the railway station we watched people waiting for the Plymouth train. I tried to count the peals of bells ringing out across the city. We walked down Sidegate to Crook Hall where the maze had thickened since our last visit. Dylan checked all the dead-ends before heading to the café for lunch. The departing students and disappearing paracetamol were the only signs that we were on the cusp of change that weekend. An ‘essential journeys only’ directive was issued the day after we got home. The next day, the university where I work moved all teaching online. The following day, confirmed cases of Covid-19 in Sheffield reached 36. By the end of the week the schools had closed. At the weekend we were asked (and, when the public disobeyed, subsequently told) to stay indoors. Dylan’s birthday trip had turned out to be a last gasp before the collective intake of breath.

The departing students and disappearing paracetamol were the only signs that we were on the cusp of change that weekend. An ‘essential journeys only’ directive was issued the day after we got home. The next day, the university where I work moved all teaching online. The following day, confirmed cases of Covid-19 in Sheffield reached 36. By the end of the week the schools had closed. At the weekend we were asked (and, when the public disobeyed, subsequently told) to stay indoors. Dylan’s birthday trip had turned out to be a last gasp before the collective intake of breath. Dylan and I usually go away twice a year, at Easter and during the Summer. For the first time ever, we didn’t have a holiday at Easter this year. I wasn’t sure whether Dylan would notice but he was clearly disappointed. Although time is not an easy concept for Dylan he makes associations with key events through the year and keeps track of it. So when I gave Dylan his Easter Egg he looked at me and said ‘cot’ quizzically. He was, I realised, asking me when we would be setting off to a holiday cottage. ‘Not this year, Dylan’ I said. ‘Boat?’ he asked, hopefully.

Dylan and I usually go away twice a year, at Easter and during the Summer. For the first time ever, we didn’t have a holiday at Easter this year. I wasn’t sure whether Dylan would notice but he was clearly disappointed. Although time is not an easy concept for Dylan he makes associations with key events through the year and keeps track of it. So when I gave Dylan his Easter Egg he looked at me and said ‘cot’ quizzically. He was, I realised, asking me when we would be setting off to a holiday cottage. ‘Not this year, Dylan’ I said. ‘Boat?’ he asked, hopefully. never again to stay in a Premier Inn, I decided this trip would be a good opportunity to try and extend Dylan’s repertoire.

never again to stay in a Premier Inn, I decided this trip would be a good opportunity to try and extend Dylan’s repertoire. Staff at Dylan’s care home suggested that I show Dylan the hotel website and include a photo of it on his programme. This seemed to go well. The pool, in particular, captured Dylan’s attention and was the thing he talked about on the run-up to the trip; when he pointed to the photo of the hotel on his programme, the words he said were ‘pool’ and ‘swim’ rather than ‘bed’ and ‘moon’. So I set off for Durham optimistically, fairly confident we had prepared Dylan for the change of routine.

Staff at Dylan’s care home suggested that I show Dylan the hotel website and include a photo of it on his programme. This seemed to go well. The pool, in particular, captured Dylan’s attention and was the thing he talked about on the run-up to the trip; when he pointed to the photo of the hotel on his programme, the words he said were ‘pool’ and ‘swim’ rather than ‘bed’ and ‘moon’. So I set off for Durham optimistically, fairly confident we had prepared Dylan for the change of routine. In my experience such requests are frequently ignored; I have often had to return to reception to ask for an alternative room. As for adding a note about dietary requirements (I am vegan) I have wondered why I bother. So I was amazed, on arrival at the hotel, to find that we had been upgraded to a family room (lots of space) overlooking the River Wear and that there was a jug of soya milk in the room. Dylan seemed to enjoy the space and the view from the window!

In my experience such requests are frequently ignored; I have often had to return to reception to ask for an alternative room. As for adding a note about dietary requirements (I am vegan) I have wondered why I bother. So I was amazed, on arrival at the hotel, to find that we had been upgraded to a family room (lots of space) overlooking the River Wear and that there was a jug of soya milk in the room. Dylan seemed to enjoy the space and the view from the window! I had assumed that staying at a different hotel would be challenging for Dylan and that it would be important to maintain his other routines while we were in Durham. However, breaking the Moon habit seemed to loosen Dylan’s patterns more generally. So instead of having lunch in our usual café on Saturday we tried a different place. I was thrilled; the vegan options were much better and Dylan caught the spirit of adventure and had a Panini. I am guessing this was a positive experience because he accepted a different café again the next day.

I had assumed that staying at a different hotel would be challenging for Dylan and that it would be important to maintain his other routines while we were in Durham. However, breaking the Moon habit seemed to loosen Dylan’s patterns more generally. So instead of having lunch in our usual café on Saturday we tried a different place. I was thrilled; the vegan options were much better and Dylan caught the spirit of adventure and had a Panini. I am guessing this was a positive experience because he accepted a different café again the next day. I will be interested to see if Dylan builds some of these places into a revised repertoire next time we are in Durham. Another visit might not involve the same hotel – although we got a good deal on the booking it was more expensive than usual and I don’t want Dylan to grow too accustomed to such facilities 🙂 However, I now have the confidence to try something different again if need be.

I will be interested to see if Dylan builds some of these places into a revised repertoire next time we are in Durham. Another visit might not involve the same hotel – although we got a good deal on the booking it was more expensive than usual and I don’t want Dylan to grow too accustomed to such facilities 🙂 However, I now have the confidence to try something different again if need be.

Before I had my own family I used to say that for every child I gave birth to I would adopt another. This seemed a small but realistic way of balancing the desire to have a biological child with the desperate need of already-born children for a family.

Before I had my own family I used to say that for every child I gave birth to I would adopt another. This seemed a small but realistic way of balancing the desire to have a biological child with the desperate need of already-born children for a family. I remember making the case for collective child rearing in an undergraduate seminar in the early 80s. I can’t imagine how we got on to the topic but perhaps the discussion arose from the study of a political thinker. Rousseau maybe or Dewey. I’m not sure. What I do remember, though, is that I was a lone voice that day. After arguing valiantly but without effect I turned to Dr Robinson and appealed for his support against my peers. But he wouldn’t give it; having children, he told me, was not motivated by a will to improve society but by the desire to perpetuate the self.

I remember making the case for collective child rearing in an undergraduate seminar in the early 80s. I can’t imagine how we got on to the topic but perhaps the discussion arose from the study of a political thinker. Rousseau maybe or Dewey. I’m not sure. What I do remember, though, is that I was a lone voice that day. After arguing valiantly but without effect I turned to Dr Robinson and appealed for his support against my peers. But he wouldn’t give it; having children, he told me, was not motivated by a will to improve society but by the desire to perpetuate the self. To make a call for help at 3am in the night you have to be desperate and my friends were not – they were simply new parents dealing with the usual demands of a not-unusually unsettled baby. A desperate night is one when you are scraping poo off the walls yet again (I haven’t done that for years but will never forget when I had to, repeatedly). It is when you have lain next to your screaming child for five hours and they are still screaming. It is when you fall down the stairs because you are dog-tired from weeks of being up all night. It is when you drive 100 miles in darkness trying to settle your crying child. It is when you sit in the garden or barricade yourself in your room because you fear you will be hurt by your anxious son whose needs you have failed to understand well enough to help and who is in meltdown, a danger to you and to himself. It is when the house finally falls silent and you go to bed and cry yourself to sleep because you couldn’t be better or make a difference. It is when you stay up all night googling for answers or writing long letters, asking for help, which you know you will never send.

To make a call for help at 3am in the night you have to be desperate and my friends were not – they were simply new parents dealing with the usual demands of a not-unusually unsettled baby. A desperate night is one when you are scraping poo off the walls yet again (I haven’t done that for years but will never forget when I had to, repeatedly). It is when you have lain next to your screaming child for five hours and they are still screaming. It is when you fall down the stairs because you are dog-tired from weeks of being up all night. It is when you drive 100 miles in darkness trying to settle your crying child. It is when you sit in the garden or barricade yourself in your room because you fear you will be hurt by your anxious son whose needs you have failed to understand well enough to help and who is in meltdown, a danger to you and to himself. It is when the house finally falls silent and you go to bed and cry yourself to sleep because you couldn’t be better or make a difference. It is when you stay up all night googling for answers or writing long letters, asking for help, which you know you will never send. The Humber Bridge is a beautiful bridge over a wide river in the east of the county where I live. But in 2006 the way I would think and feel about that bridge changed forever when a mother and her autistic son climbed over the railings and down onto the underbelly of the bridge and jumped.

The Humber Bridge is a beautiful bridge over a wide river in the east of the county where I live. But in 2006 the way I would think and feel about that bridge changed forever when a mother and her autistic son climbed over the railings and down onto the underbelly of the bridge and jumped. Sadly there have been similar cases, often involving mothers who had appeared to be coping. I have listened to people express astonishment at such tragedies and suggest that had they only known they would have helped. I remember reading a request by one woman, in the aftermath of a similar case in America, that mothers bring their autistic children to her, rather than kill them, ‘in the middle of the night if need be’.

Sadly there have been similar cases, often involving mothers who had appeared to be coping. I have listened to people express astonishment at such tragedies and suggest that had they only known they would have helped. I remember reading a request by one woman, in the aftermath of a similar case in America, that mothers bring their autistic children to her, rather than kill them, ‘in the middle of the night if need be’.  Later, in August, the coroner would refer to Alison Davies’ ‘life of despair’. Although she was struggling to cope with her son’s increasingly violent attacks, Alison was determined that Ryan should not be taken into care. ‘She loved Ryan so much and she tried so hard; her bank of resilience had been depleted ‘, her family said in a statement following the inquest. Alison was, they added, ‘a wonderful mother’.

Later, in August, the coroner would refer to Alison Davies’ ‘life of despair’. Although she was struggling to cope with her son’s increasingly violent attacks, Alison was determined that Ryan should not be taken into care. ‘She loved Ryan so much and she tried so hard; her bank of resilience had been depleted ‘, her family said in a statement following the inquest. Alison was, they added, ‘a wonderful mother’. In the US, where there have been similar cases, there has been much discussion in the press and much condemnation of the mothers on social media. I understand this response but worry that a backlash against individuals obscures the spotlight from shining, as I believe it must, on all of us. I am not questioning that Ryan was unlawfully killed. Nor am I suggesting that Alison’s actions could ever be justified or excused. I do believe, however, that we are all involved in these tragic deaths because, in a civilized society, caring for vulnerable children and adults is a responsibility we share.

In the US, where there have been similar cases, there has been much discussion in the press and much condemnation of the mothers on social media. I understand this response but worry that a backlash against individuals obscures the spotlight from shining, as I believe it must, on all of us. I am not questioning that Ryan was unlawfully killed. Nor am I suggesting that Alison’s actions could ever be justified or excused. I do believe, however, that we are all involved in these tragic deaths because, in a civilized society, caring for vulnerable children and adults is a responsibility we share. I think this might be the last lap. At least I hope so: I’m not sure I have any reserves left for what has been a two year marathon. Since Dylan left school it has been a frustrating time of dead ends and disappointments. I have coped this far but am exhausted; if the finishing post moves one more time I doubt I could manage another lap.

I think this might be the last lap. At least I hope so: I’m not sure I have any reserves left for what has been a two year marathon. Since Dylan left school it has been a frustrating time of dead ends and disappointments. I have coped this far but am exhausted; if the finishing post moves one more time I doubt I could manage another lap. If you’ve been following

If you’ve been following  Unfortunately for Dylan the changes in his behaviour triggered further changes. Although one care setting has provided on-going support, other providers (including Dylan’s respite setting) felt unable to, given the changes in Dylan’s behaviour. Following a

Unfortunately for Dylan the changes in his behaviour triggered further changes. Although one care setting has provided on-going support, other providers (including Dylan’s respite setting) felt unable to, given the changes in Dylan’s behaviour. Following a  It’s not an easy road to be on if you are in crisis. Even when a setting has been identified the process of assessment and transition takes time. Something that has made these months particularly hard is the loss of Dylan’s respite. At the point at which I was in need of more support I got less. In fact I got nothing. I have written

It’s not an easy road to be on if you are in crisis. Even when a setting has been identified the process of assessment and transition takes time. Something that has made these months particularly hard is the loss of Dylan’s respite. At the point at which I was in need of more support I got less. In fact I got nothing. I have written  Dylan’s anxiety has been acute in the last few weeks and his aggressive behaviour has escalated. I have gone on trying to identify triggers but can’t always predict or head off incidents. I am no match for Dylan physically (21 and more than six foot tall, fit and strong) and after being hurt on a number of occasions I have learned to prioritise keeping myself safe. Recently, I have spent a lot of time in the garden where I go, now, to sit and wait until Dylan has calmed down. Sometimes it is five minutes, sometimes 50. Sometimes I am barefoot, sometimes better prepared. Sometimes it is fine, sometimes raining. Sometimes it is light, sometimes dark. Always I wait with my heart in my mouth for it to be over, praying that Dylan doesn’t hurt himself.

Dylan’s anxiety has been acute in the last few weeks and his aggressive behaviour has escalated. I have gone on trying to identify triggers but can’t always predict or head off incidents. I am no match for Dylan physically (21 and more than six foot tall, fit and strong) and after being hurt on a number of occasions I have learned to prioritise keeping myself safe. Recently, I have spent a lot of time in the garden where I go, now, to sit and wait until Dylan has calmed down. Sometimes it is five minutes, sometimes 50. Sometimes I am barefoot, sometimes better prepared. Sometimes it is fine, sometimes raining. Sometimes it is light, sometimes dark. Always I wait with my heart in my mouth for it to be over, praying that Dylan doesn’t hurt himself. It took quite a lot for me to admit that I couldn’t keep Dylan safe anymore. Some people have suggested that I might get more support with Dylan if I didn’t appear to cope so well. You appear too competent for your own good, one friend told me. Well I was perfectly happy to admit, now, that I wasn’t. I couldn’t manage weekends alone anymore, I told Dylan’s social worker. Neither Dylan nor I were safe. For Dylan’s well-being and my own safety, I said, if I can’t access some support at weekends then I shall just drive away. I shall leave. I could hardly believe what I heard my mouth say. I wasn’t even aware that I had thought it. I certainly wasn’t sure I could ever do it. But in the silence that followed my announcement, I thought that this must be how breaking point feels.

It took quite a lot for me to admit that I couldn’t keep Dylan safe anymore. Some people have suggested that I might get more support with Dylan if I didn’t appear to cope so well. You appear too competent for your own good, one friend told me. Well I was perfectly happy to admit, now, that I wasn’t. I couldn’t manage weekends alone anymore, I told Dylan’s social worker. Neither Dylan nor I were safe. For Dylan’s well-being and my own safety, I said, if I can’t access some support at weekends then I shall just drive away. I shall leave. I could hardly believe what I heard my mouth say. I wasn’t even aware that I had thought it. I certainly wasn’t sure I could ever do it. But in the silence that followed my announcement, I thought that this must be how breaking point feels. In my

In my  Still, I didn’t cry. I was stoical, this time, not out of heroism or resignation but because the setback wasn’t due to funding problems but rather to ‘concerns about standards of care’. This puts an entirely different complexion on disappointment; parents may be in need of a night off, and young adults in need of a home, but not enough to compromise on safety. So the part of me which was disappointed at the news was outweighed by the part which was relieved. Happily Dylan had not been there; he was still safe with me.

Still, I didn’t cry. I was stoical, this time, not out of heroism or resignation but because the setback wasn’t due to funding problems but rather to ‘concerns about standards of care’. This puts an entirely different complexion on disappointment; parents may be in need of a night off, and young adults in need of a home, but not enough to compromise on safety. So the part of me which was disappointed at the news was outweighed by the part which was relieved. Happily Dylan had not been there; he was still safe with me. These questions matter because it will take months for me to start over; the process of identifying a provider, visiting, arranging assessments, submitting reports, getting the paperwork approved and planning for transition is time-consuming. Perhaps, I suggested to Dylan’s social worker, it would take as long to find an alternative as to wait while any issues were addressed? Especially as an alternative provider would almost certainly mean Dylan moving further away from home (something I had just lost my nerve about in relation to a previous provider). Perhaps you’d consider reinstating that placement? Dylan’s social worker suggested. My magical thinking, it seemed, was being magicked away.

These questions matter because it will take months for me to start over; the process of identifying a provider, visiting, arranging assessments, submitting reports, getting the paperwork approved and planning for transition is time-consuming. Perhaps, I suggested to Dylan’s social worker, it would take as long to find an alternative as to wait while any issues were addressed? Especially as an alternative provider would almost certainly mean Dylan moving further away from home (something I had just lost my nerve about in relation to a previous provider). Perhaps you’d consider reinstating that placement? Dylan’s social worker suggested. My magical thinking, it seemed, was being magicked away. So for now the move is off. I’m on pause. Holding on. I’m not sure whether I will wait or look for somewhere else for Dylan. What is clear though is that I need a break so that I can rest and restore my energy before the long haul. Because whatever happens, it will take a while…

So for now the move is off. I’m on pause. Holding on. I’m not sure whether I will wait or look for somewhere else for Dylan. What is clear though is that I need a break so that I can rest and restore my energy before the long haul. Because whatever happens, it will take a while…