I’ve had cause to reflect on friendship recently, partly triggered by Dylan’s social life and partly by an event in the workplace which left me with some questions. In this post I apply my reflections on Dylan’s relationships to the neurotypical world and suggest ways in which we might re-think ‘friendship’.

Ruby*

Last week I took Dylan to the 21st birthday of a young woman he has known since primary school. Dylan and Ruby have grown into beautiful young adults, I thought to myself as I watched them at the party. Ruby had opted for a disco buffet for her celebration. It was a perfect choice; there is nothing like food and dancing to bring together men and women, old and young, family and friends and the autistic and neurotypical.

Last week I took Dylan to the 21st birthday of a young woman he has known since primary school. Dylan and Ruby have grown into beautiful young adults, I thought to myself as I watched them at the party. Ruby had opted for a disco buffet for her celebration. It was a perfect choice; there is nothing like food and dancing to bring together men and women, old and young, family and friends and the autistic and neurotypical.

Dylan’s dancing style is centrifugal; he and I spun each other around, jumping and hopping in ever-increasing circles. I don’t know what Ruby made of Dylan’s dancing but I figured it might be pretty similar to the way I looked at men at discos when I was her age. She can’t have thought it too awful though as she let her mum dance with Dylan for a while.

As well as dancing Dylan took the opportunity to be wine waiter. He held tightly to a bottle of wine, pouring large glasses and doing ‘chink chink cheers’ with whoever was willing. He also enjoyed the buffet. When my back was turned Dylan removed and ate all the sausages from the sausage rolls, leaving the pastry cases in perfect curls on the plate. I suspect he ate all of the chicken nugget supply. For Dylan, this was the ideal party: there aren’t many places you can steal sausages, play with wine and dance like a dervish.

Dylan and Ruby haven’t always been comfortable sharing their space. Over the years there have been a number of altercations and they have sometimes needed separating. If I got a phone call from school to say Dylan had been involved in an incident I would automatically ask ‘and is Ruby alright?’. They could still annoy each other I’m sure – indeed we had to abort a walk which set off on the wrong foot recently – but, happily, having Dylan at the party was a success.

Stepping stones and splash holes

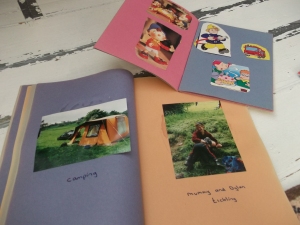

Dylan doesn’t get to go to many parties. When he was young I organised birthday celebrations at autism-friendly venues such as soft play centres. In time, however, I realised these were not enjoyable experiences for Dylan. Birthday parties are stressful; as well as the challenge of the environment and disruption to routine, guests are noisy, unpredictable and annoying. Dylan much preferred to celebrate his birthday with a family meal at a quiet pub.

Dylan doesn’t get to go to many parties. When he was young I organised birthday celebrations at autism-friendly venues such as soft play centres. In time, however, I realised these were not enjoyable experiences for Dylan. Birthday parties are stressful; as well as the challenge of the environment and disruption to routine, guests are noisy, unpredictable and annoying. Dylan much preferred to celebrate his birthday with a family meal at a quiet pub.

Dylan, like many young people with autism, likes to spend time alone. If I arranged for other children to come to the house he would spend the whole visit in a state of anxiety. Other autistic children would go through his DVD collection and toys, interfering with his careful ordering and disrupting his environment. They would want to watch a film which wasn’t on his schedule for the day. Even if they chose the right film, Dylan doesn’t like watching with other people in the room. While generally tolerant of the children he was alongside at school, he didn’t want them in his space at home.

Once I’d realised this I stopped organising such ‘opportunities’. Why impose my ideas of what is appropriate on Dylan? He didn’t want to do play dates. As Dylan entered his adolescent years I discovered that he could tolerate contact with peers for selected activities. A walk in a local valley in the company of a young man Dylan had been at school with was fine, for example; although they didn’t walk together they walked in a similar manner to the same route and destination. Similarly Dylan was quite happy with an occasional picnic trip with Ruby to a bend in the river where they could play separately on the stepping stones (Dylan) and in the splash holes (Ruby).

Ella

It’s hard, as the parent of an autistic child, to know how best to support peer group ‘friendships’. While I didn’t want to put Dylan in situations he found stressful, neither did I wish to write off the potential benefits of peer group contact. As well as respecting Dylan’s preference for spending time alone, however, there were other factors which prevented me from setting up more play dates.

It’s hard, as the parent of an autistic child, to know how best to support peer group ‘friendships’. While I didn’t want to put Dylan in situations he found stressful, neither did I wish to write off the potential benefits of peer group contact. As well as respecting Dylan’s preference for spending time alone, however, there were other factors which prevented me from setting up more play dates.

Organising social events for autistic children is tricky when your child attends a special school. Although you become familiar with the other children on the bus your child travels on, you may never meet their parents. Furthermore, there are few occasions when you get to visit your child’s school at the same time as other families. In this situation it isn’t easy to make connections with the parents of your child’s peer group. It was a happy chance, then, when it turned out that a new friend through my poetry networks had an autistic daughter the same age as Dylan.

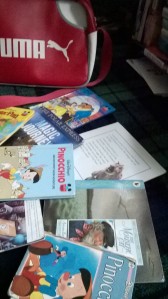

I have written a little about Dylan’s trips out with Ella here, here and here. Although Dylan pays only scant attention to Ella, his relationship with her marks a development in Dylan’s understanding of peer group relationships. He has learned, for example, that he can meet people outside the context of school who have similar interests to him. I’ll never forget Dylan’s astonishment when, visiting Ella at home one day, he discovered that her VHS and DVD collection was almost a complete copy of his own. I also learned, as he pulled all Ella’s films off her shelves and spread them around her bedroom floor (Ella looking on in increasing agitation) that Dylan can be just as annoying to his autistic peers as they are to him.

Christopher*

Dylan’s relationships with Ruby and Ella are fairly typical of his peer group friendships. I don’t think the fact they are with the opposite sex is especially significant although as Dylan grew up in a predominantly female household I suppose he may feel more comfortable with girls. For a while when he was younger, however, Dylan had a quite exceptional friendship with a boy called Christopher.

Dylan’s relationships with Ruby and Ella are fairly typical of his peer group friendships. I don’t think the fact they are with the opposite sex is especially significant although as Dylan grew up in a predominantly female household I suppose he may feel more comfortable with girls. For a while when he was younger, however, Dylan had a quite exceptional friendship with a boy called Christopher.

For a long time I didn’t know about Christopher. One day however, dropping Dylan off at his primary school following an appointment, I was surprised to see him approach another child and give him an excited squeeze. Anxious about the physical contact I made to intervene but Dylan’s class teacher stopped me: ‘It’s alright – that’s Dylan’s little friend ‘ she said. ‘They’re pleased to see each other. ‘Friend? Dylan? I had never seen Dylan pay attention to anyone his own age except for his sister and step-sister.

Dylan treats siblings as honorary adults. At a young age Dylan discovered that people his own size at home could help him to the things he wanted in the same way parents could; they could rewind videos, reach a packet of crisps, fasten shoelaces and play clapping games. ‘Sister’ and ‘Mog’ were therefore acceptable to Dylan. Apart from this, other children (especially if they were smaller) were to be avoided. Until Christopher.

I didn’t have many opportunities to see Dylan and Christopher together. Once however, while shopping at a supermarket the other side of town, Dylan suddenly ran off. When I caught up with Dylan he was at the other side of the checkout counter, holding Christopher’s hand and making greeting noises. I loved that Dylan had spotted his friend and gone to say hello. Later, when we moved to that part of the city, Dylan and Christopher travelled to and from school on the same minibus. I didn’t get to see them together as Dylan was collected before and dropped off after Christopher, but the escort often told me about their special friendship.

Perhaps in time the friendship between Dylan and Christopher would have moved to out of school contact. One day, however, there was an incident on the bus; Christopher and Dylan got upset and in the kerfuffle Dylan was hit by a flailing arm. This had a significant effect on Dylan who became wary, preferring to sit alone on the bus and no longer interacting freely with Christopher. No matter how much I tried to explain that what had happened was an ‘accident’ Dylan could not be reassured. Although it pained me to watch Dylan lose confidence I told myself that the fact he had experienced such feelings meant that, however severe his disability, he was capable of friendship.

Beyond School

Although Dylan has grown into more comfortable relationships with his peer group there has never been another Christopher. When I let myself dream about Dylan’s future, however, I imagine a house with two or three young men, one of whom looks uncannily like him. I suspect I’ve spent the last four years looking for Christopher. ‘Has Dylan developed any special relationships?’ I ask teachers and care workers periodically. The answer is always the same: Not really.

Although Dylan has grown into more comfortable relationships with his peer group there has never been another Christopher. When I let myself dream about Dylan’s future, however, I imagine a house with two or three young men, one of whom looks uncannily like him. I suspect I’ve spent the last four years looking for Christopher. ‘Has Dylan developed any special relationships?’ I ask teachers and care workers periodically. The answer is always the same: Not really.

Key workers and ‘adults who help’ continue to be Dylan’s main reference group. Perhaps that’s not so surprising: Dylan has enough self-awareness to recognise that he needs someone to support him with self care, food preparation and accessing the community. He is probably smart to put his emotional energy into those people he knows have a role in helping him with these things. What does he have to gain from investing time in members of a peer group? They are both the problem (too noisy, unpredictable and annoying) and the competition (also vying for the attention of a ‘helping adult’).

While recognising that Dylan may not prioritise friendships with his peer group, communal living is an experience which I want him to have, especially as Dylan has spent much of his life alone with me. At Ruby’s party I was reminded again of the opportunities which social contact brings; a shared house, I told myself, will help Dylan develop emotional and social skills. From time to time I’ve discussed with other parents the possibility of creating such a house. The problem, of course, is that like-minded parents do not necessarily have well-matched children. In the absence of a peer group chosen by me or identified by Dylan his next move will have to be into an established group. Although I am anxious about this it is, of course, no different to class groups in school. If teachers can manage their classrooms so they are positive environments then surely an adult community can aspire to the same goal?

Back to school

Except the influence which teachers can have on peer group relationships is, I know, limited. Although school years have been described as the happiest days of our lives there is increasing awareness that for many children this is not the case; for some they are the most miserable. In education there is a growing focus on the experience of the child with attempts to access the ‘voice’ of young and disabled children through participatory research methods. Against this background, ‘children’s friendship’ is an increasingly popular focus for enquiry.

Except the influence which teachers can have on peer group relationships is, I know, limited. Although school years have been described as the happiest days of our lives there is increasing awareness that for many children this is not the case; for some they are the most miserable. In education there is a growing focus on the experience of the child with attempts to access the ‘voice’ of young and disabled children through participatory research methods. Against this background, ‘children’s friendship’ is an increasingly popular focus for enquiry.

I attended a seminar given by a colleague on this topic recently. Occasionally one of my undergraduate students opts to focus on friendship for a work placement project and I hoped the seminar would give me ideas for methods and literature I might share. As it was a lunchtime seminar following a busy morning I was concentrating on my sandwich as much as the seminar initially. Soon, however, I noticed that the categorisation of children’s friendship, and particularly its focus on play, were problematic if I made Dylan my reference point. For the next ten minutes I listened with Dylan in mind. This proved a revelation; the conceptualisation of ‘friendship’ simply did not work.

While my colleague was describing research in the area I tried to imagine not just Dylan but other children on the autistic spectrum. It still wasn’t working. So I pushed to what might be considered the ‘mildest’ end of the spectrum; the place where the Aspie girls hang out. These are the girls who may ‘pass’ for years as neurotypical (sometimes a lifetime) because they are bright and articulate with a range of interests. There is increasing interest in these girls; because the diagnostic tool for autism has been primarily derived from, aimed at and applied to boys it is suggested that girls on the Asperger’s end of the spectrum tend to go unidentified. The growing research in the area suggests that for these girls the social experience of school is often miserable; awkward and on the edges, Aspie girls can find it difficult to interpret the environment or fit in. Some of the girls who experience bullying at school, it is suggested, may fall into this group of undiagnosed autistic.

While my colleague was describing research in the area I tried to imagine not just Dylan but other children on the autistic spectrum. It still wasn’t working. So I pushed to what might be considered the ‘mildest’ end of the spectrum; the place where the Aspie girls hang out. These are the girls who may ‘pass’ for years as neurotypical (sometimes a lifetime) because they are bright and articulate with a range of interests. There is increasing interest in these girls; because the diagnostic tool for autism has been primarily derived from, aimed at and applied to boys it is suggested that girls on the Asperger’s end of the spectrum tend to go unidentified. The growing research in the area suggests that for these girls the social experience of school is often miserable; awkward and on the edges, Aspie girls can find it difficult to interpret the environment or fit in. Some of the girls who experience bullying at school, it is suggested, may fall into this group of undiagnosed autistic.

My colleague started to describe one of the girls in her classroom study. She was on the margins. She wasn’t reporting friendships to my colleague using the same language or concepts as the other girls in the study nor was she mentioned by her classmates as a friend; she was, suggested my colleague, socially isolated. The power of educational research is that it is used to support and develop practice; practitioners build ideas from research into their work and promote them in educational environments. The assumption drawn from this particular study was that the isolated girl needed to be helped to develop more appropriate patterns of social interaction, i.e. to form ‘friendships’ with her peers.

The more I thought about the girl in the case study the more I was convinced that it wasn’t she who needed help but the other children in the class. Surely an inclusive environment would be one in which a group is able to support someone who chooses to inhabit the peripheral zone of a classroom? Shouldn’t we be encouraging children to understand that not everyone wants to be sociable and spend their time small talking with peers? Ought we not to be promoting a model of diversity in relation to social interaction in classrooms rather than a monolithic concept of friendship? This girl and Dylan, I realised, were not only not adequately described by this research, they were problematised by it. ‘Friendship’, it seemed, was another of those norms which feel so irrelevant to Dylan’s life and such an obstacle to his inclusion in society. As the vignettes of Dylan’s interactions with some of his peers show, Dylan is capable of forming meaningful relationships; while they might not follow the dominant model of friendship, they are no less valuable for that. As Dylan’s journey into communal living gets underway I will not doubt reflect further on this issue.

*names have been changed.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my colleague for inadvertently providing me with the opportunity to reflect on Dylan’s relationships with others and the conceptualisation of ‘friendship’. My colleague’s research was not concerned with autism but with other issues which I do not address in this post and from which I confess I attempted to divert attention during the latter part of the seminar. My left-field interjections were fielded gracefully 🙂

For information about issues related to ‘Aspie Girls’ there is no better resource than Cynthia Kim’s excellent blog Musings of an Aspie: http://musingsofanaspie.com/about/

Images:

The photos of Dylan and Ella were taken on the banks of the canal at Sheffield and Chesterfield. The pictures of Dylan as an adult were taken at the Under the Stars Disco. The children’s party photos were taken at Dylan’s 6th birthday at a soft play centre. The classroom photo is of a younger me working with a group of primary school children on a writing project. The shadow photo is by (and of) me.

In a previous post I lamented the departure of a member of staff who had coordinated the social enterprise activity at Dylan’s setting. During the recruitment process for a new social enterprise coordinator, the workshop and shop at the residential setting remained closed to members of the public and to residents. This meant that there was a gap in Dylan’s daily schedule which had to be filled with alternative activities. Although staff did their best to keep Dylan purposefully occupied, he was more unsettled during this time and clearly missed his work in the shop.

In a previous post I lamented the departure of a member of staff who had coordinated the social enterprise activity at Dylan’s setting. During the recruitment process for a new social enterprise coordinator, the workshop and shop at the residential setting remained closed to members of the public and to residents. This meant that there was a gap in Dylan’s daily schedule which had to be filled with alternative activities. Although staff did their best to keep Dylan purposefully occupied, he was more unsettled during this time and clearly missed his work in the shop. I am very happy to report that a new social enterprise coordinator is now in post and that Dylan has resumed the ‘anchoring rhythm’ of his daily work in the shop. This seems to be going well. Since the shop re-opened Dylan has been more settled and has seemed generally happier. As well as enjoying the rhythm and structure of working in the shop, it helps that Dylan knows the new coordinator; ‘J’ worked at the National Autistic Society school which Dylan attended so she is a familiar face. Not only does this mean that trust is already established, the continuity in terms of J’s knowledge of Dylan’s interests and skills is fantastic.

I am very happy to report that a new social enterprise coordinator is now in post and that Dylan has resumed the ‘anchoring rhythm’ of his daily work in the shop. This seems to be going well. Since the shop re-opened Dylan has been more settled and has seemed generally happier. As well as enjoying the rhythm and structure of working in the shop, it helps that Dylan knows the new coordinator; ‘J’ worked at the National Autistic Society school which Dylan attended so she is a familiar face. Not only does this mean that trust is already established, the continuity in terms of J’s knowledge of Dylan’s interests and skills is fantastic. The arrival of J has provided an ideal opportunity to review Dylan’s work and to introduce new activities. Since the social enterprise activity resumed Dylan has participated in a range of arts and crafts activities including candle making, paper printing and model making. He has also made ‘book hedgehogs’; these are ingenious creations, made by cutting the pages of a book. I am told that Dylan worked carefully and methodically at the hedgehogs; this is not something I would have expected Dylan to enjoy and reminds me (again) of the importance of keeping an open mind. As well as introducing Dylan to new activities, J is planning to continue the woodwork which Dylan enjoys so much. She has identified some fantastic potential projects for Dylan and a new woodwork bench is due to be delivered. Some new, and more accessible, qualifications are also planned. Exciting times ahead for Dylan and the other residents 🙂

The arrival of J has provided an ideal opportunity to review Dylan’s work and to introduce new activities. Since the social enterprise activity resumed Dylan has participated in a range of arts and crafts activities including candle making, paper printing and model making. He has also made ‘book hedgehogs’; these are ingenious creations, made by cutting the pages of a book. I am told that Dylan worked carefully and methodically at the hedgehogs; this is not something I would have expected Dylan to enjoy and reminds me (again) of the importance of keeping an open mind. As well as introducing Dylan to new activities, J is planning to continue the woodwork which Dylan enjoys so much. She has identified some fantastic potential projects for Dylan and a new woodwork bench is due to be delivered. Some new, and more accessible, qualifications are also planned. Exciting times ahead for Dylan and the other residents 🙂

One of the factors which seemed to be key to Dylan’s engagement with the social enterprise activity was the coordinator (I’ll call him A) with whom Dylan developed an excellent relationship. Dylan seemed to realise that A had a different role to the other staff at the home and this allowed Dylan to adopt a different approach to the relationship. The difference is subtle but significant; because the coordinator is not involved in personal care, an alternative form of trust and closeness was able to develop.

One of the factors which seemed to be key to Dylan’s engagement with the social enterprise activity was the coordinator (I’ll call him A) with whom Dylan developed an excellent relationship. Dylan seemed to realise that A had a different role to the other staff at the home and this allowed Dylan to adopt a different approach to the relationship. The difference is subtle but significant; because the coordinator is not involved in personal care, an alternative form of trust and closeness was able to develop.

What I am struck by is how important these seasonal rhythms are to Dylan. I suppose if you don’t use speech to communicate and have only limited communication, ’embodied’ sense-making through familiar activities is important. I have often thought of Dylan as needing consistency in his life but perhaps it would be more accurate to think of him as needing constancy. The difference between the two is that consistent things do not vary, though they may start and stop, whereas something that is constant does not stop, although it may vary. Dylan seems to be able to manage everyday variations – the absence of a face, a change of detail – providing the anchoring rhythms remain.

What I am struck by is how important these seasonal rhythms are to Dylan. I suppose if you don’t use speech to communicate and have only limited communication, ’embodied’ sense-making through familiar activities is important. I have often thought of Dylan as needing consistency in his life but perhaps it would be more accurate to think of him as needing constancy. The difference between the two is that consistent things do not vary, though they may start and stop, whereas something that is constant does not stop, although it may vary. Dylan seems to be able to manage everyday variations – the absence of a face, a change of detail – providing the anchoring rhythms remain. My presentation at last week’s National Autistic Society conference seemed to go well I’m pleased to say. I will share a summary of it, and some reflections on the conference more generally, very soon. In the meantime I have two pieces of news to share.

My presentation at last week’s National Autistic Society conference seemed to go well I’m pleased to say. I will share a summary of it, and some reflections on the conference more generally, very soon. In the meantime I have two pieces of news to share. Happily I’ve never doubted that the home I eventually chose for Dylan was the best that could be. Even so, it was fantastic to receive independent confirmation of this at the weekend: Dylan’s home, I am delighted to say, has been judged ‘outstanding’ in a CQC Inspection. It’s a wonderful acknowledgment of the time, effort and care the staff and management invest in Dylan and the other young people at the home.

Happily I’ve never doubted that the home I eventually chose for Dylan was the best that could be. Even so, it was fantastic to receive independent confirmation of this at the weekend: Dylan’s home, I am delighted to say, has been judged ‘outstanding’ in a CQC Inspection. It’s a wonderful acknowledgment of the time, effort and care the staff and management invest in Dylan and the other young people at the home. My

My I must have been thinking about this a few days later when I picked up a magnetic letter from Dylan’s bedroom floor. Because I was about to say ‘Oh look Dylan there’s a letter’ or ‘look here’s a W’ when I remembered Elisa’s question ‘Why don’t you ask Dylan what he likes about the paintings?’. Could I be open-ended about the W? Could I ask Dylan what I had found on the floor?

I must have been thinking about this a few days later when I picked up a magnetic letter from Dylan’s bedroom floor. Because I was about to say ‘Oh look Dylan there’s a letter’ or ‘look here’s a W’ when I remembered Elisa’s question ‘Why don’t you ask Dylan what he likes about the paintings?’. Could I be open-ended about the W? Could I ask Dylan what I had found on the floor? Dylan’s magnetic W is the same shape as the version produced by a keyboard: not actually ‘double U’ (as the letter is pronounced in English) but rather ‘Double V’ (as it is pronounced in French). Although this version of W is commonplace today, when I was a child it had curves not angles. In handwriting lessons we were taught to practice forming our Ws by joining Us together and moving our hand briskly and freely across the page, line after line.

Dylan’s magnetic W is the same shape as the version produced by a keyboard: not actually ‘double U’ (as the letter is pronounced in English) but rather ‘Double V’ (as it is pronounced in French). Although this version of W is commonplace today, when I was a child it had curves not angles. In handwriting lessons we were taught to practice forming our Ws by joining Us together and moving our hand briskly and freely across the page, line after line. As well as the mismatch between the visual ‘W’ and the heard shape ‘UU’ I encountered other problems with this letter as a child. I remember sitting on the back step of a friend’s house on a warm day one long school holiday. We had got the writing bug and were sitting in the sun with paper and pens. I don’t know how old we were – perhaps seven or eight, maybe a little older. I remember my friend asked her dad, working in the drive nearby, for a spelling.

As well as the mismatch between the visual ‘W’ and the heard shape ‘UU’ I encountered other problems with this letter as a child. I remember sitting on the back step of a friend’s house on a warm day one long school holiday. We had got the writing bug and were sitting in the sun with paper and pens. I don’t know how old we were – perhaps seven or eight, maybe a little older. I remember my friend asked her dad, working in the drive nearby, for a spelling. Because the names, shapes and sounds of letters aren’t intuitive or easy, attempts have been made by practitioners and publishers to develop teaching resources and methodologies. Whether or not these help probably depends on an individual child’s learning style. A kinaesthetic learner, for example, might respond to the Steiner approach to learning the alphabet through music, movement and drama. This method involves children physically taking on the attributes of each of the letters of the alphabet and embodying learning through the senses. The magnetic letters which I use with Dylan are also aimed at children who learn through their senses as they can be experienced by touch and smell as well as sight.

Because the names, shapes and sounds of letters aren’t intuitive or easy, attempts have been made by practitioners and publishers to develop teaching resources and methodologies. Whether or not these help probably depends on an individual child’s learning style. A kinaesthetic learner, for example, might respond to the Steiner approach to learning the alphabet through music, movement and drama. This method involves children physically taking on the attributes of each of the letters of the alphabet and embodying learning through the senses. The magnetic letters which I use with Dylan are also aimed at children who learn through their senses as they can be experienced by touch and smell as well as sight. As a phonetic method the commercial resource Letterland focuses primarily on sound. Available in a range of formats (jigsaw, books, video etc) it works through the association of each letter with an alliterative character (human or animal). So, for example, C is Clever Cat, J is Jumping Jim and W is Walter Walrus (though when my children were small it was Wicked Water Witch). Many children respond well to the Letterland alphabet – I remember my step daughter liked it and it really did seem to help her developing literacy. It doesn’t suit every child though; my daughter was lukewarm about it and it never held any interest for Dylan. Now, perhaps, I can understand why; Dylan doesn’t hear a Walrus, he sees a see saw.

As a phonetic method the commercial resource Letterland focuses primarily on sound. Available in a range of formats (jigsaw, books, video etc) it works through the association of each letter with an alliterative character (human or animal). So, for example, C is Clever Cat, J is Jumping Jim and W is Walter Walrus (though when my children were small it was Wicked Water Witch). Many children respond well to the Letterland alphabet – I remember my step daughter liked it and it really did seem to help her developing literacy. It doesn’t suit every child though; my daughter was lukewarm about it and it never held any interest for Dylan. Now, perhaps, I can understand why; Dylan doesn’t hear a Walrus, he sees a see saw. Looking again

Looking again

In my

In my  Reading the same book for weeks on end. I used to try and move Dylan on to other texts but later realised that this repetition suits Dylan’s learning style and builds his confidence.

Reading the same book for weeks on end. I used to try and move Dylan on to other texts but later realised that this repetition suits Dylan’s learning style and builds his confidence. Using books as objects, for example to sit on, lick, or wear on the head. Dylan’s sensory and physical relationship with books as artefacts is a valuable part of his developing literacy. Dylan accepts my standards of care for library books, I think, because he has his own copy of favourite books (which I accept will become wet, dirty and torn).

Using books as objects, for example to sit on, lick, or wear on the head. Dylan’s sensory and physical relationship with books as artefacts is a valuable part of his developing literacy. Dylan accepts my standards of care for library books, I think, because he has his own copy of favourite books (which I accept will become wet, dirty and torn). ~ sitting silently next to Dylan with my index finger held out (I discovered that Dylan would take my finger and point to something in the book if he wanted me to name an object or clarify something);

~ sitting silently next to Dylan with my index finger held out (I discovered that Dylan would take my finger and point to something in the book if he wanted me to name an object or clarify something); Numbers and letters are abstract symbols. Some children with an autistic spectrum condition are comfortable with this and demonstrate a facility for mathematics or for learning foreign languages. This is not the case for Dylan, however, for whom numbers and letters as symbols have never appeared meaningful.

Numbers and letters are abstract symbols. Some children with an autistic spectrum condition are comfortable with this and demonstrate a facility for mathematics or for learning foreign languages. This is not the case for Dylan, however, for whom numbers and letters as symbols have never appeared meaningful. Counting things in pictures (the windows in Ulm cathedral is a favourite activity) through chant and point. Whenever Dylan pays attention to something I look for objects we can count, e.g. ‘let’s count the stars’.

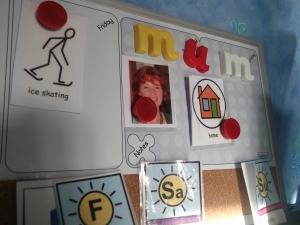

Counting things in pictures (the windows in Ulm cathedral is a favourite activity) through chant and point. Whenever Dylan pays attention to something I look for objects we can count, e.g. ‘let’s count the stars’. Introducing numbers and letters in a naturalistic and comfortable setting. I have introduced m-u-m on Dylan’s visual timetable board because it’s an object which is important to him, that he is comfortable with, and which he interacts with on a daily basis. For other children and adults this might be DVDs, i-pads, the fridge door etc.

Introducing numbers and letters in a naturalistic and comfortable setting. I have introduced m-u-m on Dylan’s visual timetable board because it’s an object which is important to him, that he is comfortable with, and which he interacts with on a daily basis. For other children and adults this might be DVDs, i-pads, the fridge door etc. I did ‘shape work’ with Dylan as part of his home learning programme but am fairly confident that he still doesn’t recognise the words ‘square’, ‘circle’ or ‘triangle’. And who cares? Is it going to make his life any less rich? Does it matter if he doesn’t know the word to describe a shape? As with letters and numbers, Dylan needs a physical object in his hand to recognise the shape of it. I’m sure that he has an intimate understanding of a triangle; if I put one in his hand he would explore it with all his senses (especially if it was a piece of Toblerone). But he wouldn’t recognise the name for it. And he wouldn’t push it into a ‘shape sorter’ with any enthusiasm or success. In fact I used to think Dylan tried to push shapes into the wrong holes deliberately, for a laugh.

I did ‘shape work’ with Dylan as part of his home learning programme but am fairly confident that he still doesn’t recognise the words ‘square’, ‘circle’ or ‘triangle’. And who cares? Is it going to make his life any less rich? Does it matter if he doesn’t know the word to describe a shape? As with letters and numbers, Dylan needs a physical object in his hand to recognise the shape of it. I’m sure that he has an intimate understanding of a triangle; if I put one in his hand he would explore it with all his senses (especially if it was a piece of Toblerone). But he wouldn’t recognise the name for it. And he wouldn’t push it into a ‘shape sorter’ with any enthusiasm or success. In fact I used to think Dylan tried to push shapes into the wrong holes deliberately, for a laugh. Autistic children have good visual-spatial awareness and it is generally assumed that they therefore enjoy doing things based on these skills such as jigsaws. Dylan, however, doesn’t show any enthusiasm or particular ability for jigsaws. I have never been sure whether this is because he finds them difficult or because he finds them boring; although mostly Dylan doesn’t complete jigsaws, sometimes he surprises me by showing that he can. Actually I’m with Dylan on this one; I’ve always found jigsaws fairly pointless. Nonetheless I scheduled them in Dylan’s home learning programme because I thought I should. On reflection it was a waste of time; there were plenty of other things we could have been doing. Some of the activities I did (and still do) with Dylan which develop his visual-spatial skills and which he enjoys include:

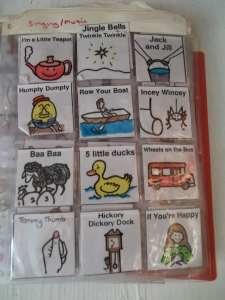

Autistic children have good visual-spatial awareness and it is generally assumed that they therefore enjoy doing things based on these skills such as jigsaws. Dylan, however, doesn’t show any enthusiasm or particular ability for jigsaws. I have never been sure whether this is because he finds them difficult or because he finds them boring; although mostly Dylan doesn’t complete jigsaws, sometimes he surprises me by showing that he can. Actually I’m with Dylan on this one; I’ve always found jigsaws fairly pointless. Nonetheless I scheduled them in Dylan’s home learning programme because I thought I should. On reflection it was a waste of time; there were plenty of other things we could have been doing. Some of the activities I did (and still do) with Dylan which develop his visual-spatial skills and which he enjoys include: Some of Dylan’s most effective exposure to language has been through musical resources; I suspect this is because nursery rhymes and songs use devices such as chorus and repetition which create the pattern and structure which Dylan responds to. Although Dylan has an ambiguous relationship with singing due to his auditory sensitivity (I have written about this

Some of Dylan’s most effective exposure to language has been through musical resources; I suspect this is because nursery rhymes and songs use devices such as chorus and repetition which create the pattern and structure which Dylan responds to. Although Dylan has an ambiguous relationship with singing due to his auditory sensitivity (I have written about this  Making compilations of nursery rhymes and songs for Dylan on key themes to support specific learning (e.g. ‘parts of the body’ or ‘counting’)

Making compilations of nursery rhymes and songs for Dylan on key themes to support specific learning (e.g. ‘parts of the body’ or ‘counting’) What makes the education system fundamentally inaccessible for many children is the role of language in the delivery of the curriculum. A key challenge for parents and educators is therefore how to make learning accessible for children who do not speak or use an alternative communication system. Dylan is currently developing some echolalic speech but for the majority of his life, and throughout his schooling, has been classed as ‘non-verbal’. It is perhaps not surprising that so many of the suggestions in this post focus on language development; it is in its potential for adaptations to language, I suspect, that a home learning programme may be of particular value.

What makes the education system fundamentally inaccessible for many children is the role of language in the delivery of the curriculum. A key challenge for parents and educators is therefore how to make learning accessible for children who do not speak or use an alternative communication system. Dylan is currently developing some echolalic speech but for the majority of his life, and throughout his schooling, has been classed as ‘non-verbal’. It is perhaps not surprising that so many of the suggestions in this post focus on language development; it is in its potential for adaptations to language, I suspect, that a home learning programme may be of particular value. In a

In a  caregivers and educators we orchestrate them. In my

caregivers and educators we orchestrate them. In my  philosophy

philosophy The four categories of intervention activity are underpinned by philosophical ideas because they align with academic disciplines and thus with theory as well as practice. Sensory interventions, for example, draw on ideas from Occupational Therapy while behaviourism is based on theory from Psychology and dietary and medical interventions align with disciplinary fields such as biochemistry and neuroscience.

The four categories of intervention activity are underpinned by philosophical ideas because they align with academic disciplines and thus with theory as well as practice. Sensory interventions, for example, draw on ideas from Occupational Therapy while behaviourism is based on theory from Psychology and dietary and medical interventions align with disciplinary fields such as biochemistry and neuroscience.

It was by instinct, however, that I developed what I called ‘video teaching’. I’m not sure whether it was original (probably not) but I came up with it one night, alone and restlessly awake, praying for a good idea by morning. Dylan would have been around four years old at this point and his love of video was already clear. The only time Dylan was still was watching Pingu, Postman Pat or Thomas the Tank Engine. He would sit on a cushion in front of the television, periodically flapping his hands or making an excited ‘shushing’ noise with a little tremble of his head. However often Dylan watched, he was always engaged; this, I thought to myself, was the focus I needed.

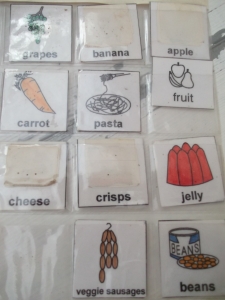

It was by instinct, however, that I developed what I called ‘video teaching’. I’m not sure whether it was original (probably not) but I came up with it one night, alone and restlessly awake, praying for a good idea by morning. Dylan would have been around four years old at this point and his love of video was already clear. The only time Dylan was still was watching Pingu, Postman Pat or Thomas the Tank Engine. He would sit on a cushion in front of the television, periodically flapping his hands or making an excited ‘shushing’ noise with a little tremble of his head. However often Dylan watched, he was always engaged; this, I thought to myself, was the focus I needed. It was the late 1990s, before the introduction of digital technology. Fortunately I had access to recording equipment at work so one holiday I borrowed a large, heavy camera. With the help of my six year old step-daughter, husband and mum I made ‘home teaching videos’ for Dylan. These involved flash cards and objects in real life contexts. In one scene, for example, my mum held a fork and flashcard in her hand while saying: Fork Dylan. It’s a fork. F-O-R-K. Fork. Then she mimed eating with the fork. Having the flashcard and the object, and hearing the word pronounced repeatedly, was an attempt to engage Dylan as a visual as well as an aural learner. It also allowed for the possibility that although Dylan didn’t speak he might be able to read (this hasn’t turned out to be the case).

It was the late 1990s, before the introduction of digital technology. Fortunately I had access to recording equipment at work so one holiday I borrowed a large, heavy camera. With the help of my six year old step-daughter, husband and mum I made ‘home teaching videos’ for Dylan. These involved flash cards and objects in real life contexts. In one scene, for example, my mum held a fork and flashcard in her hand while saying: Fork Dylan. It’s a fork. F-O-R-K. Fork. Then she mimed eating with the fork. Having the flashcard and the object, and hearing the word pronounced repeatedly, was an attempt to engage Dylan as a visual as well as an aural learner. It also allowed for the possibility that although Dylan didn’t speak he might be able to read (this hasn’t turned out to be the case). As well as instinct I drew on approaches to working with autistic children which were current at the time. I used ‘start-finish’ baskets as advocated by TEACCH programmes, for example. Although I had rejected behaviourism for Dylan I borrowed the approach to pace and rhythm adopted by the

As well as instinct I drew on approaches to working with autistic children which were current at the time. I used ‘start-finish’ baskets as advocated by TEACCH programmes, for example. Although I had rejected behaviourism for Dylan I borrowed the approach to pace and rhythm adopted by the  At the time, my focus was very much on finding alternative ways of working with Dylan. I didn’t believe the child development manuals had anything to offer us and the school curriculum seemed irrelevant. As far as I was concerned, what I had to do with Dylan was utterly different to the approach I took with his neurotypical sister. When I worked with Dylan I felt as if I was somewhere otherly and without a map; I was, I thought, a cartographer.

At the time, my focus was very much on finding alternative ways of working with Dylan. I didn’t believe the child development manuals had anything to offer us and the school curriculum seemed irrelevant. As far as I was concerned, what I had to do with Dylan was utterly different to the approach I took with his neurotypical sister. When I worked with Dylan I felt as if I was somewhere otherly and without a map; I was, I thought, a cartographer. I read the list of activities (which relate to any home learning rather than specialist provision) several times. What struck me is that it was a perfect description of my current life with Dylan; in the course of a week, we do all of these things. There is a sense in which time stands still, or moves slowly, when living with autism; at 20, Dylan is rehearsing many of the same skills he was at five. I fetched my crate of home education resources from the cellar and looked through them; the early intervention activities I did with Dylan fitted the Aboucher and Desforges’ framework well.

I read the list of activities (which relate to any home learning rather than specialist provision) several times. What struck me is that it was a perfect description of my current life with Dylan; in the course of a week, we do all of these things. There is a sense in which time stands still, or moves slowly, when living with autism; at 20, Dylan is rehearsing many of the same skills he was at five. I fetched my crate of home education resources from the cellar and looked through them; the early intervention activities I did with Dylan fitted the Aboucher and Desforges’ framework well. I probably didn’t do anything different with Dylan 16 years ago, in terms of focus, than an early years educator would do with any child. What was different, however, was the way in which Dylan engaged with the books, numbers, letters, shapes, nursery rhymes and singing. In a

I probably didn’t do anything different with Dylan 16 years ago, in terms of focus, than an early years educator would do with any child. What was different, however, was the way in which Dylan engaged with the books, numbers, letters, shapes, nursery rhymes and singing. In a  If the activities I do with Dylan haven’t changed in the last 16 years happily I have; I can still enjoy that wonderful thing, hindsight, while standing still. And if I had my time again I would do some things differently; I would, for example, focus more on interventions based on OT (an

If the activities I do with Dylan haven’t changed in the last 16 years happily I have; I can still enjoy that wonderful thing, hindsight, while standing still. And if I had my time again I would do some things differently; I would, for example, focus more on interventions based on OT (an