In a previous post I reflected on the pressure which parents can feel under to take action in the aftermath of an autism diagnosis; early intervention, we are told, can play a critical role in future outcomes. Following Dylan’s diagnosis 18 years ago I trialled a long list of therapies. These interventions, I suggested in my earlier post, could be categorised as sensory; dietary and medical; behavioural; and educational. This is the last in a series of posts reviewing these approaches in turn.

In a previous post I reflected on the pressure which parents can feel under to take action in the aftermath of an autism diagnosis; early intervention, we are told, can play a critical role in future outcomes. Following Dylan’s diagnosis 18 years ago I trialled a long list of therapies. These interventions, I suggested in my earlier post, could be categorised as sensory; dietary and medical; behavioural; and educational. This is the last in a series of posts reviewing these approaches in turn.

Orchestrating interventions

No single approach is sufficient in itself and I doubt there are any parents or professionals who focus exclusively on one of the four categories of intervention I identify above. The question, for most parents, is the balance between the categories and the way as  caregivers and educators we orchestrate them. In my introductory post to this series I identified some of the factors which impact on our choice of therapy: the child; parental values; the available resources; and the ‘dominant discourse’ abut autism at the time. As well as influencing our adoption of individual therapies, these factors affect the way we combine them.

caregivers and educators we orchestrate them. In my introductory post to this series I identified some of the factors which impact on our choice of therapy: the child; parental values; the available resources; and the ‘dominant discourse’ abut autism at the time. As well as influencing our adoption of individual therapies, these factors affect the way we combine them.

One hypothetical parent of a pre-school child, for example, may opt for a gluten and casein-free diet with sensory-based interventions such as weighted blankets, massage, music therapy and gross motor activities. Such a parent may adopt a non-directive approach, preferring not to use behaviourist interventions or to offer their child formal education. Another hypothetical parent, meanwhile, may focus on the re-shaping of behaviour through a programme of rewards and reinforcers based on behaviourist  philosophy. Such an intervention would include educational input as behaviourist approaches are used to facilitate cognitive as well as social learning; the framework for the educational content, however, would be social.

philosophy. Such an intervention would include educational input as behaviourist approaches are used to facilitate cognitive as well as social learning; the framework for the educational content, however, would be social.

The two hypothetical parents in the above examples are a bit stereotypical. While it is often the case that a family opting for a behaviourist programme will place less emphasis on sensory approaches it is possible to mix and match eclectically from the four categories. To a large extent this was the approach I took with Dylan. However, as my earlier posts in this series indicate, the different interventions map onto distinct sets of ideas so choosing a particular intervention also involves adopting a particular philosophy.

Why education?

The four categories of intervention activity are underpinned by philosophical ideas because they align with academic disciplines and thus with theory as well as practice. Sensory interventions, for example, draw on ideas from Occupational Therapy while behaviourism is based on theory from Psychology and dietary and medical interventions align with disciplinary fields such as biochemistry and neuroscience.

The four categories of intervention activity are underpinned by philosophical ideas because they align with academic disciplines and thus with theory as well as practice. Sensory interventions, for example, draw on ideas from Occupational Therapy while behaviourism is based on theory from Psychology and dietary and medical interventions align with disciplinary fields such as biochemistry and neuroscience.

As an academic discipline as well as a field of practice, education offers activities underpinned by theories about learning and child development. Given my work as an educator, this was a comfortable place for me; the language and philosophy felt familiar even in the transformed landscape of an autism diagnosis. After half-hearted trials with other interventions, and an abandoned attempt at a behaviourist programme, education was therefore what I chose.

Parent and educator

Initially I proceeded by instinct, aware that my assumptions about teaching and learning could be a burden rather than an asset when working with Dylan: in order to become a better educator I had to do what I asked of my students and unlearn some of my beliefs about education. Although I tried to bracket my professional experience I did draw on some practices from the workplace such as systematic planning and recording. I probably didn’t realise at the time how useful this was but looking back I can see that the framework it provided was helpful for me as well as for Dylan.

It isn’t easy for a parent to take on the role of educator. The most significant challenge I faced was without doubt my ability to cope emotionally. The inevitable frustrations and setbacks can be hard when you are emotionally involved with the child. You cannot walk away from the situation at the end of a difficult day. It can be harder to evaluate learning objectively; sometimes I wore rose-coloured spectacles and sometimes dark lenses. Furthermore, the potential for confusion of role between mother and son, teacher and child, presents particular challenges in the context of autism.

It is perhaps not surprising that many parents prefer to employ people to work with their children – indeed, this is recommended by behaviourist programmes. This wasn’t an option for me however; finances didn’t stretch to employing assistants for Dylan. Besides, I argued to myself, I had the necessary skills as well as instinct.

Intervention by instinct

It was by instinct, however, that I developed what I called ‘video teaching’. I’m not sure whether it was original (probably not) but I came up with it one night, alone and restlessly awake, praying for a good idea by morning. Dylan would have been around four years old at this point and his love of video was already clear. The only time Dylan was still was watching Pingu, Postman Pat or Thomas the Tank Engine. He would sit on a cushion in front of the television, periodically flapping his hands or making an excited ‘shushing’ noise with a little tremble of his head. However often Dylan watched, he was always engaged; this, I thought to myself, was the focus I needed.

It was by instinct, however, that I developed what I called ‘video teaching’. I’m not sure whether it was original (probably not) but I came up with it one night, alone and restlessly awake, praying for a good idea by morning. Dylan would have been around four years old at this point and his love of video was already clear. The only time Dylan was still was watching Pingu, Postman Pat or Thomas the Tank Engine. He would sit on a cushion in front of the television, periodically flapping his hands or making an excited ‘shushing’ noise with a little tremble of his head. However often Dylan watched, he was always engaged; this, I thought to myself, was the focus I needed.

It was the late 1990s, before the introduction of digital technology. Fortunately I had access to recording equipment at work so one holiday I borrowed a large, heavy camera. With the help of my six year old step-daughter, husband and mum I made ‘home teaching videos’ for Dylan. These involved flash cards and objects in real life contexts. In one scene, for example, my mum held a fork and flashcard in her hand while saying: Fork Dylan. It’s a fork. F-O-R-K. Fork. Then she mimed eating with the fork. Having the flashcard and the object, and hearing the word pronounced repeatedly, was an attempt to engage Dylan as a visual as well as an aural learner. It also allowed for the possibility that although Dylan didn’t speak he might be able to read (this hasn’t turned out to be the case).

It was the late 1990s, before the introduction of digital technology. Fortunately I had access to recording equipment at work so one holiday I borrowed a large, heavy camera. With the help of my six year old step-daughter, husband and mum I made ‘home teaching videos’ for Dylan. These involved flash cards and objects in real life contexts. In one scene, for example, my mum held a fork and flashcard in her hand while saying: Fork Dylan. It’s a fork. F-O-R-K. Fork. Then she mimed eating with the fork. Having the flashcard and the object, and hearing the word pronounced repeatedly, was an attempt to engage Dylan as a visual as well as an aural learner. It also allowed for the possibility that although Dylan didn’t speak he might be able to read (this hasn’t turned out to be the case).

Dylan loved the videos; he would happily watch them through over and over, seeming to enjoy seeing familiar people and objects on the screen. I’m not sure how much Dylan learned from the videos – he almost certainly didn’t engage with the flashcards and at 20 still struggles to recognise some of the vocabulary – but I think they were worthwhile nonetheless. Video teaching taught me that a home learning programme is a good way of involving the wider family (my step-daughter had great fun making the videos). It also demonstrated to me that Dylan could focus if I developed materials which were engaging and in a format with which he was comfortable.

The home learning environment

As well as instinct I drew on approaches to working with autistic children which were current at the time. I used ‘start-finish’ baskets as advocated by TEACCH programmes, for example. Although I had rejected behaviourism for Dylan I borrowed the approach to pace and rhythm adopted by the PEACH programme; working in short bursts seemed appropriate for Dylan and chunking up the sessions provided me with a robust structure when planning. I also borrowed some instructional techniques and based Dylan’s work space on a mash-up of TEACCH and PEACH; eclectic, but so what if it worked?

As well as instinct I drew on approaches to working with autistic children which were current at the time. I used ‘start-finish’ baskets as advocated by TEACCH programmes, for example. Although I had rejected behaviourism for Dylan I borrowed the approach to pace and rhythm adopted by the PEACH programme; working in short bursts seemed appropriate for Dylan and chunking up the sessions provided me with a robust structure when planning. I also borrowed some instructional techniques and based Dylan’s work space on a mash-up of TEACCH and PEACH; eclectic, but so what if it worked?

At the time, my focus was very much on finding alternative ways of working with Dylan. I didn’t believe the child development manuals had anything to offer us and the school curriculum seemed irrelevant. As far as I was concerned, what I had to do with Dylan was utterly different to the approach I took with his neurotypical sister. When I worked with Dylan I felt as if I was somewhere otherly and without a map; I was, I thought, a cartographer.

At the time, my focus was very much on finding alternative ways of working with Dylan. I didn’t believe the child development manuals had anything to offer us and the school curriculum seemed irrelevant. As far as I was concerned, what I had to do with Dylan was utterly different to the approach I took with his neurotypical sister. When I worked with Dylan I felt as if I was somewhere otherly and without a map; I was, I thought, a cartographer.

Marking a student’s essay recently, however, I read something which gave me pause for thought. Aboucher and Desforges, my student informed me, describe a Home Learning Environment (HLE) as one that is made up of:

reading, library visits, playing with numbers and letters, playing with shapes, teaching nursery rhymes and singing.

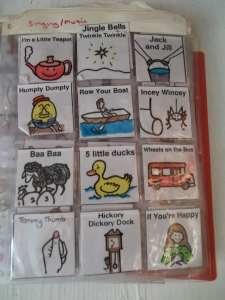

I read the list of activities (which relate to any home learning rather than specialist provision) several times. What struck me is that it was a perfect description of my current life with Dylan; in the course of a week, we do all of these things. There is a sense in which time stands still, or moves slowly, when living with autism; at 20, Dylan is rehearsing many of the same skills he was at five. I fetched my crate of home education resources from the cellar and looked through them; the early intervention activities I did with Dylan fitted the Aboucher and Desforges’ framework well.

I read the list of activities (which relate to any home learning rather than specialist provision) several times. What struck me is that it was a perfect description of my current life with Dylan; in the course of a week, we do all of these things. There is a sense in which time stands still, or moves slowly, when living with autism; at 20, Dylan is rehearsing many of the same skills he was at five. I fetched my crate of home education resources from the cellar and looked through them; the early intervention activities I did with Dylan fitted the Aboucher and Desforges’ framework well.

I probably didn’t do anything different with Dylan 16 years ago, in terms of focus, than an early years educator would do with any child. What was different, however, was the way in which Dylan engaged with the books, numbers, letters, shapes, nursery rhymes and singing. In a linked post I provide illustrations which, as well as demonstrating the role of a HLE in supporting an autistic child, offer practical ideas for parents within the categories identified by Aboucher and Desforges.

I probably didn’t do anything different with Dylan 16 years ago, in terms of focus, than an early years educator would do with any child. What was different, however, was the way in which Dylan engaged with the books, numbers, letters, shapes, nursery rhymes and singing. In a linked post I provide illustrations which, as well as demonstrating the role of a HLE in supporting an autistic child, offer practical ideas for parents within the categories identified by Aboucher and Desforges.

Hindsight standing still

If the activities I do with Dylan haven’t changed in the last 16 years happily I have; I can still enjoy that wonderful thing, hindsight, while standing still. And if I had my time again I would do some things differently; I would, for example, focus more on interventions based on OT (an earlier post describes activities I think particularly helpful). While I did fine motor work with Dylan (cutting, threading, shape sorting) I probably didn’t place enough emphasis on physical activity. There was only limited understanding, at the time, of sensory profiling; of the various developments in the last couple of decades I would say that our knowledge of sensory issues has made the most significant difference to the support we can offer our children.

If the activities I do with Dylan haven’t changed in the last 16 years happily I have; I can still enjoy that wonderful thing, hindsight, while standing still. And if I had my time again I would do some things differently; I would, for example, focus more on interventions based on OT (an earlier post describes activities I think particularly helpful). While I did fine motor work with Dylan (cutting, threading, shape sorting) I probably didn’t place enough emphasis on physical activity. There was only limited understanding, at the time, of sensory profiling; of the various developments in the last couple of decades I would say that our knowledge of sensory issues has made the most significant difference to the support we can offer our children.

In the introduction to this post I restated the four factors I believe drive decisions about intervention: the child, the parent, the available resources and the dominant discourse. A better understanding of Dylan’s needs when he was diagnosed might have led me to adopt a sensory-based approach to early intervention. While my choice of intervention may not have been sufficiently focused on the child, however, neither was it driven by prevailing discourses at the time; I rejected the use of behaviourist and dietary/medical interventions as a potential ‘cure’ for autism. While I’m not uncomfortable with my decision to focus on educational intervention following diagnosis, Dylan didn’t benefit from my HLE in the way I had hoped.

In the introduction to this post I restated the four factors I believe drive decisions about intervention: the child, the parent, the available resources and the dominant discourse. A better understanding of Dylan’s needs when he was diagnosed might have led me to adopt a sensory-based approach to early intervention. While my choice of intervention may not have been sufficiently focused on the child, however, neither was it driven by prevailing discourses at the time; I rejected the use of behaviourist and dietary/medical interventions as a potential ‘cure’ for autism. While I’m not uncomfortable with my decision to focus on educational intervention following diagnosis, Dylan didn’t benefit from my HLE in the way I had hoped.

On reflection, the decision to focus on educational interventions was based on my needs not Dylan’s. While working intensively with Dylan developed my practice, Dylan didn’t acquire the skills I had intended. Early intervention, it turned out, would bring about changes in me, the parent, rather than in the child. In the years since, I have wondered if the transformation of parental attitudes and beliefs is the main value of such initiatives. This surely is invaluable? A child’s parents are his or her greatest resource and time invested in the relationship is, perhaps, the mother of all interventions.

Reference:

Desforges P. and Aboucher, A. (2003) The Impact of Parental Involvement, Parental Support and Family Education on Pupil Achievement and Adjustment: A Literature Review. Queen’s Printer: Exeter

Images:

The images in the post are examples of my early planning and recording, Dylan’s ‘work’ from the time and pages from his ‘red book’, a resource I developed to support the home education programme.

Thank you for supporting our blog in 2014

Best wishes for 2015

Liz and Dylan

🙂