I grew up in England during the 70s and 80s in the era of superpower politics. It was a nervous time; as East and West squared up to each other the threat of nuclear warfare appeared real. Or at least that is how, as a teenager, I perceived the world.

I grew up in England during the 70s and 80s in the era of superpower politics. It was a nervous time; as East and West squared up to each other the threat of nuclear warfare appeared real. Or at least that is how, as a teenager, I perceived the world.

During adolescence my interest in politics was both empowering and a source of anxiety. In the early 80s, under the leadership of Thatcher, Reagan and a trio of old guard Presidents of the USSR (Brezhnev, Andropov and Chernenko) superpower politics reached new levels of hubris. I feared that in a fit of pique a President or Prime Minister would press one of the buttons located (it was said) in Downing Street, the White House and the Kremlin. These, we were told, would launch the missiles which would trigger a global nuclear war.

If it’s a little hard for me to think myself back to that time now I need only remember the publication in 1982 of When the Wind Blows, Raymond Briggs’ graphic novel about nuclear war (later released as an animated film). This was followed in 1984 by Barry Hines’ Threads with its nightmare vision of a post-nuclear world; Threads would have the additional impact on my nervous heart of having been filmed in my hometown.

If it’s a little hard for me to think myself back to that time now I need only remember the publication in 1982 of When the Wind Blows, Raymond Briggs’ graphic novel about nuclear war (later released as an animated film). This was followed in 1984 by Barry Hines’ Threads with its nightmare vision of a post-nuclear world; Threads would have the additional impact on my nervous heart of having been filmed in my hometown.

This climate affected me deeply; although my first love was literature I opted to study History and Politics at university. There I would meet others with similar anxieties. I remember in particular a friend who left his notebook in my room one day, open at a page on which he had doodled a mushroom cloud. We were in Boston, Massachusetts, in the summer of ’82. I can still recall his inscription beneath the picture: “I am afraid the world is going to blow up and I won’t see mom and J [name of his sister] again.” I felt uncomfortable reading his private reflection but took strange comfort from our shared fear.

This climate affected me deeply; although my first love was literature I opted to study History and Politics at university. There I would meet others with similar anxieties. I remember in particular a friend who left his notebook in my room one day, open at a page on which he had doodled a mushroom cloud. We were in Boston, Massachusetts, in the summer of ’82. I can still recall his inscription beneath the picture: “I am afraid the world is going to blow up and I won’t see mom and J [name of his sister] again.” I felt uncomfortable reading his private reflection but took strange comfort from our shared fear.

The bunker

The following summer the friend visited me in England. As well as spending time in London, where I was a student, I took him home to the Yorkshire coalfields where my Dad worked. The area would become the focus of fierce confrontations between the miners and Government as Thatcher embarked on a programme of pit closures the following year. In the summer of ’83, however, our concern was not yet with coal; our anxiety was still, predominantly, the risk of nuclear war. It must have been around this time that I had my first conversation with Dad about what we would do.

The following summer the friend visited me in England. As well as spending time in London, where I was a student, I took him home to the Yorkshire coalfields where my Dad worked. The area would become the focus of fierce confrontations between the miners and Government as Thatcher embarked on a programme of pit closures the following year. In the summer of ’83, however, our concern was not yet with coal; our anxiety was still, predominantly, the risk of nuclear war. It must have been around this time that I had my first conversation with Dad about what we would do.

Dad, what will we do if a nuclear bomb drops? I mean, I know what will happen – but what would we do? Straight afterwards I mean?

Well now our Elizabeth it’s funny you should ask me that. I’ve asked myself the same thing.

Dad’s answer surprised me. I hadn’t realised that grown-ups had these thoughts too but Dad, it seemed, had a plan. At the first sign there was something wrong, he said, I should get home as quickly as I could. Then we would go together to the colliery where he worked. We would go underground. The mine shaft was deep and the tunnels extensive. It would be the safest place to be in an attack. Dad had thought it through. People who didn’t work at the mine would head there too, he said. There would likely be a stampede. We would have to be quick to have a chance of getting down. People wouldn’t stand politely in line offering their tallies (the metal tags used to clock miners in and out) for admission.

Dad’s answer surprised me. I hadn’t realised that grown-ups had these thoughts too but Dad, it seemed, had a plan. At the first sign there was something wrong, he said, I should get home as quickly as I could. Then we would go together to the colliery where he worked. We would go underground. The mine shaft was deep and the tunnels extensive. It would be the safest place to be in an attack. Dad had thought it through. People who didn’t work at the mine would head there too, he said. There would likely be a stampede. We would have to be quick to have a chance of getting down. People wouldn’t stand politely in line offering their tallies (the metal tags used to clock miners in and out) for admission.

After this conversation we updated each other with our plans from time to time. I suggested that leaders would emerge; decisions would be made about who should get a place in the paddy trains. Maybe Dad would be seen as someone worth making space for; he was a Sparky so could be useful. I, meanwhile, didn’t have anything to offer. They’d need people with brains as well, Dad reassured me. And so I spent the rest of the decade making a note of the nearest mine (or tube station) and collecting literature on nuclear warfare.

After this conversation we updated each other with our plans from time to time. I suggested that leaders would emerge; decisions would be made about who should get a place in the paddy trains. Maybe Dad would be seen as someone worth making space for; he was a Sparky so could be useful. I, meanwhile, didn’t have anything to offer. They’d need people with brains as well, Dad reassured me. And so I spent the rest of the decade making a note of the nearest mine (or tube station) and collecting literature on nuclear warfare.

Anxiety, adolescence and autism

Looking back on those years it seems to me that what I, and other young people, suffered from was generalised anxiety. The perceived threat was constant but removed from our everyday lives; the idea of a finger on a button in some distant place, causing the release of something invisible but deadly, created free-floating worry. I don’t mean to suggest this is how I lived each day; I spent more time dancing than worrying, happily. But anxiety was certainly part of my youth.

Looking back on those years it seems to me that what I, and other young people, suffered from was generalised anxiety. The perceived threat was constant but removed from our everyday lives; the idea of a finger on a button in some distant place, causing the release of something invisible but deadly, created free-floating worry. I don’t mean to suggest this is how I lived each day; I spent more time dancing than worrying, happily. But anxiety was certainly part of my youth.

If adolescence is a time of idealism and questioning, and if young people are vulnerable to anxiety about the future, then presumably the current climate is as scary to young people today as the cold war was to me. Current threats may feel less abstract than nuclear war appeared to those of us who came of age in the ’80s but this doesn’t reduce the potential for anxiety. I’ve had some opportunity, as an adult, to witness the impact on teenagers of accounts of war. Poetry from WWI continues to be a mainstay of the school curriculum in England while literature which focuses on the experience of women and children is a popular approach to teaching young people about WWII (Ann Frank’s diaries for example). I have seen some young people break down when encountering these and other accounts.

If adolescence is a time of idealism and questioning, and if young people are vulnerable to anxiety about the future, then presumably the current climate is as scary to young people today as the cold war was to me. Current threats may feel less abstract than nuclear war appeared to those of us who came of age in the ’80s but this doesn’t reduce the potential for anxiety. I’ve had some opportunity, as an adult, to witness the impact on teenagers of accounts of war. Poetry from WWI continues to be a mainstay of the school curriculum in England while literature which focuses on the experience of women and children is a popular approach to teaching young people about WWII (Ann Frank’s diaries for example). I have seen some young people break down when encountering these and other accounts.

In my last post I raised the issue of how and what we tell autistic people about war. Dylan’s learning disability is significant enough to affect his ability to engage with the concept intellectually. As he is also lucky enough to live in a place where he doesn’t have direct experience of war, Dylan’s knowledge is limited to the few films he watches which include battle scenes (Lord of the Rings, for example, and Brave). Recently, during a meeting to discuss changes in Dylan’s behaviour, a psychologist suggested that Dylan may find it difficult to separate fantasy from reality. If he is watching a DVD in which a human is swallowed by a whale, she said, or a boy grows ears like a donkey, then Dylan may be anxious that these things could happen to him. Perhaps, she said, Dylan’s distress is caused by increased anxiety as he tries to make sense of the world through older eyes.

In my last post I raised the issue of how and what we tell autistic people about war. Dylan’s learning disability is significant enough to affect his ability to engage with the concept intellectually. As he is also lucky enough to live in a place where he doesn’t have direct experience of war, Dylan’s knowledge is limited to the few films he watches which include battle scenes (Lord of the Rings, for example, and Brave). Recently, during a meeting to discuss changes in Dylan’s behaviour, a psychologist suggested that Dylan may find it difficult to separate fantasy from reality. If he is watching a DVD in which a human is swallowed by a whale, she said, or a boy grows ears like a donkey, then Dylan may be anxious that these things could happen to him. Perhaps, she said, Dylan’s distress is caused by increased anxiety as he tries to make sense of the world through older eyes.

It was interesting and useful for me to hear this. Perhaps I should have realised before. Dylan may be autistic with a learning disability but he is probably still experiencing some of the anxiety which I felt at his age, albeit differently triggered. I had speculated for a while that certain story lines in his DVDs may be the cause of Dylan’s distress – separation narratives such as a baby dinosaur losing its mother for example – but having watched Dylan viewing his films in the last couple of weeks I think fighting makes him anxious too.

The attic

One of my recurring dreams is set in a post-apocalyptic world. Over the years it has changed in detail but the context is the same: I am wandering in a familiar city, trying to get to a place of safety. I suspect I am not alone in such imaginings; along with falling, being chased and railway stations it is, apparently, a fairly standard dream. One of the things which interests me, though, is how the narrative changed after I had children and especially since I became a carer.

One of my recurring dreams is set in a post-apocalyptic world. Over the years it has changed in detail but the context is the same: I am wandering in a familiar city, trying to get to a place of safety. I suspect I am not alone in such imaginings; along with falling, being chased and railway stations it is, apparently, a fairly standard dream. One of the things which interests me, though, is how the narrative changed after I had children and especially since I became a carer.

These days my war dream is likely to involve a desperate attempt to save one or both of my children from various dangers. These may be natural disasters which I must survive by physical strength or danger from an enemy who I must outwit. Often, the situation presents itself as challenging because of Dylan’s disability. So in one version of my dream, for example, we are in a hiding place which requires us to be silent. I assume the source for this is Ann Frank’s diary with its account of hiding in an attic room; occasionally I use an extract from her diaries with students and perhaps the discussion emerging from these sessions triggers my imagination. In my dream, however, what becomes horribly scary is my inability to ensure Dylan’s silence.

These days my war dream is likely to involve a desperate attempt to save one or both of my children from various dangers. These may be natural disasters which I must survive by physical strength or danger from an enemy who I must outwit. Often, the situation presents itself as challenging because of Dylan’s disability. So in one version of my dream, for example, we are in a hiding place which requires us to be silent. I assume the source for this is Ann Frank’s diary with its account of hiding in an attic room; occasionally I use an extract from her diaries with students and perhaps the discussion emerging from these sessions triggers my imagination. In my dream, however, what becomes horribly scary is my inability to ensure Dylan’s silence.

This fear of not being able to conceal ourselves because of Dylan’s disability is a narrative which resonates with that of other vulnerable groups during wartime. As well as my concealment dream I have conjured visions of pilgrimage, famine and siege, each of which presents particular challenges within the context of autism: being confined to the house, not being able to eat and having to walk somewhere unspecified would all be difficult for Dylan.

This fear of not being able to conceal ourselves because of Dylan’s disability is a narrative which resonates with that of other vulnerable groups during wartime. As well as my concealment dream I have conjured visions of pilgrimage, famine and siege, each of which presents particular challenges within the context of autism: being confined to the house, not being able to eat and having to walk somewhere unspecified would all be difficult for Dylan.

These narratives may emerge in dreams but I imagine they touch on a reality. If you are autistic a particular challenge of war, presumably, would be the breakdown of structure and routine. Meals would be an issue for someone like Dylan who eats only a limited range of foods in a specific colour. There would, of course, be no DVDs. That would be hard. No baths. No trains. No day centre. No going outside. While these examples may seem trivial from an everyday perspective, from an autistic perspective the loss of routine can represent a loss of self. For Dylan, routine is enabling and, I think, keeps anxiety at bay.

These narratives may emerge in dreams but I imagine they touch on a reality. If you are autistic a particular challenge of war, presumably, would be the breakdown of structure and routine. Meals would be an issue for someone like Dylan who eats only a limited range of foods in a specific colour. There would, of course, be no DVDs. That would be hard. No baths. No trains. No day centre. No going outside. While these examples may seem trivial from an everyday perspective, from an autistic perspective the loss of routine can represent a loss of self. For Dylan, routine is enabling and, I think, keeps anxiety at bay.

Actually, I find it very difficult to comprehend what would happen. I don’t know how someone autistic would survive a warzone. My dreams present me with these problems and unanswered questions again and again.

Where have all the autistic children gone?

And because of this I have made a point, over the years, of examining newsreel footage from war zones and scenes of natural disaster. Where are the autistic children I ask myself? They never seem to be in camera; the silent children waiting patiently in line for food rations, or sitting quietly in the corner of a makeshift shelter, do not remind me of my son. The mothers the reporters interview do not refer to the difficulty of managing with an autistic child to care for. I cannot believe that it is because autism doesn’t exist in these places. Are they lost or just out of camera? Where did they go, the autistic children?

A couple of weeks ago my attention was caught by a trailer advertising a radio drama, The Boy from Aleppo Who Painted The War, based on a novel of that title by Sumia Sukkar (Eyewear Publishing, 2013). The story follows the experience in war-torn Syria of Adam, a boy with Aspergers Syndrome. Given my longstanding curiosity about the absence of autistic children from media accounts of war, I listened with interest to this fictional representation. Perhaps it would provide an answer and an ending to my dreams?

In a future post I will review the radio production…

Images:

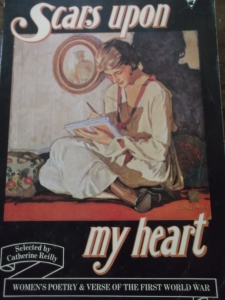

- The photograph of Soviet Submarine Classes was taken by me at Dungeness Lighthouse in Kent. I also took the photographs of an Orgreave miners’ tally; a Government information leaflet and an anthology of WWI poetry.

- The images for When the Wind Blows and the Threads DVD are from Wikipedia

- The image from Brave is via Pixar.Wikia.

- The images of mines are from the BBC (pit head) and miningartifacts.org (underground)

- Scenes from Threads are used in ‘The attic’ section of this post: these are from sheffieldhistory.co.uk except for the traffic warden who is via showroomworkstation.org.uk (Sheffield’s wonderful independent cinema).

- The image of the Sumia Sukkar novel is via Eyewear Publications.

I have been following your blog for a while now. I always find it very interesting and often very moving. You have great fortitude.

I too was born and grew up in Sheffield. My own youngest sister ( born in 1956) was very afraid of nuclear war. I remember her going through a stage when she would not let my mother out of her sight in case the bomb fell.

The Cuban Missile crisis of 1962 was a particularly anxious time for everyone who understood what was going on and even though my sister was only 6 then, something of the atmosphere must have communicated itself to her.

LikeLike

Hello Tom – thank you for following my Blog and for your kind words. So you are from Sheffield too! I was almost reassured to hear about your sister. I have sometimes wondered to what extent others experienced this anxiety. I’m a little younger than your sister, though the same generation. Like her I was too young to understand the Cuban Missile crisis at the time but I studied it at college and built it into my psyche I think. I was trying to recall when some of this faded – I suppose in the later Gorbachev days. Thank you for your comment – good to hear from you 🙂 Liz

LikeLike

Such an interesting and thoughtful post. I remember fearing a nuclear war and having many discussions with friends about how we’d survive and whether we’d want to still be alive. It must have had quite an impact on us psychologically. I remember the government information booklet ‘Protect and Survive’ which had instructions about how to build a shelter under a table. I can’t imagine how this was meant to be taken seriously.

LikeLike

Thank you! It’s interesting that you also experienced some of these feelings. The under the table advice is hilarious…perhaps someone somewhere is collecting such literature – it would make an interesting study I think, Liz

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Autism And War In Fiction: The Boy From Aleppo Who Painted The War by Sumia Sukkar | Living with Autism

Pingback: The Next Step | Living with Autism

Pingback: Lockdown: Creativity, Flexibility and Adjustment | Living with Autism