Something has happened since I posted at new year. It’s pretty big. When she heard, my friend Jo said: you don’t suppose this is about the car, do you? Surely not, I replied. That would be vindictive. More about that later. First, a bit of backstory about the (seemingly) small issue of Dylan’s car.

Breakdown

In my last post I mentioned that Dylan and I took the train for our new year trip as I was nervous about using my car, which had failed to start twice. Although I sorted my Skoda out, it was a wake-up call.

In my last post I mentioned that Dylan and I took the train for our new year trip as I was nervous about using my car, which had failed to start twice. Although I sorted my Skoda out, it was a wake-up call.

Some years ago, I realised the car I drive needs to be as reliable as possible so as to limit the chance of breaking down while transporting Dylan. Supporting Dylan at weekends typically involves 150 miles of driving and holidays significantly more. My local garage and mechanic have looked after us well, sourcing low mileage, ex-Motability cars, just out of warranty, as soon as my milometer hits the 50k mark (which experience has taught me is when things start to go wrong). My Skoda’s recent protests happened right on cue, in the high 40,000s.

This time, however, I’m in no position to replace it. While there are many benefits to being partially retired, money isn’t one of them. There’s no capacity in my current circumstances for trading in my car to meet Dylan’s needs. And changing the Skoda would be for Dylan not me: while I don’t relish the thought of breaking down, I’d run the risk if it was just me. This was a financial consideration I hadn’t considered when I gave up working full-time. What do other families of disabled adults do, I wondered?

Motability

And then of course I realised – the mobility component of a disabled person’s Personal Independence Payment (PIP) can be used for the hire cost of a Motability car. Not everyone who gets PIP qualifies for the mobility allowance, but Dylan has always received it. I’ve never previously applied for a Motability car as Dylan was either living at home (where two cars seemed pointless) or in a care setting with ‘pool cars’. Instead of spending Dylan’s benefit money on a Motability car, I used it to support his trips.

Now, however, the scheme appeared to offer an elegant solution. Dylan could keep a Motability car at the care home, and I would only need to use my car to drive there and back, leaving my car at the care home while Dylan and I used the Motability car. That would ensure Dylan was transported safely and reduce the wear and tear on my Skoda.

Getting a Motability car would also be a happy solution to a problem I’d only recently identified. Last October, when I asked the care home manager why Dylan seemed to be getting only limited exercise during the week, I was told there were times when a pool car wasn’t available. As there were only a limited number of cars to share between residents, if Dylan missed his scheduled slot, his outing had to be cancelled. So, two problems solved.

Nissan Joke

When I entered my search criteria on the Motability site it suggested a Nissan Juke. This made me smile. I’d had to hire cars for trips with Dylan for a while the last time I changed my car. I’d cursed the Juke I drove one weekend for its blind spot. Nissan Joke, I called it.

When I entered my search criteria on the Motability site it suggested a Nissan Juke. This made me smile. I’d had to hire cars for trips with Dylan for a while the last time I changed my car. I’d cursed the Juke I drove one weekend for its blind spot. Nissan Joke, I called it.

The algorithms were having a laugh. It was probably because I’d selected CD player, I decided. Old technology, my car salesman told me when I asked why my new Skoda didn’t have one. But old technology is essential for Dylan who needs to choose CDs and DVDs by the picture on the box. Streaming doesn’t work for him. The jewel case is part of the pleasure. Dylan opens it slowly and carefully, pausing to admire the glint of the disc.

I curse the lack of a CD player in my current car regularly. I’ve bought an Oakbrook AUX plug-in, but it eats batteries and (contrary to promises) jumps constantly. And I can’t adjust it while I’m driving: no skipping the tracks that hurt Dylan’s ears or changing a CD without stopping. I’m sorry, Dylan, I say repeatedly. Rubbish isn’t it. I promise that next time mummy will get a car with a CD player. But would I really choose a Nissan Joke for a CD player?

Test Drive

Only in the old models, Peter says, when I ask where the CD player is. 8th January. I’m sitting in a blue Nissan Juke on the forecourt of Bristol Street Motors, scanning the controls. I get in the back, try to assess whether Dylan would be safe. I climb back in the driver’s seat. That’s not very good, I say. No CD player is probably a deal breaker. You won’t find any new car with one, Peter tells me. Old technology. May as well drive it, I say. As I’m here.

I can’t have been the only person who was troubled by that blind spot. The car has a ‘blind spot warning system’ which pings when someone drives into it. I don’t know what’s worse, I say to Peter, as I accelerate up one of Sheffield’s wicked hills: the pinging or the blind spot. You can disable it if it annoys you, he reassures me.

Could I have one with a handbrake, I ask, when we’re back at the showroom. I need the controls to be as simple as possible. Some of the care workers are young. They won’t have driven anything like this. I don’t want them to be thinking about the car. They need to stay focused on my son. Sure, Peter says. We can request adaptations. Anything you want. Except for a CD player. It’s disappointing, I say. But I guess it’s OK. I just need to check with the care home. I’ll ring to confirm. I’m sure it will be fine.

Seven Seats

But when I checked with the manager, there was a problem. It would need to be a 7-seater vehicle. Next time I collected Dylan, I might want to have a look at one in the car park that belongs to another resident. Something like that would be good please. I didn’t understand. Why, I asked. Dylan requires an empty row to be left between him and the driver, she explained. We usually transport him in the back of a people carrier.

But when I checked with the manager, there was a problem. It would need to be a 7-seater vehicle. Next time I collected Dylan, I might want to have a look at one in the car park that belongs to another resident. Something like that would be good please. I didn’t understand. Why, I asked. Dylan requires an empty row to be left between him and the driver, she explained. We usually transport him in the back of a people carrier.

I was aghast. This was a conversation with too many starting points. In no particular order, I didn’t want to be driving a people carrier on single track roads in Wales or parking one on my busy city street. And I certainly didn’t want to have to fill one up with petrol from Dylan’s much reduced weekly benefit. Dylan was only ever transported with one or two other adults – how could a 7-seater car be justified? Had the manager not heard of climate change?

Besides (and actually this is the starting point) it just wasn’t right. Dylan loves driving. With hardly any multi-syllable words, Dylan pronouncing ‘gearstick’ with a flourish (laughing) is one of my miracles. Cars are for feeling safe and for the gift of language. This is where Dylan initiates conversation, shouting ‘cows’ or ‘sheep’ at passing fields; telling me ‘at way’ (pointing with his arm) is ‘boom’ (Kelham Island Museum); ‘at way’ is ‘F’man Sam’ (the Emergency Services Museum); and ’at way’ is ‘Log’ (where he went for respite as a child). He verbalises (as best he can) swimming pool, MacDonalds, tram, water, and cafe. He reminds me, as we pass Record Collector, that we don’t have ‘Heap’ (Speak for Yourself). But Oxfam has ‘books’ and ‘DDs’. This is car-based communication through which Dylan shares his world. It is declarative and imperative. This is as good as conversation with Dylan gets.

Let me get this right, I say. You’re telling me that Dylan is usually transported in the back of a people carrier, separated from his support workers? Always, the manager confirms. At least a row of seats between. It’s in his risk assessment, she explains, due to some incidents.

Incarceration

When I asked for the evidence, it appeared there had been 13 ‘incidents’ in the nine years that Dylan had lived at the setting. I don’t mean to trivialise the data. You can’t afford to take a single risk with transportation I know. Except that when I looked at the incidents, they weren’t about the car. The car was the site of protest at the end of an unsatisfactory trip. They were protests about an activity coming to an end before Dylan was ready. An unexpected transition. A takeaway meal he was disappointed with. Perhaps (I speculated) music on the radio that distressed him, a misunderstood attempt at communication or (it occurred to me with a feeling of sadness) him simply feeling isolated and alone.

They’re using it as a prison van, mum, my daughter observed. It’s about containment. Transporting Dylan as if he’s dangerous. Stick him in the back. Shut the door. They need the people carrier to lock Dylan down when he protests. He’s not compliant enough for them. You should be proud of him, mum.

Next day, I emailed the manager that I wouldn’t be getting a people carrier. Dylan didn’t need one. I would order a Nissan Juke – significantly chunkier than my Skoda and hopefully a good compromise. She replied that Dylan wouldn’t be able to use it while he was with them. Staff would not feel comfortable driving it. Could she be serious, I asked Jo, who has experience of the sector. Probably, she replied. Everything is driven by risk assessment. This is one argument you’re probably not going to win.

Independence

I decided to go ahead. I would have preferred to act in partnership with the care home, but couldn’t find common ground with this one. It was a shame the car would stand idle during the week, but I’d probably be driving it more than them, based on Dylan’s short trips out during the week. If the car didn’t get used enough, it could go back at the end of the hire agreement. Or when I could afford to replace my Skoda. So for the first time since Dylan moved to residential care, I acted independently. Good for you, mum, my daughter said. Ironically, I replied, it’s Dylan’s independence it was supposed to promote, not mine.

I decided to go ahead. I would have preferred to act in partnership with the care home, but couldn’t find common ground with this one. It was a shame the car would stand idle during the week, but I’d probably be driving it more than them, based on Dylan’s short trips out during the week. If the car didn’t get used enough, it could go back at the end of the hire agreement. Or when I could afford to replace my Skoda. So for the first time since Dylan moved to residential care, I acted independently. Good for you, mum, my daughter said. Ironically, I replied, it’s Dylan’s independence it was supposed to promote, not mine.

Breakdown

Two weeks after the manager tried to persuade me to get a people carrier, the National Autistic Society held a meeting at which it was agreed to terminate Dylan’s placement, with three-month’s notice. I didn’t know about the meeting, and I wasn’t told about the eviction until two weeks after the decision had been made.

‘You don’t suppose this is about the car, do you?’ Jo asked when I told her. We couldn’t imagine why the manager would have tried to influence the choice of car if she was about to terminate Dylan’s placement. But neither did we think the car was what this was about. Surely not. That would be vindictive.

Blue Lining

I took delivery of Dylan’s Juke a couple of weeks ago, a bright blue moment in the midst of a stressful time (though not for Dylan, who isn’t aware of any of this). Nissan hadn’t fitted a mechanical handbrake as requested. Don’t worry, I told Peter. It will be fine. The situation is a little different to when I ordered it. I don’t suppose by some miracle it has a CD player, I asked. Peter laughed. Only joking, I said. I’ve bought a CD player that runs off the car battery. Dylan should be able to operate it from the back. It will give him some independence. He’s going to love that.

I took delivery of Dylan’s Juke a couple of weeks ago, a bright blue moment in the midst of a stressful time (though not for Dylan, who isn’t aware of any of this). Nissan hadn’t fitted a mechanical handbrake as requested. Don’t worry, I told Peter. It will be fine. The situation is a little different to when I ordered it. I don’t suppose by some miracle it has a CD player, I asked. Peter laughed. Only joking, I said. I’ve bought a CD player that runs off the car battery. Dylan should be able to operate it from the back. It will give him some independence. He’s going to love that.

While we haven’t yet reached the silver lining of eviction (more about that in later posts) we have a sparkly blue lining. Dylan seems comfortable in his new car and to enjoy being in charge of the music. He’s developed an unexpected interest in the Sat Nav and – also against expectation – a couple of staff have taken Dylan for a spin in his new car: ‘he sat lovely throughout the journey’, one of them told me. ‘I actually liked him sat closer, its easier for us to have a natter.’

In my last post,

In my last post,  I was minded of Dylan’s phone-phobia recently while reading a Jonathan Franzen essay on Sherry Turkle (a ‘technology skeptic who was once a believer’). Children, Turkle writes, ‘can’t get their parents’ attention away from their phones’. The decline in interaction within a family, Turkle suggests, inflicts social, emotional and psychological damage on children, specifically ‘the development of trust and self-esteem’ and ‘the capacity for empathy, friendship and intimacy’. Parents need to ‘step up to their responsibilities as mentors’, Turkle argues, and practice the patient art of conversation with their children rather than demonstrating parental love (as Franzen puts it) ‘by snapping lots of pictures and posting them on Facebook’.

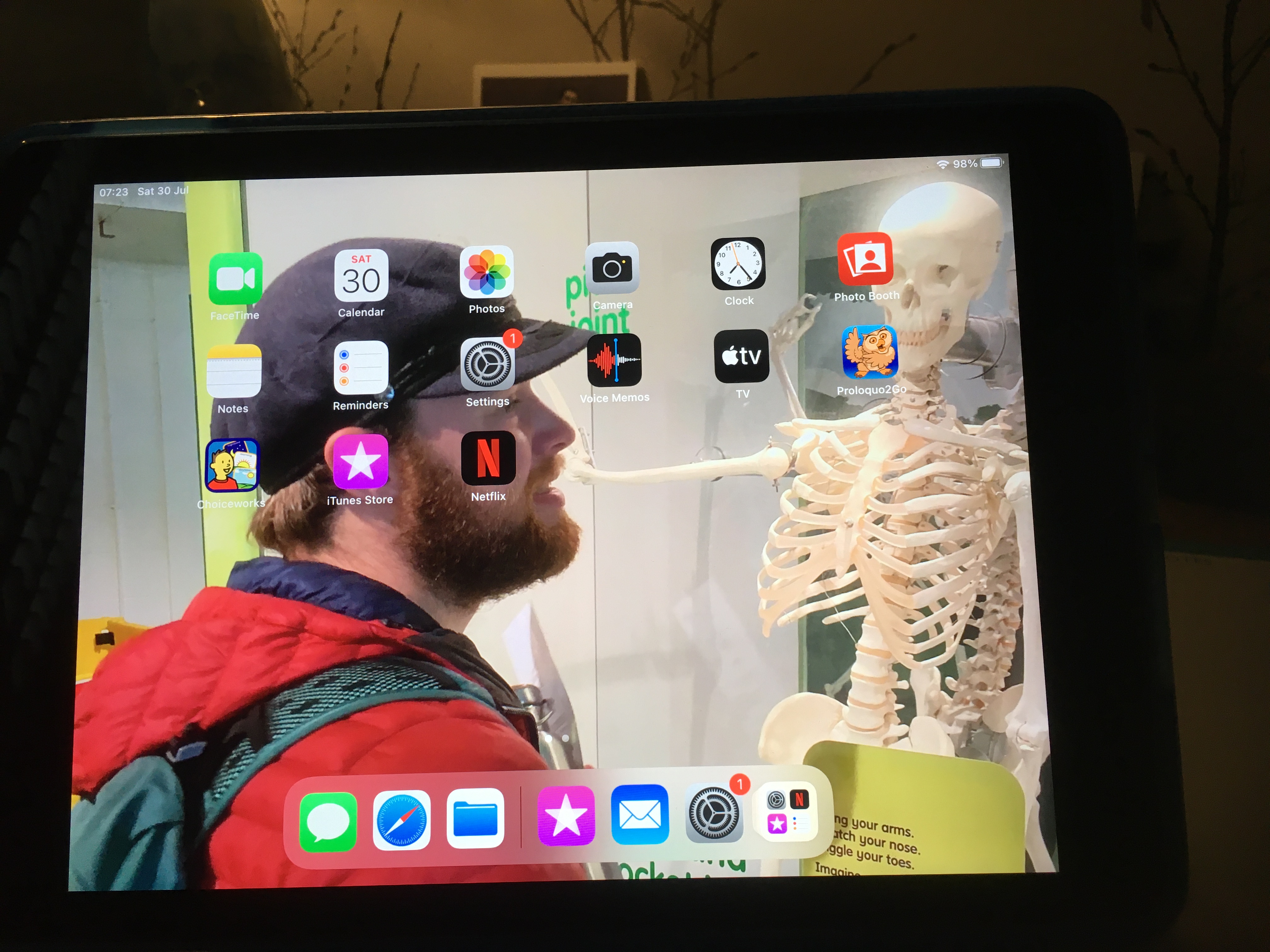

I was minded of Dylan’s phone-phobia recently while reading a Jonathan Franzen essay on Sherry Turkle (a ‘technology skeptic who was once a believer’). Children, Turkle writes, ‘can’t get their parents’ attention away from their phones’. The decline in interaction within a family, Turkle suggests, inflicts social, emotional and psychological damage on children, specifically ‘the development of trust and self-esteem’ and ‘the capacity for empathy, friendship and intimacy’. Parents need to ‘step up to their responsibilities as mentors’, Turkle argues, and practice the patient art of conversation with their children rather than demonstrating parental love (as Franzen puts it) ‘by snapping lots of pictures and posting them on Facebook’. Dylan has been using an iPad for years, primarily to access CDs and films he has purchased and downloaded and which he can watch offline. Previously, Dylan had portable DVD and CD players for this purpose but the iPad proved a better option practically and for promoting independence. Although initially intended for use during journeys and holidays, Dylan became increasingly attached to his iPad and built it into his daily routine, often preferring it to his TV or over other activities.

Dylan has been using an iPad for years, primarily to access CDs and films he has purchased and downloaded and which he can watch offline. Previously, Dylan had portable DVD and CD players for this purpose but the iPad proved a better option practically and for promoting independence. Although initially intended for use during journeys and holidays, Dylan became increasingly attached to his iPad and built it into his daily routine, often preferring it to his TV or over other activities. It is very hard to remove something from an adult, even when they lack the capacity to make decisions and need someone to act in their best interests. Dylan had been using an iPad for years and it had a key role in his life. I was aware that in removing it I could create more problems than I solved. The iPad, however, was itself the source of some of the difficulties which Dylan was encountering.

It is very hard to remove something from an adult, even when they lack the capacity to make decisions and need someone to act in their best interests. Dylan had been using an iPad for years and it had a key role in his life. I was aware that in removing it I could create more problems than I solved. The iPad, however, was itself the source of some of the difficulties which Dylan was encountering. What the recent problem with the iPad has demonstrated is that, given the built-in obstacles in the technology, Dylan requires support to use it. Dylan generally recognises when he needs support with something language-based and will request this. However, the personal usage data suggests that Dylan had been spending significant amounts of time on his iPad. The reality is that if staff are not available (or able) to support Dylan with the technology, rather than a resource it becomes a source of frustration and anger, leading both the technology and Dylan to breakdown.

What the recent problem with the iPad has demonstrated is that, given the built-in obstacles in the technology, Dylan requires support to use it. Dylan generally recognises when he needs support with something language-based and will request this. However, the personal usage data suggests that Dylan had been spending significant amounts of time on his iPad. The reality is that if staff are not available (or able) to support Dylan with the technology, rather than a resource it becomes a source of frustration and anger, leading both the technology and Dylan to breakdown.  At the time of writing (11 weeks after I confiscated the iPad) there is some evidence to suggest that the iPad had become a source of distress for Dylan rather than a support; certainly there has been a reduction in the total number of incidents when Dylan has become upset at the care home. I’ve been most struck, however, by the ease with which Dylan has accepted the change. Just as I quickly got used to life without my camera phone, so Dylan has adapted to life without his iPad. He asked about it a few times in the early days but hasn’t mentioned it (at least to me) for weeks.

At the time of writing (11 weeks after I confiscated the iPad) there is some evidence to suggest that the iPad had become a source of distress for Dylan rather than a support; certainly there has been a reduction in the total number of incidents when Dylan has become upset at the care home. I’ve been most struck, however, by the ease with which Dylan has accepted the change. Just as I quickly got used to life without my camera phone, so Dylan has adapted to life without his iPad. He asked about it a few times in the early days but hasn’t mentioned it (at least to me) for weeks.  Last semester I was asked to take a seminar group for a module which focuses on psychological perspectives on educational processes. I don’t usually teach on the module and I found the opportunity interesting and often valuable. One thing I was struck by, however, was how often mothers are blamed for poor educational outcomes.

Last semester I was asked to take a seminar group for a module which focuses on psychological perspectives on educational processes. I don’t usually teach on the module and I found the opportunity interesting and often valuable. One thing I was struck by, however, was how often mothers are blamed for poor educational outcomes. Most mothers with a child who has been diagnosed autistic hear about Bruno Bettelheim’s ‘refrigerator mothers’ at some point. Even though we are assured his work is now discredited, for the mother of a newly-diagnosed child it is very difficult to encounter Bettelheim’s claims. I certainly experienced them as cruel following Dylan’s diagnosis: I was doing everything I could to support my child, yet here I was being framed as the problem.

Most mothers with a child who has been diagnosed autistic hear about Bruno Bettelheim’s ‘refrigerator mothers’ at some point. Even though we are assured his work is now discredited, for the mother of a newly-diagnosed child it is very difficult to encounter Bettelheim’s claims. I certainly experienced them as cruel following Dylan’s diagnosis: I was doing everything I could to support my child, yet here I was being framed as the problem. As the mother of a non-verbal autistic man I find it useful and often illuminating to hear the testimony of autistic adults who self-advocate. Their voices give me new ways of thinking about Dylan and how he might experience the world. The demand by autistic self-advocates for ‘nothing about us that isn’t by us’, however, challenges parents (such as myself) who advocate for and on behalf of a son or daughter.

As the mother of a non-verbal autistic man I find it useful and often illuminating to hear the testimony of autistic adults who self-advocate. Their voices give me new ways of thinking about Dylan and how he might experience the world. The demand by autistic self-advocates for ‘nothing about us that isn’t by us’, however, challenges parents (such as myself) who advocate for and on behalf of a son or daughter. Some academics (mothers of disabled children themselves) have questioned the assumptions which have been made about the role of parents in a disabled child’s life. Ferguson (2001) argues that parents carry their child’s impairment as part of their own lived experience and are therefore well placed to advocate for their disabled children and bring about positive change in their lives. Similarly Kelly (2005) observes that parents ‘act as experiencers, interpreters and agents’ through their intimate connection to the experience of their disabled child. Parents’ embodied experience of care-giving is not ‘second-hand knowledge’ of disability, Kelly argues, but rather a ‘partial knowledge’ which allows parents to share some of their child’s experience and meaning-making.

Some academics (mothers of disabled children themselves) have questioned the assumptions which have been made about the role of parents in a disabled child’s life. Ferguson (2001) argues that parents carry their child’s impairment as part of their own lived experience and are therefore well placed to advocate for their disabled children and bring about positive change in their lives. Similarly Kelly (2005) observes that parents ‘act as experiencers, interpreters and agents’ through their intimate connection to the experience of their disabled child. Parents’ embodied experience of care-giving is not ‘second-hand knowledge’ of disability, Kelly argues, but rather a ‘partial knowledge’ which allows parents to share some of their child’s experience and meaning-making. Although I am uncomfortable with the way in which it is the mother, rather than father, who is subject to surveillance and criticism in relation to the ability to parent a disabled child, I am not averse to critical feedback and scrutiny. I often wish it were kinder, more supportive and more sympathetic. I would also prefer those without experience of parenting (even if they are themselves autistic) to acknowledge their own partial knowledge. Sanchez, in the post referred to above, makes some helpful observations and suggestions for building bridges between the ‘warring factions’ of autism parents and autistic adults.

Although I am uncomfortable with the way in which it is the mother, rather than father, who is subject to surveillance and criticism in relation to the ability to parent a disabled child, I am not averse to critical feedback and scrutiny. I often wish it were kinder, more supportive and more sympathetic. I would also prefer those without experience of parenting (even if they are themselves autistic) to acknowledge their own partial knowledge. Sanchez, in the post referred to above, makes some helpful observations and suggestions for building bridges between the ‘warring factions’ of autism parents and autistic adults.

I very nearly didn’t take Dylan to Northumberland, however. I had made the booking in the new year, involving Dylan in the selection of the cottage. Our annual summer holiday is very important to Dylan and (after Christmas) the highlight of his year. Apart from the year prior to moving into residential care, when Dylan’s behaviour had been very challenging and I was advised not to take him, Dylan and I have enjoyed a holiday together every year. So it was with some concern, on the run up to this year’s trip, that I watched as Dylan grew increasingly unsettled.

I very nearly didn’t take Dylan to Northumberland, however. I had made the booking in the new year, involving Dylan in the selection of the cottage. Our annual summer holiday is very important to Dylan and (after Christmas) the highlight of his year. Apart from the year prior to moving into residential care, when Dylan’s behaviour had been very challenging and I was advised not to take him, Dylan and I have enjoyed a holiday together every year. So it was with some concern, on the run up to this year’s trip, that I watched as Dylan grew increasingly unsettled. A couple of nights before we were due to go on holiday there was a major incident. On this occasion Dylan was distressed for a significant period of time and destroyed a number of his things. There had been an incident earlier in the week and I had ordered replacements but they hadn’t yet arrived (this was before I had decided to stop re-buying DVDs). Dylan must have been frustrated by not being able to work his emotions out on his favourite DVDs so switched his attention to an alternative which, on this particular night, was his Filofax.

A couple of nights before we were due to go on holiday there was a major incident. On this occasion Dylan was distressed for a significant period of time and destroyed a number of his things. There had been an incident earlier in the week and I had ordered replacements but they hadn’t yet arrived (this was before I had decided to stop re-buying DVDs). Dylan must have been frustrated by not being able to work his emotions out on his favourite DVDs so switched his attention to an alternative which, on this particular night, was his Filofax. Residential homes for adults with complex needs are busy and sometimes chaotic places. Although they are routinised they are also unpredictable environments as the individual needs of residents emerge and require response. For Dylan – who hates noise and has very low tolerance of others – this must be a challenging and sometimes stressful environment. The mix of residents in a care home is not something any individual has control over – they are a cluster rather than a group – and there will inevitably be clashes of interest and personality.

Residential homes for adults with complex needs are busy and sometimes chaotic places. Although they are routinised they are also unpredictable environments as the individual needs of residents emerge and require response. For Dylan – who hates noise and has very low tolerance of others – this must be a challenging and sometimes stressful environment. The mix of residents in a care home is not something any individual has control over – they are a cluster rather than a group – and there will inevitably be clashes of interest and personality. My daughter is about to move into shared university housing and I’ve been chatting to her about this over the summer and recalling my own ‘group living’ days. While not wanting to put my daughter off, I couldn’t help but be honest with her the other day: ‘you know what, darling? I hated it.’

My daughter is about to move into shared university housing and I’ve been chatting to her about this over the summer and recalling my own ‘group living’ days. While not wanting to put my daughter off, I couldn’t help but be honest with her the other day: ‘you know what, darling? I hated it.’