Or, as happens to be the case, The Unshaking Man. Happily, Dylan hasn’t had a seizure since June 2021 when he received a diagnosis of epilepsy following three generalised tonic clonic seizures within six months. At least, as far as we know he hasn’t.

Straws & Water

‘Could you remind staff to offer Dylan extra fluid’, I emailed his care home during this week’s heatwave. One connection that was made, during Dylan’s previous seizures, was with hot weather. Another observation that was made, at the time, was with coronavirus. Dylan, like many young people with autism, found lockdown difficult. There is evidence that epileptic seizures can be brought on by anxiety, something worth considering in relation to a young man whose lack of capacity and speech often leave him with extreme anxiety. This was almost certainly made worse by the pandemic.

‘Could you remind staff to offer Dylan extra fluid’, I emailed his care home during this week’s heatwave. One connection that was made, during Dylan’s previous seizures, was with hot weather. Another observation that was made, at the time, was with coronavirus. Dylan, like many young people with autism, found lockdown difficult. There is evidence that epileptic seizures can be brought on by anxiety, something worth considering in relation to a young man whose lack of capacity and speech often leave him with extreme anxiety. This was almost certainly made worse by the pandemic.

At least, that seems a reasonable assumption. It’s not easy to make claims about the medical and social impact of the coronavirus pandemic. While I don’t go looking for hypotheses or urban myths, I trip over a fair few in my real and parasocial lives (although as I’ve recently closed my social media accounts, I should encounter fewer in future). I tend to ignore these and would certainly not want to be responsible for spreading disinformation.

However, something that I’ve been struck by (and hope someone somewhere is investigating) is sudden onset of epilepsy in adults following covid infection. I’ve spoken to several people (in clinical and other settings, as I’ve been supporting Dylan or accessing services myself) who’ve mentioned an adult family member who had an epileptic fit during the pandemic. These were described as one-off incidents that hadn’t developed into regular seizures, as seems to have been the case with Dylan. Maybe I’m clutching at straws, but the possibility that Dylan’s fits were triggered by a covid infection reassures me. I suppose because it would reduce the likelihood of it happening again.

Still, best keep that water bottle topped up.

Scales & Granules

‘How has Dylan put on a stone in weight?’ I asked the care home manager. I already had a suspicion that he wasn’t getting enough exercise (which I’ve written about here). Now the possibility that Dylan’s sweet tooth had outwitted the support workers presented itself. We set up a Food Diary to identify any unhealthy habits. When nothing emerged, it occurred to me that Dylan’s weight gain might be linked to the daily 800 mg of Epilim Chronosphere granules (a form of sodium valproate) he has taken since his epilepsy diagnosis. A call to the GP confirmed this was likely: ‘lifestyle changes would need to be made’, the doctor advised, ‘to offset the long-term impact of the medication’.

‘How has Dylan put on a stone in weight?’ I asked the care home manager. I already had a suspicion that he wasn’t getting enough exercise (which I’ve written about here). Now the possibility that Dylan’s sweet tooth had outwitted the support workers presented itself. We set up a Food Diary to identify any unhealthy habits. When nothing emerged, it occurred to me that Dylan’s weight gain might be linked to the daily 800 mg of Epilim Chronosphere granules (a form of sodium valproate) he has taken since his epilepsy diagnosis. A call to the GP confirmed this was likely: ‘lifestyle changes would need to be made’, the doctor advised, ‘to offset the long-term impact of the medication’.

‘Lifestyle changes’ in relation to food for someone who is autistic and who lacks capacity (and for whom food is a key interest and pleasure) are not easy to make. In fact, they are rather difficult for Dylan and likely to make him unhappy. Clearly, however, it is in Dylan’s best interest to maintain a healthy weight. If it is the Epilim granules that are raising the reading on the scales, then we must support Dylan to make those lifestyle changes. ‘Just one trip a week to Costa for millionaire’s shortbread, Dylan’.

Happily, once we’d introduced a few changes Dylan quickly shed the excess weight and he is back to his lithe and lovely self. The potential impact of his medication on general health and wellbeing, over the longer term, does raise some questions for me, however.

- Is the Epilim preventing Dylan from having epileptic seizures?

- What if the seizures Dylan had were due to covid or lockdown anxiety?

If the absence of seizures is a result of effective prescribing, an associated weight gain seems an acceptable price to pay. But neither weight gain nor requiring Dylan to make distressing lifestyle changes are justifiable for unnecessary medication. The only way to test for this (controlled reduction of the medication) carries risks. It’s harder to argue the case to trial this with someone else, than for yourself.

Best keep giving the granules, then.

Epilepsy & Empathy

In June 2021, when Dylan had his third and most dramatic seizure, I happened to be reading The Shaking Woman by Siri Hustvedt. The book had been recommended to me by a colleague who suffers from migraines. He had found Hustvedt’s story helpful in managing what had become for him an almost debilitating condition. Reading it might help me to understand my daughter’s severe attacks and to feel more able to support her, he said.

In June 2021, when Dylan had his third and most dramatic seizure, I happened to be reading The Shaking Woman by Siri Hustvedt. The book had been recommended to me by a colleague who suffers from migraines. He had found Hustvedt’s story helpful in managing what had become for him an almost debilitating condition. Reading it might help me to understand my daughter’s severe attacks and to feel more able to support her, he said.

Hustvedt’s story begins in 2006 at a memorial service for her father at the American University where he had been professor of Norwegian until his death in 2004. Siri (an experienced public speaker) is about to deliver an address:

Confident and armed with index cards, I looked out at the fifty or so friends and colleagues of my father’s who had gathered around the memorial Norway spruce, launched into my first sentence, and began to shudder violently from the neck down. My arms flapped. My knees knocked. I shook as if I were having a seizure. Weirdly, my voice wasn’t affected. It didn’t change at all. Astounded by what was happening to me and terrified that I would fall over, I managed to keep my balance and continue, despite the fact that the cards in my hands were flying back and forth in front of me. When the speech ended, the shaking stopped. I looked down at my legs. They had turned a deep red with a bluish cast. (p.3)

Epilepsy is ‘the most famous of all the shaking illnesses’, but Hustvedt’s convulsive illness differed in that it did not interrupt her awareness or speech. The medical center which treated her following the incident diagnosed vascular migraine syndrome. Hustvedt (who had suffered from migraines since childhood) reflected:

Whatever had happened to me, whatever name could be assigned to my affliction, my strange seizure must have had an emotional component that was somehow connected to my father. (p.7).

To make sense of the condition, Hustvedt (who experienced further episodes) embarked on a journey through neurology, psychiatry, and psychoanalysis. What strikes me about Hustvedt’s carefully researched account is the close link it makes between migraine and epilepsy. I began the book in a quest to understand my daughter’s migraines but kept stumbling into my shaking son. Also striking is the possibility that the emotions (specifically empathy) play in role in both conditions.

The nervous overload which triggers migraine attacks and convulsions, it is suggested, could arise from ‘excessive empathy’. Through this lens, a migraine attack or epileptic seizure may be the result of a sufferer identifying too closely with the experience of others. We might describe this as being ‘over-sensitive’ to the feelings of others or (more positively) as emotional intuition. Could it be the case that an awareness of the emotional state of others (in a family, social or professional environment) may lead some people to experience a migraine or seizure? Thinking about the stories in Hustvedt’s book, and my observations of my children and colleagues, I wouldn’t rule out the possibility.

Autistic people, we are sometimes told, are not capable of empathy, but this is an increasingly discredited narrative and one which I have countered in several posts. Now, when I think back to the pandemic years, it strikes me as quite plausible that Dylan (without language or the capacity to comprehend events) relied on his emotional antennae to process what was happening at the time. Although we tried to conceal our anxiety and uncertainty from him, more than likely Dylan will have picked this up from those around him.

Best try to be a zen mum, then 🙂

Notes:

Siri Hustvedt, The Shaking Woman or A History of my Nerves (Hodder & Stoughton, 2011)

Dylan and I were on the canal tow path near Bingley on Thursday 8th September when my phone pinged. I had taken Dylan on an overnight visit to see the 3- and 5-Rise locks on the Leeds-Liverpool Canal. Dylan loves water and is fascinated by engineering so I figured the locks might capture his interest (and mine). We had walked to Saltaire that morning and were heading back for a late lunch at the 5-Rise café when my phone interrupted us.

Dylan and I were on the canal tow path near Bingley on Thursday 8th September when my phone pinged. I had taken Dylan on an overnight visit to see the 3- and 5-Rise locks on the Leeds-Liverpool Canal. Dylan loves water and is fascinated by engineering so I figured the locks might capture his interest (and mine). We had walked to Saltaire that morning and were heading back for a late lunch at the 5-Rise café when my phone interrupted us.  It didn’t take long, following Dylan’s autism diagnosis, for me to realise that visual images – photographs, symbols, videos – would play a central role in his life. One of my earliest memories of that time is of walking around the village where we lived, photographing places we visited to add to the communication book I was making. It was 1996 and Dylan had just turned two. Digital photography and mobile phones had not yet landed. I shot rolls and rolls of film in those early years and (with an industrial camera which made my shoulder ache) produced numerous home videos – not to record, celebrate or share our lives, as is the case today, but as teaching resources for Dylan’s home education programme and communication aids to support our family life.

It didn’t take long, following Dylan’s autism diagnosis, for me to realise that visual images – photographs, symbols, videos – would play a central role in his life. One of my earliest memories of that time is of walking around the village where we lived, photographing places we visited to add to the communication book I was making. It was 1996 and Dylan had just turned two. Digital photography and mobile phones had not yet landed. I shot rolls and rolls of film in those early years and (with an industrial camera which made my shoulder ache) produced numerous home videos – not to record, celebrate or share our lives, as is the case today, but as teaching resources for Dylan’s home education programme and communication aids to support our family life. Such visual supports are helpful for any child who receives an autism diagnosis but for Dylan, who has remained non-verbal, they are essential. The visual world is Dylan’s language, his ‘mother tongue’. At 28 years old, Dylan has a vast visual vocabulary, supported by thousands of photographs taken over the course of his life. Dylan processes, organises and records visual information at astonishing speed. He can scan an environment and log it visually within minutes. When Dylan is given his visual programme for the day, his eyes flick quickly through the images, absorbing the information. If he encounters an unfamiliar symbol or photograph, he scrutinises it intently, looking for clues, before asking for more information or (sometimes) becoming anxious about what he doesn’t understand.

Such visual supports are helpful for any child who receives an autism diagnosis but for Dylan, who has remained non-verbal, they are essential. The visual world is Dylan’s language, his ‘mother tongue’. At 28 years old, Dylan has a vast visual vocabulary, supported by thousands of photographs taken over the course of his life. Dylan processes, organises and records visual information at astonishing speed. He can scan an environment and log it visually within minutes. When Dylan is given his visual programme for the day, his eyes flick quickly through the images, absorbing the information. If he encounters an unfamiliar symbol or photograph, he scrutinises it intently, looking for clues, before asking for more information or (sometimes) becoming anxious about what he doesn’t understand. The photos developed from hundreds of rolls of analogue film have, of course, been superseded by digital images stored on various devices: computers, lap tops, iPads, iPhone and USB sticks. These technological developments may not have been made with disabled people in mind but they have helped to meet Dylan’s needs as a non-verbal autistic man with an intellectual disability. In particular, phone-based photography has given Dylan access to a portable archive which he uses for a range of purposes. Dylan browses the photos on my phone to communicate, for personal pleasure and for reassurance. Sometimes, multiple functions are served at once; while having a drink in a pub, for example, Dylan will scroll through the images on my phone while I read, the pleasure and reassurance he finds in this activity punctuated by conversations about selected images.

The photos developed from hundreds of rolls of analogue film have, of course, been superseded by digital images stored on various devices: computers, lap tops, iPads, iPhone and USB sticks. These technological developments may not have been made with disabled people in mind but they have helped to meet Dylan’s needs as a non-verbal autistic man with an intellectual disability. In particular, phone-based photography has given Dylan access to a portable archive which he uses for a range of purposes. Dylan browses the photos on my phone to communicate, for personal pleasure and for reassurance. Sometimes, multiple functions are served at once; while having a drink in a pub, for example, Dylan will scroll through the images on my phone while I read, the pleasure and reassurance he finds in this activity punctuated by conversations about selected images. Not only have these advances in photography helped me to create a visual archive for Dylan, they have enabled the production of instant images. Being able to record Dylan in the landscape and share this with him immediately has strengthened his sense of place and helped him to develop a sense of identity and belonging. This has been further helped by the ‘selfie’ option, which has allowed Dylan to locate himself in the landscape with others and has enabled him to take photographs himself, with minimum support. How marvellous that there have been all these developments in Dylan’s lifetime, I used to think to myself. Used to? Yes, because this has all changed. Suddenly (I suspect) and recently (I think). Although I can’t be sure – maybe I only noticed suddenly and recently and it had been brewing a while? I am having to re-think everything. This post is part of that process…

Not only have these advances in photography helped me to create a visual archive for Dylan, they have enabled the production of instant images. Being able to record Dylan in the landscape and share this with him immediately has strengthened his sense of place and helped him to develop a sense of identity and belonging. This has been further helped by the ‘selfie’ option, which has allowed Dylan to locate himself in the landscape with others and has enabled him to take photographs himself, with minimum support. How marvellous that there have been all these developments in Dylan’s lifetime, I used to think to myself. Used to? Yes, because this has all changed. Suddenly (I suspect) and recently (I think). Although I can’t be sure – maybe I only noticed suddenly and recently and it had been brewing a while? I am having to re-think everything. This post is part of that process… My mobile phone is packed with photos, the vast majority involving Dylan in some way. They are records of places we have visited, mostly landscape but sometimes featuring one or both of us (sometimes ‘selfies’ but more often not) generally taken by me but a few by Dylan, my daughter or friends. The gallery is added to on a weekly basis, when Dylan comes for home visits, and more often during holidays and trips. But here’s a thing. The most recent photo of Dylan on my phone is a selfie of us at Cleethorpes, taken on New Year’s Day. Dylan has made numerous home visits, since then, and we have been on overnight trips and spent a week in Wales. But, except for one landscape shot taken in Wales on 21st April, there is no record on my phone of these visits.

My mobile phone is packed with photos, the vast majority involving Dylan in some way. They are records of places we have visited, mostly landscape but sometimes featuring one or both of us (sometimes ‘selfies’ but more often not) generally taken by me but a few by Dylan, my daughter or friends. The gallery is added to on a weekly basis, when Dylan comes for home visits, and more often during holidays and trips. But here’s a thing. The most recent photo of Dylan on my phone is a selfie of us at Cleethorpes, taken on New Year’s Day. Dylan has made numerous home visits, since then, and we have been on overnight trips and spent a week in Wales. But, except for one landscape shot taken in Wales on 21st April, there is no record on my phone of these visits. The photo in Wales (on the left) was taken to see if Dylan would allow me to use my camera phone after months of him objecting. How many months? At least five, maybe more. I can’t pinpoint exactly when it started. I wish I could because then I might be able to work out why. Looking back at the photos of Dylan on my phone immediately before New Year’s Day, he seems to be smiling and happy. There are fewer than in previous years, perhaps. Now, as I search my online records, I see that on 26th December I reflected to friends that Dylan seemed to ‘have become camera shy’ and reported that I’d shaved him in case he disliked his full beard. So, Dylan was already feeling uncomfortable about phone photographs in December?

The photo in Wales (on the left) was taken to see if Dylan would allow me to use my camera phone after months of him objecting. How many months? At least five, maybe more. I can’t pinpoint exactly when it started. I wish I could because then I might be able to work out why. Looking back at the photos of Dylan on my phone immediately before New Year’s Day, he seems to be smiling and happy. There are fewer than in previous years, perhaps. Now, as I search my online records, I see that on 26th December I reflected to friends that Dylan seemed to ‘have become camera shy’ and reported that I’d shaved him in case he disliked his full beard. So, Dylan was already feeling uncomfortable about phone photographs in December?  And now I think about it, perhaps that could explain the day I had to report an ‘incident’ during a home visit (such a rare occurrence that the care home manager commented to me that she was surprised to see the report). Dylan and I were completing a familiar and much-loved walk when he became distressed and started jumping wildly (one of Dylan’s anxiety behaviours) at the edge of a steep path. It was a difficult situation for me to manage and I was badly shaken, especially as I didn’t know what had triggered it. But now I remember that I had taken my phone out to photograph the valley. According to my diary that was 17th October. Could Dylan really have been anxious about photos as long ago as that? How much discomfort might I have put him through before he managed to communicate this to me?

And now I think about it, perhaps that could explain the day I had to report an ‘incident’ during a home visit (such a rare occurrence that the care home manager commented to me that she was surprised to see the report). Dylan and I were completing a familiar and much-loved walk when he became distressed and started jumping wildly (one of Dylan’s anxiety behaviours) at the edge of a steep path. It was a difficult situation for me to manage and I was badly shaken, especially as I didn’t know what had triggered it. But now I remember that I had taken my phone out to photograph the valley. According to my diary that was 17th October. Could Dylan really have been anxious about photos as long ago as that? How much discomfort might I have put him through before he managed to communicate this to me? Now, because I’m alert to Dylan’s discomfort, he only has to say ‘no, no’ and wave his hand. I thought that I had always asked Dylan for his consent before taking his picture, but I realise now that I probably did this in the same way that I ask my dad or daughter for permission to photograph them. Dylan needs to be given more opportunity to communicate consent or refusal than a neurotypical person because he doesn’t have access to the usual strategies, such as spoken language. Obviously, since Dylan has refused to be photographed I’ve stopped sharing pictures online and I’ve been giving some thought to archival material (such as on this blog) and reflecting on ethical and other implications. However, I’m not convinced that whatever is underlying this is quite as straightforward for Dylan…

Now, because I’m alert to Dylan’s discomfort, he only has to say ‘no, no’ and wave his hand. I thought that I had always asked Dylan for his consent before taking his picture, but I realise now that I probably did this in the same way that I ask my dad or daughter for permission to photograph them. Dylan needs to be given more opportunity to communicate consent or refusal than a neurotypical person because he doesn’t have access to the usual strategies, such as spoken language. Obviously, since Dylan has refused to be photographed I’ve stopped sharing pictures online and I’ve been giving some thought to archival material (such as on this blog) and reflecting on ethical and other implications. However, I’m not convinced that whatever is underlying this is quite as straightforward for Dylan… Dylan’s current objection to photography goes beyond my taking his picture; he objects to my taking any photographs at all. There are only 16 shots In my mobile phone gallery since I photographed the two of us on New Year’s Day. With the exception of the photo in Wales, they were all taken when Dylan wasn’t with me. Even if I reassure Dylan that I am not going to take a picture of him, he still says ‘no, no’ and waves his hands if I get my phone out. Sometimes he tries to grab the phone from me and once or twice he has become distressed enough for this to threaten to lead to the jumping which signals anxiety.

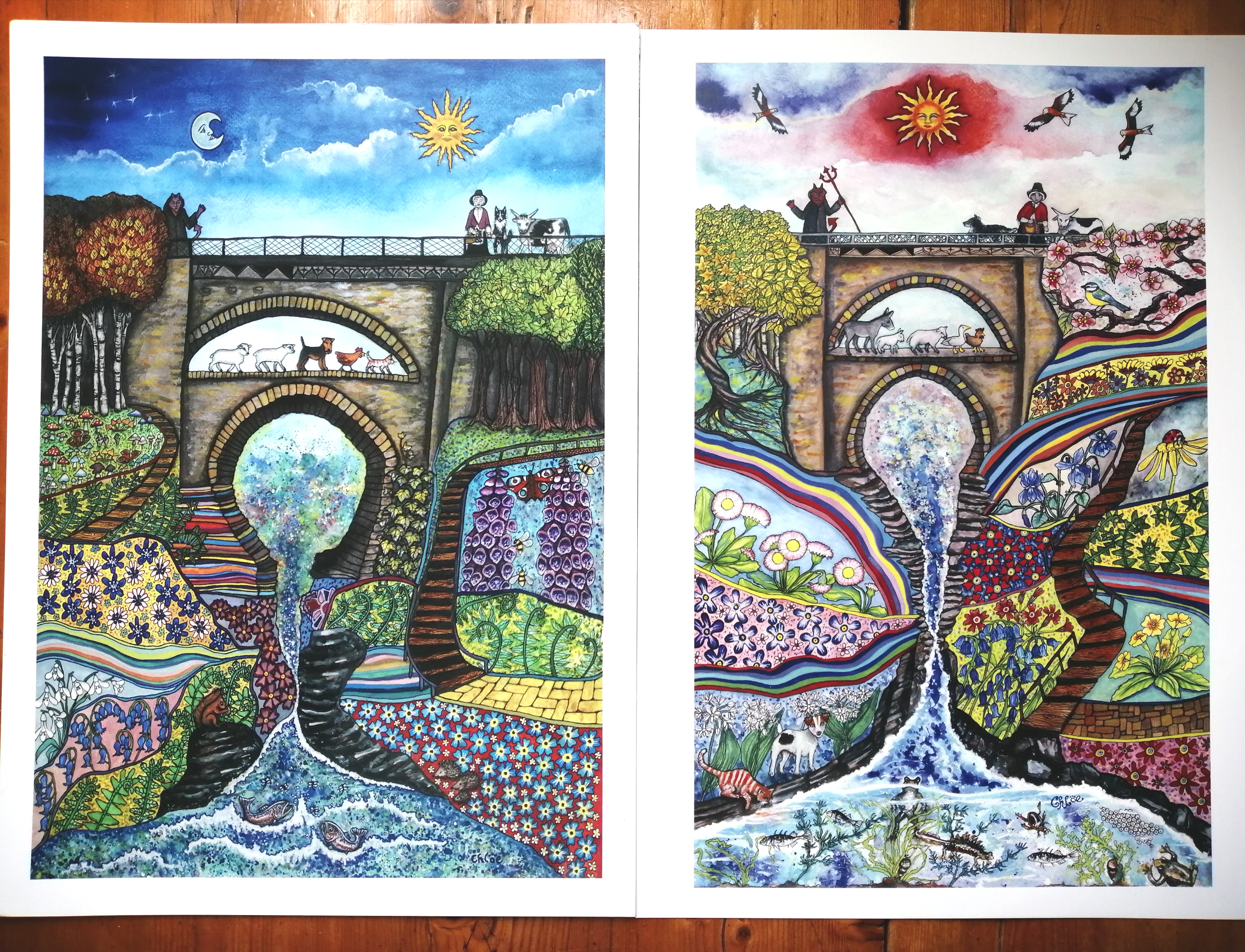

Dylan’s current objection to photography goes beyond my taking his picture; he objects to my taking any photographs at all. There are only 16 shots In my mobile phone gallery since I photographed the two of us on New Year’s Day. With the exception of the photo in Wales, they were all taken when Dylan wasn’t with me. Even if I reassure Dylan that I am not going to take a picture of him, he still says ‘no, no’ and waves his hands if I get my phone out. Sometimes he tries to grab the phone from me and once or twice he has become distressed enough for this to threaten to lead to the jumping which signals anxiety.  Obviously, this is a risk I have not been prepared to take for the sake of a photo of, for example, Devil’s Bridge at Pontarfynach. Our visit there at Easter was the highlight of Dylan’s holiday. Dylan was utterly transfixed by the chaos of water and stone and he lingered at the Punchbowl and viewing platforms on Jacob’s Ladder as long as I would let him. Previously, Dylan would have wanted me to photograph this magical place so that he could return to images of it whenever he wanted. ‘Do you want me to take a photograph of the water for you, Dylan?’ ‘No, no, no’. Of course, I could not risk Dylan jumping into the Mynach Falls. Serendipitously, on this occasion, a print of Devil’s Bridge was hanging in our holiday cottage and every evening Dylan would stand before it, entranced. Since we returned from our holiday I have bought a copy of the print (Clever Girl) and a sister piece (Spring) by the same artist, Chloe Rodenhurst, so that Dylan can continue to enjoy the visual world that speaks so eloquently to him (if no longer via photographs).

Obviously, this is a risk I have not been prepared to take for the sake of a photo of, for example, Devil’s Bridge at Pontarfynach. Our visit there at Easter was the highlight of Dylan’s holiday. Dylan was utterly transfixed by the chaos of water and stone and he lingered at the Punchbowl and viewing platforms on Jacob’s Ladder as long as I would let him. Previously, Dylan would have wanted me to photograph this magical place so that he could return to images of it whenever he wanted. ‘Do you want me to take a photograph of the water for you, Dylan?’ ‘No, no, no’. Of course, I could not risk Dylan jumping into the Mynach Falls. Serendipitously, on this occasion, a print of Devil’s Bridge was hanging in our holiday cottage and every evening Dylan would stand before it, entranced. Since we returned from our holiday I have bought a copy of the print (Clever Girl) and a sister piece (Spring) by the same artist, Chloe Rodenhurst, so that Dylan can continue to enjoy the visual world that speaks so eloquently to him (if no longer via photographs). I might not have risked photographing the Mynach Falls but I did conduct an experiment that week. One of the theories I’ve developed is that Dylan dislikes me using my phone rather than the phone camera. Could he be trying to sabotage my conversations with his sister? Maybe he doesn’t like the effect of speaker phone on language. Or perhaps Dylan resents any time I spend on my phone (checking for news and email) and wants my attention to himself. Quite right too. Or (a wilder hypothesis) could he have developed anxiety about my phone as a result of a specific incident? Dylan may, for example, have made a connection between my mobile phone and a Lateral Flow Test he had to take for Disney on Ice (due to a problem with the notification). That was in December which might fit with the Christmas/New Year dates (but wouldn’t explain the October incident I’ve recalled while writing this blog). To test whether Dylan’s protest is about my phone or my photography, I took my old digital camera on our trip to Wales.

I might not have risked photographing the Mynach Falls but I did conduct an experiment that week. One of the theories I’ve developed is that Dylan dislikes me using my phone rather than the phone camera. Could he be trying to sabotage my conversations with his sister? Maybe he doesn’t like the effect of speaker phone on language. Or perhaps Dylan resents any time I spend on my phone (checking for news and email) and wants my attention to himself. Quite right too. Or (a wilder hypothesis) could he have developed anxiety about my phone as a result of a specific incident? Dylan may, for example, have made a connection between my mobile phone and a Lateral Flow Test he had to take for Disney on Ice (due to a problem with the notification). That was in December which might fit with the Christmas/New Year dates (but wouldn’t explain the October incident I’ve recalled while writing this blog). To test whether Dylan’s protest is about my phone or my photography, I took my old digital camera on our trip to Wales. I was able to take 14 photographs that week, including one of Dylan under the Jubilee Arch at Hafod (which I won’t share). I would say that Dylan wasn’t super relaxed but he gave consent and seemed happy enough. It was for this reason I attempted to take a photo with my mobile phone on 21st April. Having used my Fujifilm all week, how would Dylan react to the iPhone? I took the shot but Dylan wasn’t at all happy about it and, given the terrain, I put my phone away. What do I surmise from this? It may be the phone, rather than the phone camera, which makes Dylan anxious, but I need more evidence. If it is the phone, then I have a not-insignificant problem. I need to be able to use my mobile in emergencies and for navigation. I should be able to take calls from friends and family if they need me. I have to be able to use digital apps (railcards for example) when we are in the community. And, importantly, I need to be able to record medical and other incidents for Dylan’s records.

I was able to take 14 photographs that week, including one of Dylan under the Jubilee Arch at Hafod (which I won’t share). I would say that Dylan wasn’t super relaxed but he gave consent and seemed happy enough. It was for this reason I attempted to take a photo with my mobile phone on 21st April. Having used my Fujifilm all week, how would Dylan react to the iPhone? I took the shot but Dylan wasn’t at all happy about it and, given the terrain, I put my phone away. What do I surmise from this? It may be the phone, rather than the phone camera, which makes Dylan anxious, but I need more evidence. If it is the phone, then I have a not-insignificant problem. I need to be able to use my mobile in emergencies and for navigation. I should be able to take calls from friends and family if they need me. I have to be able to use digital apps (railcards for example) when we are in the community. And, importantly, I need to be able to record medical and other incidents for Dylan’s records.  Recently, for example, Dylan sustained a cut on the head which I asked him if I could photograph with my phone. Dylan refused and the cut had to be photographed without Dylan’s consent by the care home. While not ideal, there will be other incidents and injuries, particularly given Dylan’s epilepsy, which need to be recorded in this way. I’m told that care home staff photograph Dylan using a variety of devices, including iPhones, but I don’t know whether this is with Dylan’s consent or if he has ever protested about it. Is it only my phone that Dylan objects to? I need more information. Meantime, I am trying to stay alert and open enough to hear what it is Dylan is trying to communicate and work out why. I’d be glad to hear from anyone who has experienced anything similar or has new ideas and fresh eyes.

Recently, for example, Dylan sustained a cut on the head which I asked him if I could photograph with my phone. Dylan refused and the cut had to be photographed without Dylan’s consent by the care home. While not ideal, there will be other incidents and injuries, particularly given Dylan’s epilepsy, which need to be recorded in this way. I’m told that care home staff photograph Dylan using a variety of devices, including iPhones, but I don’t know whether this is with Dylan’s consent or if he has ever protested about it. Is it only my phone that Dylan objects to? I need more information. Meantime, I am trying to stay alert and open enough to hear what it is Dylan is trying to communicate and work out why. I’d be glad to hear from anyone who has experienced anything similar or has new ideas and fresh eyes.  I’ve always prompted Dylan to verbalise key words in response to specific social situations. ‘Say Please Dylan’. ‘Dylan, can you say Hello?’ ‘Say Thank You Dylan’. ‘Dylan, say Bye Bye’. ‘Night Night, Dylan. Can you say Night Night?’ Dylan will sometimes produce one of these phrases spontaneously but usually they have to be scripted for him. In this way I scaffold the development of Dylan’s social as well as language skills, nudging him to respond appropriately to social cues.

I’ve always prompted Dylan to verbalise key words in response to specific social situations. ‘Say Please Dylan’. ‘Dylan, can you say Hello?’ ‘Say Thank You Dylan’. ‘Dylan, say Bye Bye’. ‘Night Night, Dylan. Can you say Night Night?’ Dylan will sometimes produce one of these phrases spontaneously but usually they have to be scripted for him. In this way I scaffold the development of Dylan’s social as well as language skills, nudging him to respond appropriately to social cues.  These cases of scripting are fairly straightforward. A more complicated example is my attempt to scaffold the word ‘sorry’ for Dylan. This is challenging not only because it’s difficult to predict the need to say sorry, but because it involves an understanding of cause and effect (the impact of our actions) empathy (how our actions make another person feel) and remorse (regret for our actions). It could be argued that adults with autism who lack capacity are incapable of understanding these concepts and thus are unable to offer a meaningful apology. Nonetheless, I script the word for Dylan:

These cases of scripting are fairly straightforward. A more complicated example is my attempt to scaffold the word ‘sorry’ for Dylan. This is challenging not only because it’s difficult to predict the need to say sorry, but because it involves an understanding of cause and effect (the impact of our actions) empathy (how our actions make another person feel) and remorse (regret for our actions). It could be argued that adults with autism who lack capacity are incapable of understanding these concepts and thus are unable to offer a meaningful apology. Nonetheless, I script the word for Dylan: Dylan was at home one weekend, happy enough but tight as a spring, pinballing around the house. ‘Slow down Dylan’ I shouted as I heard him clattering on the stairs, taking three steps at a time in his long stride, hooting like an owl. I was sweeping the fire out downstairs, preparing for our Saturday evening. Then, suddenly, a bang and a crash and a crack sent me running to investigate…

Dylan was at home one weekend, happy enough but tight as a spring, pinballing around the house. ‘Slow down Dylan’ I shouted as I heard him clattering on the stairs, taking three steps at a time in his long stride, hooting like an owl. I was sweeping the fire out downstairs, preparing for our Saturday evening. Then, suddenly, a bang and a crash and a crack sent me running to investigate… Sometimes it can feel as if the staffing situation at Dylan’s home is more challenging now than it was during the height of the pandemic. Although some care workers had to self-isolate during lockdowns, I don’t recall significant staff shortages. The Omicron mutation may be less deadly than previous variants, and resistance in the community higher, but the spread of the virus through the population has had a devastating impact on public and social services.

Sometimes it can feel as if the staffing situation at Dylan’s home is more challenging now than it was during the height of the pandemic. Although some care workers had to self-isolate during lockdowns, I don’t recall significant staff shortages. The Omicron mutation may be less deadly than previous variants, and resistance in the community higher, but the spread of the virus through the population has had a devastating impact on public and social services. Coal miners carried caged canaries into underground tunnels as the birds would alert them to the presence of noxious gases. I think of Dylan as a sort of ‘pit canary’ for the environments we have to negotiate in our daily lives. If a place or situation triggers ‘behaviours’ in him then It might suggest that there is something stressful about the circumstances which could potentially unsettle any of us.

Coal miners carried caged canaries into underground tunnels as the birds would alert them to the presence of noxious gases. I think of Dylan as a sort of ‘pit canary’ for the environments we have to negotiate in our daily lives. If a place or situation triggers ‘behaviours’ in him then It might suggest that there is something stressful about the circumstances which could potentially unsettle any of us.  Speaking of Arenas, I was relieved to be able to take Dylan to his beloved Disney-on-Ice at Sheffield Arena last month. It’s become an annual Christmas tradition for Dylan and one that he missed terribly in 2020 when it was cancelled due to Covid-19. I optimistically bought tickets for this year’s show and crossed my skates that it would go ahead.

Speaking of Arenas, I was relieved to be able to take Dylan to his beloved Disney-on-Ice at Sheffield Arena last month. It’s become an annual Christmas tradition for Dylan and one that he missed terribly in 2020 when it was cancelled due to Covid-19. I optimistically bought tickets for this year’s show and crossed my skates that it would go ahead.  In November Dylan thoroughly enjoyed an overnight stay at the Premier Inn in Cleethorpes. We have visited the resort regularly as it’s the closest coast to our home city but we have never stayed overnight. On previous day trips, Dylan has pushed and pulled and cajoled me to the Premier Inn so that he can stand and gaze at it. He was needless to say in high excitement that this time he got to go inside (with a pumpkin lantern and Doctor Who).

In November Dylan thoroughly enjoyed an overnight stay at the Premier Inn in Cleethorpes. We have visited the resort regularly as it’s the closest coast to our home city but we have never stayed overnight. On previous day trips, Dylan has pushed and pulled and cajoled me to the Premier Inn so that he can stand and gaze at it. He was needless to say in high excitement that this time he got to go inside (with a pumpkin lantern and Doctor Who).

The combination of a dog and Dylan is unthinkable. While there are moving ‘rescue narratives’ of therapy dogs who have transformed the lives of autistic children and adults, narratives of autism and dog anxiety are equally powerful. Dylan is absolutely terrified of dogs and I know from contact with other parents of autistic children he is not alone in this.

The combination of a dog and Dylan is unthinkable. While there are moving ‘rescue narratives’ of therapy dogs who have transformed the lives of autistic children and adults, narratives of autism and dog anxiety are equally powerful. Dylan is absolutely terrified of dogs and I know from contact with other parents of autistic children he is not alone in this. While the calmest of dogs is not enough for Dylan to unlearn fear, the thing that is guaranteed to send his anxiety sky high is an excitable dog. What Dylan cannot cope with is unpredictable behaviour. The reality is, however, that it is usually Dylan’s reactions to dogs which trigger their excitability, creating a situation where both Dylan and dog are leaping about, running in frantic circles, barking or shouting. ‘Worry, worry, worry’ Dylan yells repeatedly. This is Dylan echoing back the final part of the phrase I say to him when we encounter a dog: ’It’s alright, Dylan. Don’t worry’.

While the calmest of dogs is not enough for Dylan to unlearn fear, the thing that is guaranteed to send his anxiety sky high is an excitable dog. What Dylan cannot cope with is unpredictable behaviour. The reality is, however, that it is usually Dylan’s reactions to dogs which trigger their excitability, creating a situation where both Dylan and dog are leaping about, running in frantic circles, barking or shouting. ‘Worry, worry, worry’ Dylan yells repeatedly. This is Dylan echoing back the final part of the phrase I say to him when we encounter a dog: ’It’s alright, Dylan. Don’t worry’. But then, shortly before Dylan moved to residential care, Dylan had a curious encounter.

But then, shortly before Dylan moved to residential care, Dylan had a curious encounter. The friend who questioned my reasons for wanting a dog, in the immediate aftermath of Dylan moving to residential care, was right to do so. Since then I’ve realised that if I ever do get a dog it will need to be once I’ve retired; that (never having owned one) I would need to do a lot of research; and that Dylan would need careful introduction. Also, it would probably need to be a cockapoo called Coco.

The friend who questioned my reasons for wanting a dog, in the immediate aftermath of Dylan moving to residential care, was right to do so. Since then I’ve realised that if I ever do get a dog it will need to be once I’ve retired; that (never having owned one) I would need to do a lot of research; and that Dylan would need careful introduction. Also, it would probably need to be a cockapoo called Coco.

So I drove away thinking about our summer holiday and how best to support Dylan with this. I calculated that if I speeded up a bit with my marking I could take a couple of days off work later in the month. Added to a weekend, this would give Dylan four or five days at the coast. That would do it, surely? So later that week I booked a few days on the Yorkshire coast; while we won’t need a boat to get there, it is by the sea and we will be staying in a cottage.

So I drove away thinking about our summer holiday and how best to support Dylan with this. I calculated that if I speeded up a bit with my marking I could take a couple of days off work later in the month. Added to a weekend, this would give Dylan four or five days at the coast. That would do it, surely? So later that week I booked a few days on the Yorkshire coast; while we won’t need a boat to get there, it is by the sea and we will be staying in a cottage.

Perhaps, as Dylan’s understanding of time develops, he will need new strategies for managing it? Something which seemed to help Dylan in the past was his filofax. Although this didn’t have countdown charts and schedules in it, Dylan used it as an ‘object of reference’ for the management of time. He was aware, for example, that it contained the key information and cards he needs to access the activities he enjoys. He carried his filofax everywhere and would bring it to us if he wanted to request an activity. The filofax seemed to be such an important part of Dylan’s life, and so precious to him, that I was horrified when he destroyed it one night when he was anxious and upset about something which the support staff, on that occasion, were unable to fathom.

Perhaps, as Dylan’s understanding of time develops, he will need new strategies for managing it? Something which seemed to help Dylan in the past was his filofax. Although this didn’t have countdown charts and schedules in it, Dylan used it as an ‘object of reference’ for the management of time. He was aware, for example, that it contained the key information and cards he needs to access the activities he enjoys. He carried his filofax everywhere and would bring it to us if he wanted to request an activity. The filofax seemed to be such an important part of Dylan’s life, and so precious to him, that I was horrified when he destroyed it one night when he was anxious and upset about something which the support staff, on that occasion, were unable to fathom.

When I collected Dylan last weekend he wasn’t wearing his trademark Breton hat. I was shocked. Dylan is never without that hat; it stays fixed to his head when he is out of the house and he is very good at looking after it. Where is your hat, Dylan? I asked. He hasn’t ripped it, has he? I asked the member of staff who was with him. She didn’t know. In fact she hadn’t noticed that Dylan didn’t have it. But now I had mentioned it, Dylan was on it: lost it, he said, lost it. Then: find it, find it.

When I collected Dylan last weekend he wasn’t wearing his trademark Breton hat. I was shocked. Dylan is never without that hat; it stays fixed to his head when he is out of the house and he is very good at looking after it. Where is your hat, Dylan? I asked. He hasn’t ripped it, has he? I asked the member of staff who was with him. She didn’t know. In fact she hadn’t noticed that Dylan didn’t have it. But now I had mentioned it, Dylan was on it: lost it, he said, lost it. Then: find it, find it.

I very nearly didn’t take Dylan to Northumberland, however. I had made the booking in the new year, involving Dylan in the selection of the cottage. Our annual summer holiday is very important to Dylan and (after Christmas) the highlight of his year. Apart from the year prior to moving into residential care, when Dylan’s behaviour had been very challenging and I was advised not to take him, Dylan and I have enjoyed a holiday together every year. So it was with some concern, on the run up to this year’s trip, that I watched as Dylan grew increasingly unsettled.

I very nearly didn’t take Dylan to Northumberland, however. I had made the booking in the new year, involving Dylan in the selection of the cottage. Our annual summer holiday is very important to Dylan and (after Christmas) the highlight of his year. Apart from the year prior to moving into residential care, when Dylan’s behaviour had been very challenging and I was advised not to take him, Dylan and I have enjoyed a holiday together every year. So it was with some concern, on the run up to this year’s trip, that I watched as Dylan grew increasingly unsettled. A couple of nights before we were due to go on holiday there was a major incident. On this occasion Dylan was distressed for a significant period of time and destroyed a number of his things. There had been an incident earlier in the week and I had ordered replacements but they hadn’t yet arrived (this was before I had decided to stop re-buying DVDs). Dylan must have been frustrated by not being able to work his emotions out on his favourite DVDs so switched his attention to an alternative which, on this particular night, was his Filofax.

A couple of nights before we were due to go on holiday there was a major incident. On this occasion Dylan was distressed for a significant period of time and destroyed a number of his things. There had been an incident earlier in the week and I had ordered replacements but they hadn’t yet arrived (this was before I had decided to stop re-buying DVDs). Dylan must have been frustrated by not being able to work his emotions out on his favourite DVDs so switched his attention to an alternative which, on this particular night, was his Filofax. Residential homes for adults with complex needs are busy and sometimes chaotic places. Although they are routinised they are also unpredictable environments as the individual needs of residents emerge and require response. For Dylan – who hates noise and has very low tolerance of others – this must be a challenging and sometimes stressful environment. The mix of residents in a care home is not something any individual has control over – they are a cluster rather than a group – and there will inevitably be clashes of interest and personality.

Residential homes for adults with complex needs are busy and sometimes chaotic places. Although they are routinised they are also unpredictable environments as the individual needs of residents emerge and require response. For Dylan – who hates noise and has very low tolerance of others – this must be a challenging and sometimes stressful environment. The mix of residents in a care home is not something any individual has control over – they are a cluster rather than a group – and there will inevitably be clashes of interest and personality. My daughter is about to move into shared university housing and I’ve been chatting to her about this over the summer and recalling my own ‘group living’ days. While not wanting to put my daughter off, I couldn’t help but be honest with her the other day: ‘you know what, darling? I hated it.’

My daughter is about to move into shared university housing and I’ve been chatting to her about this over the summer and recalling my own ‘group living’ days. While not wanting to put my daughter off, I couldn’t help but be honest with her the other day: ‘you know what, darling? I hated it.’ As I’ve mentioned

As I’ve mentioned  But last week there was an accident; Dylan jumped so hard that he either landed awkwardly on his ankle or caught it on furniture. When I received an email to say that Dylan had hurt his ankle while jumping I wasn’t surprised in the sense that a jumping-related incident has been an accident waiting to happen for years. I was a bit alarmed, however, by the severity of the injury and the implications for Dylan. It took several phone calls and emails to reassure me that I didn’t need to go rushing to the home to see Dylan myself; there was nothing I could do that wasn’t already being done to support him. And although the photograph of Dylan’s ankle was a bit of a shock, it was helpful .

But last week there was an accident; Dylan jumped so hard that he either landed awkwardly on his ankle or caught it on furniture. When I received an email to say that Dylan had hurt his ankle while jumping I wasn’t surprised in the sense that a jumping-related incident has been an accident waiting to happen for years. I was a bit alarmed, however, by the severity of the injury and the implications for Dylan. It took several phone calls and emails to reassure me that I didn’t need to go rushing to the home to see Dylan myself; there was nothing I could do that wasn’t already being done to support him. And although the photograph of Dylan’s ankle was a bit of a shock, it was helpful . Happily Dylan accepted the changes to his programme. He also tolerated the application of anaesthetic gel and a support bandage in the days after the injury. I think Dylan grasped some of the implications of his injury and perhaps even had a basic understanding of cause and effect in relation to the behaviour which had caused it. What I didn’t believe, however, was that this would be enough to prevent Dylan from jumping again. On the contrary, I suggested to staff, wasn’t it likely that Dylan would be more prone to jumping due to his frustration at the situation? As far as I was concerned, there was a real danger that Dylan would damage his already-weakened ankle by jumping on it. And even if he didn’t, I said to the care home manager, the incident had made me realise that we had to do something about Dylan’s jumping. I didn’t want this to happen again.

Happily Dylan accepted the changes to his programme. He also tolerated the application of anaesthetic gel and a support bandage in the days after the injury. I think Dylan grasped some of the implications of his injury and perhaps even had a basic understanding of cause and effect in relation to the behaviour which had caused it. What I didn’t believe, however, was that this would be enough to prevent Dylan from jumping again. On the contrary, I suggested to staff, wasn’t it likely that Dylan would be more prone to jumping due to his frustration at the situation? As far as I was concerned, there was a real danger that Dylan would damage his already-weakened ankle by jumping on it. And even if he didn’t, I said to the care home manager, the incident had made me realise that we had to do something about Dylan’s jumping. I didn’t want this to happen again. Developing the details in Dylan’s care plan (for staff) and schedules (for Dylan) are strategies which focus on communication. There is nothing surprising or new here; it has been clear from the beginning of bouncing that underneath the behaviour lies Dylan’s deep frustration at being unable to communicate his needs and desires. We rely so heavily on the spoken and written word to communicate that I imagine whatever we do and however much we try, we will never be able to take away Dylan’s frustration entirely. As well as it being impossible to have pictures/symbols available for every eventuality (even digitally), Dylan’s significant intellectual disability means that he cannot always comprehend the nuance of communication through imagery.

Developing the details in Dylan’s care plan (for staff) and schedules (for Dylan) are strategies which focus on communication. There is nothing surprising or new here; it has been clear from the beginning of bouncing that underneath the behaviour lies Dylan’s deep frustration at being unable to communicate his needs and desires. We rely so heavily on the spoken and written word to communicate that I imagine whatever we do and however much we try, we will never be able to take away Dylan’s frustration entirely. As well as it being impossible to have pictures/symbols available for every eventuality (even digitally), Dylan’s significant intellectual disability means that he cannot always comprehend the nuance of communication through imagery. I’ve written

I’ve written